You’ve seen many market disruptions in your lifetime. Can you put this one in context as to the challenges and opportunities you think it presents for investors?

Ed Wachenheim: It’s difficult to judge the severity of this decline. As in most periods of extreme stress, we’re in unchartered waters and each decline is different. What’s causing a lot of the uncertainty for investors is that it’s difficult to analyze how secondary problems triggered by the health crisis and the resulting efforts at containment will impact business and consumer spending, unemployment and the broader economy. I could make a case that a recession will continue into 2021, and that the economy will bounce back strongly then because of deferred demand. Families that wanted to purchase a house, say, in the spring of 2020 will instead purchase it in the spring of 2021. But I don’t know, so I avoid investment decisions that require I do know things like that.

I have been through several sharp stock-market declines and economic crises before. Our approach is simple. We pay little attention to where particular stocks are priced at any given moment, and a lot of attention to the value of those stocks in a normal market. At all times we try to own companies that have strong balance sheets, high-quality businesses and very competent management. These companies should not only survive a crisis, but also may very well exit the crisis in an improved competitive position if weaker competitors face lasting impairments. That certainly was the case in multiple industries in the aftermath of the financial crisis.

Importantly, after every sharp decline in the stock market since WWII, the market has then fully recovered and then appreciated to higher levels. Sharp declines are nerve-racking, but they should not affect the long-term performance of a portfolio. I do not believe that our clients would be any wealthier today if the 2008-2009 financial crisis had not occurred. As Warren Buffett says, “If a business does well, the stock eventually follows.”

How would you say your strategy and approach “prepare” you for times like these?

EW: We can’t anticipate black-swan events and we generally don’t anticipate short-term economic developments such as moves in interest rates. In normal times, we don’t hold cash because we're usually able to find a sufficient number of attractive stocks to be fully invested.

We do, however, consider the longer-term risks in the economy and the relative valuation level of the stock market. Last year, for example, we became concerned about broad-based asset inflation and heightened political risks. Based on the metrics we use, the stock market was selling at a higher-than-normal level. We estimate that the “normal” earnings level for the S&P 500 is currently about 160. Over the past 50 or so years, the average price/earnings ratio on the S&P 500 has been about 16x. To us, then, a normal level for the S&P 500 is therefore around 2,560. When the index started trading materially above that level – it got as high as 3,400 in February – we started to become quite a bit more cautious.

We were also concerned that a long period of low interest rates had incentivized many investors and companies to over-leverage themselves and overpay for assets. And then there were the political concerns – with both our present government and the prospect that a socialistic administration might be elected in November. When we believe the longer-term risks are high, we set higher standards for new purchases and are quicker to sell stocks when they come closer to being fully valued.

That’s what happened last year, as we sold several holdings that had appreciated sharply and one whose balance sheet did not meet our tightened standards with respect to debt leverage. At the same time we were having difficulty finding any sufficiently attractive new ideas, so we built a substantial amount of cash – although never enough in hindsight. So while we cannot specifically prepare for a black-swan event, our discipline makes us more risk-averse when the stock market is selling at a high price and/or when we have other material intermediate- to long-term concerns.

Describe how you’ve been responding since the market cracked earlier this month.

EW: I have often seen intelligent and experienced investors lose control of their emotions and make ill-advised decisions during times of stress. My approach to combat that is pretty straightforward. For each of our holdings we try to be as dispassionate as we can be in reviewing why we owned something in the first place and then asking three basic questions: What really has changed? How have the changes affected the value of the investment? Am I sure that my appraisal of the changes is rational and is not being overly influenced by the immediacy and the severity of the current news?

In general, we select our portfolio companies based on the long-term attractiveness of their business models and their industries. We value them based on what we believe they can earn two to three years out in a normal economic environment if the expectations for positive change that we're counting on play out. For the normal valuation multiple we adjust up or down from the 16x long-term market P/E based on our assessment of the quality of the business and the long-term risks.

