Hennessy David Ellison Ryan Kelley PayPal PYPL JPMorgan Chase JPM Opus OPB Union UBSH Independent INDB LendingClub On Deck GreenSky Zillow Wells Fargo WFC Goldman Sachs Ozark Ayden

After more than 30 years investing almost exclusively in financial stocks, can you recap some of the biggest changes in your world that bring us up to today?

David Ellison: When I joined Fidelity in 1983 the fed-funds rate at which banks lent reserves to each other overnight was around 18%. Rates falling from there was a great elixir for many years, allowing companies to repair balance sheets and then bringing about an explosion in the use of debt and what I call the financialization of global economies as international trade took off and money moved more quickly and in greater volumes around the world.

At some point, the decline in interest rates became a negative. Money got too easy and at the same time low rates started to take away margin at financial institutions. That caused a lot of things to happen, one of which was institutions taking on more risk to make a buck. Mortgage loans went from requiring 20% down and full documentation to no money down and no documentation. There were a number of causes of the financial crisis, but that dynamic was a contributor.

I don't want to say we have too much financial-industry regulation now – we clearly had too little in 2007 – but the increased regulatory constraints on the sector have taken energy out of the space. There isn't the capitalistic élan there once was. Previously active and profitable parts of the market like mortgage lending and student loans are largely controlled by the government. The highway has gone from 10 lanes to three, and that's resulted in banks having less flexibility and looking more the same, with the same products, the same lending books, the same cost of funds and the same yield on assets.

ON REGULATION:

Increased regulatory constraints have taken energy out of the space. There isn't the same capitalistic élan.

What I'm describing is safer for the economy as a whole, but it makes my job as a portfolio manager more difficult. How do you invest when there are fewer discernible differences among companies? And when you find discernible differences, in an increasingly indexed world those differences seem to matter less – in the short run at least. After the U.S. presidential election, everything in the sector was a buy. In the last couple of months, everything has been a sell. That makes it harder to create differentiation between your fund and the sector and market as a whole. Of course, everyone's in the same boat.

Let's talk about how you try to differentiate yourself. Describe the type of bank, for example, that attracts your interest today.

Ryan Kelley: The real value in a bank, especially the smaller it gets, is in the strength of its ability to consistently raise and maintain a low-cost deposit base. That's always been more about geography and relationships and you can still find banks that have it.

A good example we own in our small-cap fund is Independent Bank Corp. [INDB], which is headquartered just south of Boston and operates in compact markets with strong market shares. That doesn't mean big-bank competition isn't there, in fact we like that banks like Bank of America are big in INDB's markets because they generally aren't going to be as competitive for deposits.

Because of strong relationships with both consumer and commercial customers, nearly one-third of INDB's deposits are in non-interest-bearing accounts. Its all-in cost of liabilities is between 50 and 55 basis points, where 80 to 100 would be more normal. From there, good things can happen. The credit culture is conservative and they've done a good job in making accretive bolt-on acquisitions. Management is focused on growing tangible book value and we believe they can continue to do that at a 10% or so annual rate. It may be a bit boring, but it's the type of thing we're happy to own today.

DE: This is an example of a company that understands that banking is a get-rich-slow business. It's about compounding tangible book value over time. Independent Bank operates in markets and with advantages that should allow it to do reasonably well in good times and reasonably well in bad times. They should do OK when interest rates are going up or interest rates are going down. It's not quite as simple as "It's a Wonderful Life," but there's less to worry about, which is a very good thing.

You mention the economy and interest rates. Has investing in financials become much more about handicapping those types of things than it used to be?

DE: There's no question. Those things do and will always matter, but I'd say one characteristic of companies we want to own would be that we think they will matter less. I really don't want to have to have a view on the yield curve or GDP growth to find a stock attractive. That's a very humbling thing to try to do.

One important step we've taken in that regard, primarily in the large-cap fund, is to build exposure to companies in the electronic-payments space, from big long-term winners like Visa [V] and Mastercard [MA] to rising competitors like PayPal [PYPL]. This is a giant, secular-growth market where margins for the best-positioned companies can be very high. With an appropriately long-term view, in these companies I don't really have to worry about interest rates going up, or the inversion of the yield curve, or the extent of Fed regulatory oversight, or the health of the economy and how that impacts loan growth and credit quality. They're long-term plays on the digitalization of the global industry and help us diversify away from what for now is a reactionary market around deposit takers and lenders.