In the current situation, once it appeared that there was a high probability of an economic downturn – possibly a severe one – we also immediately reviewed the financial strength of each of our holdings – their balance sheets, their liquidity, and any possible demands on their cash during a period of stress. With respect to the long-term positive changes we're expecting on a company-by-company basis, these are unlikely to change during a difficult period, so we don’t tend to reassess our basic themes.

We have not been fast to buy or sell this month as the crisis has taken hold. As value investors we often own industrial and financial companies that tend to be more cyclical than the economy – many of which have fallen materially more than the market since mid-February – but this does not bother us because our focus is on the value of the company, not the momentary price of its shares.

It’s safe to say we’re researching a number of strong companies who will survive this and other adversities and whose shares might be undeservedly depressed. At the same time, conditions are changing so rapidly and those changes can effect intermediate-term values pretty significantly. We have a number of both present and prospective holdings in which we are considering transacting. I’m afraid I can’t discuss those yet.

We’re a bit surprised you weren’t earlier in adding to select existing positions.

EW: We typically hold 15 to 20 stocks in the portfolio. My philosophy has always been that if we hold fewer than 15 stocks, we’re taking on more risk of being wrong with one company than I’d like. If we own 30 to 40, experience tells me that roughly half would be my favorites and the rest would either have less upside potential or more risk. So rather than force myself to make that choice between less upside or more risk, I just limit the number holdings to my 15 to 20 favorites. Too often managers are willing to buy the stocks with more risk rather than give away upside, which I think can often offset whatever benefit they think they are getting from greater diversification.

To minimize risk and attain diversity, we set a limit on the maximum percentage of the portfolio any stock or industry can represent. When we like a stock and its industry, we usually purchase up to the maximum percentage. Thus, should the prices of stocks generally decline, we usually do not have room to add to our existing holdings – they were already at the maximum percentage of the portfolio.

ON POSITIONING TODAY:

This is really a time to seek quality. Both quality and cash are the queens and kings at the moment.

In terms of our overall level of risk aversion, obviously with shares selling at lower prices many stocks are priced at levels where there appears to be substantial downside protection. In that respect our risk aversion is somewhat less, but we remain concerned about secondary effects of the sharp economic downturn. How many leveraged private equity investments, commercial real estate investments, high-yield investments, leveraged loans, etc. will cause economic losses? This is really a time to seek quality. Both quality and cash are the queens and kings at the moment.