We don't see much in the way of "fintech" companies in your portfolios. Why?

DE: I'd actually say that companies in the payments space like Visa and Mastercard are the more-pure fintech plays. They're outside the world of funding sources, loan volumes and credit quality.

What more often gets called fintech today are companies like LendingClub [LC], On Deck Capital [ONDK] or GreenSky [GSKY]. Their business models revolve around making loans, but the promise is that they have this special sauce based on technological innovation that will allow them to make those loans more efficiently, safely and profitably than everybody else. I've been hearing about secret-sauce lending strategies since the 1980s. To me that's not fintech, that's just another way of saying we have this proprietary model, we're special and smart, give us a big multiple. In my experience, that generally hasn't work out well at all.

There's also with these newer companies a greater risk of overreaching. We used to own Zillow [Z] because it was a real estate brokerage for the new economy. Brokers we spoke with told us that most house hunters, before contacting a broker, would start their search on Zillow to get a sense of available inventory and what houses were worth. That gave the company a highly attractive platform that took share from competing options and that it was able to monetize in a high-margin way.

ON WELLS FARGO:

It's all too bad, but that's what can happen when companies forget that the customer should come first.

Then management made what we consider a critical strategic error by deciding they should get into the businesses of flipping homes and offering loans. They are allocating capital away from a core business that was valued in the stock market at 30x earnings, to invest in risky, capital-intensive businesses that are more likely to get a 10x multiple. Since making the announcement of the new direction in April 2018, the shares are down around 40%.

Turning to one-time stalwarts in your world that have also disappointed, what's your current take on Wells Fargo [WFC]?

DE: Wells was considered one of the best operators in the industry, with historically good behavior, historically good credit quality and historically good returns. However it happened, it appears the company's corporate culture got polluted with an ethic of employees in a variety of ways putting their own interests ahead of just doing what was right for customers. They're still trying to work their way out of all the problems that has caused.

How optimistic are you they can do it?

DE: We still own a small stake in Wells, but in retrospect I should have sold a lot more when the bad news first started to come out.

When I started in the business, Fifth Third Bancorp [FITB] was considered the crème de la crème of regional banks, in terms of performance, management acumen and future potential. At this point I don't even know how exactly they lost it, but for a very long time now it's been considered nothing more than a middling bank with a middling valuation. There's a real risk that's where Wells is going. From an investment standpoint, it's lost its cachet. It's also lost its esprit de corps – small banks we talk to in Wells Fargo's markets tell us that's where most of the resumes they get come from. It's all too bad, but that's what can happen when companies forget that the customer should come first.

Goldman Sachs [GS] is another portfolio company of yours with some reputational issues to deal with. Do you consider its situation differently than Wells Fargo's?

DE: The cachet with Goldman, even with the Malaysia issues up to this point, is arguably still more intact. The stock certainly doesn't seem expensive. For me though, the question with the company today is what exactly is it? Is it a trading firm, and what is that worth? Is it an investment bank, and what is that worth? Maybe new management will pull it all together in a more compelling way, but right now for me it's a mush of disparate stuff without a definitive or clear view.

One reason you outperformed through the financial crisis was by backing off relatively early on bank stocks when you saw credit-quality metrics start to deteriorate. How would you characterize the credit quality today of your portfolio companies?

RK: To give some industry data, non-performing assets on bank balance sheets that were almost 3% of total assets right after the crisis are at 70 basis points today. Through September of this year the industry chargeoff-to-loan ratio has been running at minimum levels, around 45 basis points. The ratio has been below 50 basis points for five years, which is the best run of performance we've seen over the last 27 years. Following the crisis in 2010, chargeoffs to loans were around 2.7%.

DE: There have been some hiccups here and there, but bank lending standards have remained high and the level of non-performing loans is very low. Margins have moved up with rates and profit margins overall are high relative to history, as are returns on assets and returns on equity.