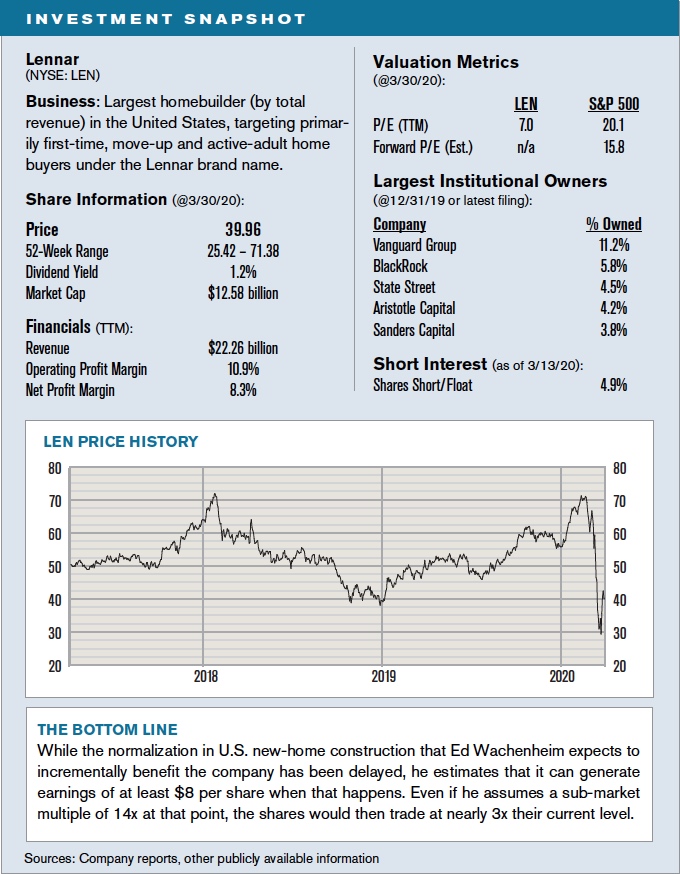

Let’s talk about a few ideas from your existing portfolio that you believe with a long-enough time horizon will prove attractive. Please update your investment case for homebuilder Lennar [LEN].

EW: The homebuilding industry in the U.S. has changed from being asset heavy to asset light as builders have changed their strategies from owning large amounts of land to owning as little land as feasible. As a result of this change, homebuilders like Lennar have much stronger balance sheets, free cash flows and returns on equity. It simply is a different business today than it was ten or twenty years ago. In addition to that, because of efficiencies of scale the largest builders have economic advantages over smaller ones, which is leading to further consolidation in the industry. The strong are becoming stronger and are enjoying higher margins due to scale and reduced competition.

While the short-term outlook is clearly highly uncertain, we believe demand for new homes in the U.S. should be strong in the coming years, not only to meet the needs of our growing population, but also because we have underbuilt new housing during the last dozen years, leading to a shortage of homes. The demand for new homes over the longer term is more predictable, simply because families have to live somewhere.

In our opinion Lennar is particularly well positioned and well managed. It’s the second-largest builder in terms of units and the largest in terms of dollar revenues. In a market where scale is increasingly important and provides competitive advantage, improving demand should incrementally benefit it. Demand for new houses was very strong in late 2019 and going into 2020 and we believe that demand will come back at least over the next few years, maybe even more so given potentially lower mortgage rates.

The bear case would argue that some of the trends that have contributed to underbuilding – later marriage, more multi-generational families living together, increased demand for urban living, etc. – will prove more permanent than temporary. What makes you skeptical of those arguments?

EW: Yes, later marriage and multi-generational living has likely played a part in the slowness of the housing market’s recovery. But the multi-generational delay can only go so far before it no longer is a factor, and many children lived with their parents after the financial crisis out of financial need, not out of choice. Most women want to get married while they are young enough to bear children, so that also doesn’t strike me as a permanent factor.

Regarding urban living, we believe that most families still will want to live in their own home in areas where the schools are better than typical urban schools and where there is a backyard for children to play in. We still believe most American families prefer the ownership of a home – and the recent housing numbers, through the end of last year at least, were bearing that out.

The shares at a recent $40 are down around 35% since the beginning of March. It’s hard to think about “normal” at a time like this, but what kind of upside could we see if we get back to that and the coronavirus and its aftermath go away?

EW: Before the Covid-19 crisis broke, we were estimating that Lennar would earn about $6.40 in its current fiscal year [ending in November], $7.00-plus in fiscal 2021 and $8.00-plus in fiscal 2022. The timing of that is now obviously up in the air, but earnings-per-share gains should eventually come from some continued growth in demand for new houses, some market-share gains, some higher margins as the company employs new initiatives it has developed – such as dynamic pricing – and from share repurchases. While the shares of NVR, a competing builder that has been asset light for some time, have historically sold at 16-18x earnings, I’ve been valuing Lennar at 14x my earnings estimates, which may prove conservative. Bottom line, even using that conservative valuation, I rarely have found a more compelling investment opportunity.

I should add that homebuilders typically generate cash during periods of demand decline. They receive cash when a home sale closes, so when there are more closings than starts, balance-sheet cash increases. Also important here from a downside perspective is that Lennar’s hard book value currently is somewhat in excess of $50 per share, and if we’re right about our long-term outlook, that book value should increase at a healthy 10%-plus annual rate over the next several years. The risk to that would be if the company repurchased large amounts of stock at big premiums to book value, which we don’t at all expect to be the case.