That said, the Fed is raising rates and reducing liquidity. Deposit costs are moving up. Loan growth is OK, but not great. Pricing is more difficult than it was. That's made the environment less positive than it was, and share prices reflect that.

When it comes to bank stocks, I think the ghost of 2008 is going to be with us for a long time. By that I mean when we see non-performers tick up, the market isn't going to wait around to sell. Look at Bank OZK [OZK], which until recently was known as Bank of the Ozarks. It maybe got a bit ahead itself, had some loans recently go bad and the stock just got killed. [Note: As high as $53.70 in March, Bank OZK shares recently traded at $22.60.] In big banks and small, if credit-quality issues come up investors are very likely to shoot first and ask questions later.

You described earlier your top-down interest in payments processors. Explain the more detailed investment case for PayPal.

DE: PayPal largely grew up as part of eBay to become a major player in vendor payments processing before it was spun off as an independent company in 2015. It has continued to broaden its business, including in peer-to-peer money transfer with the acquisition of Venmo in 2013, and today it's an entrenched competitor with around 255 million active accounts, a number that's growing 15% per year and driving 25% annual growth in payments processed. That's a huge head start in an industry with barriers to entry due to scale, regulation and the increasing complexity of cyber security. There are only a handful of significant competitors that are well positioned to capitalize on the industry's tremendous growth prospects.

We've owned the stock for three years and part of our original thesis was that it was a prime acquisition candidate for large banks or technology companies. While that's not critical to our case, it's still true. Facebook, for example, has an opportunity to enter the payments space in similar fashion to Tencent, which leveraged its social-media platform to create what is now China's second-largest mobile-payments business. Facebook has 2.6 billion users – if it integrates payment functionality into its messaging platform or adds commerce functionality to Instagram, it could be a source of significant revenue. PayPal with its scale would be an ideal partner to tackle that initiative.

Are you concerned by eBay's announcement earlier this year that it's taking its payments-processing business elsewhere?

RK: The deal is with Adyen [Amsterdam: ADYEN], a Dutch payments solution that will be integrated directly into eBay's platform, as opposed to customers going to PayPal's third-party site to complete purchases. The transition will be gradual, and eBay customers can still use PayPal until 2023. While eBay's share of PayPal volume has recently been running at around 13% of the total, that number continues to come down as PayPal successfully attracts new business. We also suspect eBay is a low-margin customer because of the prior affiliation. In any event, we think this news is well understood by the market and that the orderly and deliberate nature of the transition should minimize any earnings hiccups.

What's far more important to our investment thesis is Venmo, which reported 78% transaction volume growth in the third quarter as it becomes increasingly popular with millennials. Much of Venmo's service today is free, which leads some in the investment community to question its ability to be monetized. I would characterize that as a nice problem to have, given the rapid growth in consumer engagement. There's already some progress on that front, as the percentage of Venmo's users who have paid it for some service increased from 13% in May to 24% at the end of September. And in October, Venmo raised fees for instant bank transfers from 25 cents to 1% of the transaction value. We'll likely get a sense of the impact from that change when the company reports earnings in late January.

At $83.25, PayPal's shares are down 11% from their September highs. How are you looking at upside from here?

DE: The shares at around 29x forward earnings estimates are not objectively cheap, but we're willing to pay more to own a leader in a part of the financial services industry that isn't so much impacted by earnings-multiple depressants like the interest-rate and credit cycles. We think the multiple today accurately reflects the company's potential and if there were to be any multiple contraction, there's a good chance it would be offset by Venmo's significant untapped earnings potential. If we're right, we believe shareholder returns should approximate the company's earnings growth rate, which we estimate at around 20% for the next several years.