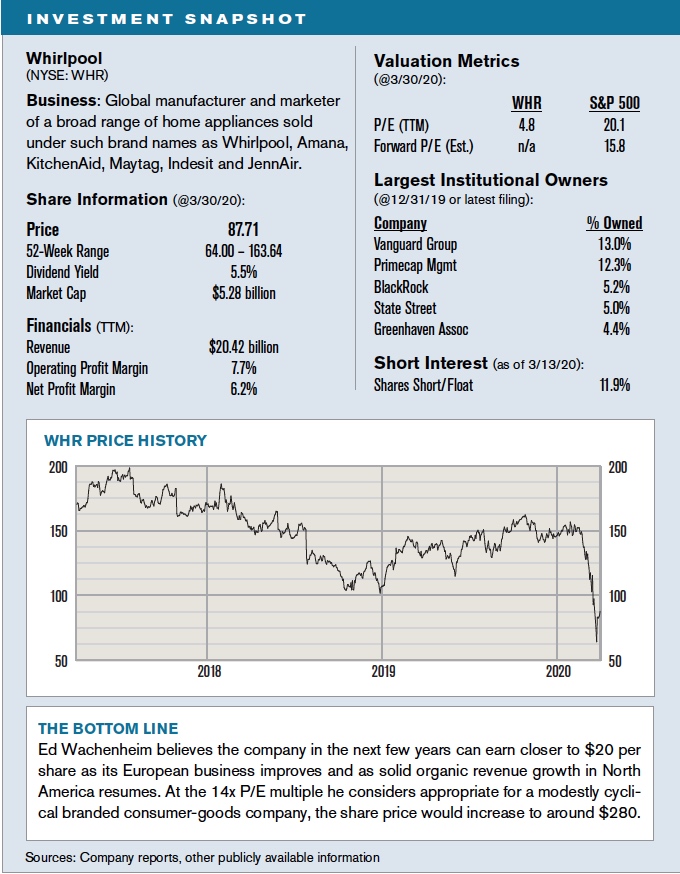

Turning to more of an industrial idea, describe the investment opportunity you see in appliance-maker Whirlpool [WHR].

EW: Whirlpool is the leading large-appliance manufacturer in North America – by a not inconsiderable margin – with brands including Whirlpool, Maytag, JennAir and KitchenAid. It has large-scale and highly efficient factories and is the low-cost producer in North America, also by a fairly good margin. We’re consistently impressed with management and expect large projected cash flows to lead to smart capital allocation, including significant share repurchases in the next several years.

One thing weighing on Whirlpool’s performance has been difficulty in Europe. The company several years ago acquired Italy’s Indesit, which it saw as very important to building the scale it lacked in Europe. It also saw the opportunity to materially lower costs there by combining manufacturing platforms and facilities. There have been a number of problems along the way, however, including supply-chain and production issues that resulted in the company not being able to meet demand. That resulted in a loss of retail floor space and European sales declined. We believe a lot of those issues have been solved and the company has been regaining some of its lost share. As this continues, especially if the demand picture improves from a depressed base, profits from Europe should rebound.

While Europe is important, North America will be the primary driver of Whirlpool's success. One thing we like about the business is that the bulk of demand isn’t that discretionary because it results from the replacement of aged and broken appliances. When an older washing machine, refrigerator or stove breaks down, you need a new one. At the same time, we also see latent demand for the company’s industry-leading brands as new-home demand and supply increase. While it’s not a long-term reason to own the stock, an additional defensive aspect of the business is that more time spent at home in coming weeks and months could result in increased demand for certain of the company’s products. Management has indicated, for example, that demand for freezers has been particularly strong as many households have been stocking up on food.

What potential upside could you eventually see in the stock, now trading at around $88, 45% off its 52-week high?

EW: The company earned around $16 per share in 2019 and we project that with modest organic revenue growth, a turnaround in Europe and some benefits from operating leverage and from share repurchases, that it could earn close to $20 per share in a few years. So the shares currently trade at less than 4.5x what we think the company can earn in a more normal environment. If in fact the shares traded at the 14x or so multiple we’d consider appropriate for a high-quality branded consumer-goods company that is modestly cyclical, the stock could be at closer to $280 two to three years from now.

We’ve spoken in the past about the long-term potential you see in Goldman Sachs [GS]. Please update your thinking on it.

EW: Goldman Sachs is the leading investment banker in the world. Its management team is consistently capable, ambitious and deep. It continues to attract the best graduates. Maybe these types of things don’t lend themselves to rigorous financial analysis, but in this type of business all of that is still extremely important.

After the financial crisis, Goldman and large financial firms like it have been highly regulated and have been forced to maintain sufficient capital for extremely stressed conditions, including a recession with 10% unemployment and a very weak stock market. Even with those tighter restrictions, the company has had sufficient capital to pay increasing dividends to shareholders and to repurchase large quantities of its shares. Its balance sheet is strong and full of liquidity. That is a great asset in the hands of capable management.

You typically look for important positive changes in a business that can drive long-term shareholder value growth. What are the key secular or company-specific changes you see in that regard here?

EW: There are two items to highlight with respect to Goldman. One, the company we believe has a credible plan – from things like cost reductions, the redeployment of capital from market-making to more attractive business lines, and from share repurchases – to increase its return on tangible common equity to around 14% in the next few years. If that happens it would likely result in a significant reappraisal of the share valuation.

The other change is more general. This in my opinion is a representative example of a value stock trading at a particularly depressed price. On trailing earnings the P/E is less than 8x. Eventually the true intrinsic value of companies like this will be reflected in the price of their shares, a change I will celebrate with a nice bottle of Champagne.

With its shares trading at just under $160 – down about 20% this month – how are you looking at upside?

EW: Prior to the COVID-19 crisis Goldman was earning better than $20 per share, and if management hits its return-on-equity goals the company’s earnings power should be closer to $30 per share. We believe the stock would be worth at least 12x earnings if all that comes to pass, which would result in a share price of $360. That would also be justified by hard book value per share, which from around $205 today could reach $250 in a few years. A company of this quality should actually trade at a large premium to its hard book value.

In one of our conversations years ago you expressed concern that “as I become older and more financially secure I will become too risk averse.” Is that still something on your mind?

EW: Because I am cognizant of the risk that I could potentially become too risk averse, it’s very important that I maintain the same investment discipline and criteria that I’ve used since I was younger and more hungry. It often takes conscious effort, but I believe I’ve been successful in doing that.

You’ve often spoken about the need to master your emotions to be successful as an investor. Now 60 years into your investment career, any final advice for others on how to pull that off when markets behave as they have recently?

EW: Obviously, the current environment is stressful, but more because of the health risks than the market. In mid-March, my wife and I decided to avoid all social contact with everyone except those who themselves were avoiding all social contact. With respect to the market, surely it has been nerve-racking, but I’ve been through many down markets before and my muscle memory prevents me from becoming emotional. I somehow instinctively know that we will come out of this and the market will recover and then go on to new heights.

ON KEEPING CALM:

I somehow instinctively know that we will come out of this and the market will recover and go on to new heights.

When that happens, I obviously don’t know, but it should make little difference to a long-term investor. As I described earlier, our clients likely would be no wealthier today if the October 18, 1987 collapse had not occurred, or if the bear market of 2000-2002 had not occurred, or if the financial crisis had not occurred. And there have been dozens of other times when problems loomed large at the moment, but have since faded from memory. With that grounding, it’s not that difficult for me to keep emotions out of my decision making.