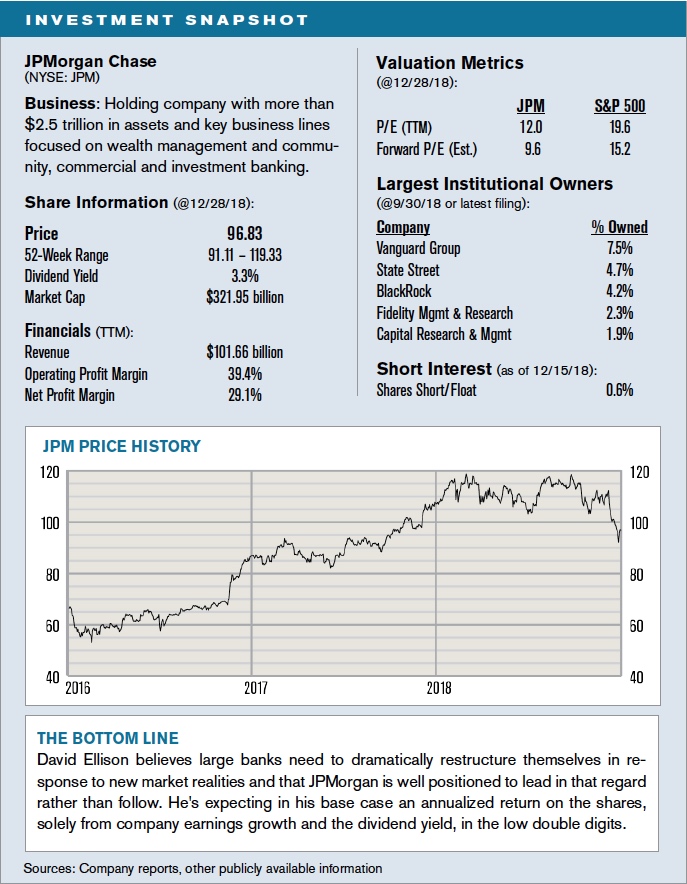

Given the structural challenges you see for big banks, what's your thesis today for a holding like JPMorgan Chase [JPM]?

DE: Our view is that for banks like this to thrive in this new environment they should significantly restructure their businesses. They need to get leaner by reducing bloated labor and real estate costs, including by closing branches that aren't essential in a world of digital banking. They need to deemphasize businesses like trading, brokerage and passive investment products where prices are racing towards zero. They need to deemphasize investment banking, which plays a less important role for new-economy, capital-light businesses. And they need to adjust their balance sheets that have been built on a 30-year bull market in bonds, fully preparing for flat or rising rates.

For management teams that recognize all this, we think there's a huge opportunity over the next decade for them to increase efficiency, lower costs and drive earnings growth, regardless of the rate of loan growth or the level of interest rates. If they construct their balance sheets with less risk and move more toward fee-based businesses, earnings quality and stability should also improve, which we believe will eventually result in higher valuations.

We think JPMorgan is the industry's gold standard, with better management, better returns, and greater wherewithal to evolve. In addition to upside from the restructuring we consider necessary, we think the investments they're making in true fintech, which depress earnings power today, will enhance it going forward. Jamie Dimon said in his 2017 shareholder letter that the company has nearly 50,000 employees in technology and is investing in a wide variety of areas, including artificial intelligence, machine learning and cloud infrastructure in order to enhance risk management, underwriting and efficiency. To give one example, the company in 2017 acquired WePay, which provides payments software for platforms like the crowdfunding website GoFundMe. Now JPMorgan is targeting its own four million small-business clients to increase distribution of WePay software. In general, this is not a company acting as if it yearns for the good old days.

At around $97, the stock is down 18% in the past three months. How do you see things playing out to shareholders' benefit from here?

DE: The stock trades in line with peers at less than 10x forward earnings. That's a more than 30% discount to the historical earnings multiple for large-cap banks, and also a 30% discount to where banks have typically traded relative to the earnings multiple of the S&P 500. Banks today are one of the cheapest sectors in the market, with clearly negative investor sentiment.

Looking through all that, we estimate that JPMorgan can generate earnings growth in the high single digits, which with the 3.3% dividend yield would provide a base-case return in the low double digits. Multiples could continue to contract, but ultimately we believe they have more potential to rise from here than to fall. If management successfully shifts the business mix as we believe it can, we think we'll benefit from multiple expansion on top of our base-case return.

What put southern California's Opus Bank [OPB] on your radar screen?

RK: We spoke earlier about looking for small caps with strong deposit franchises in attractive markets, but we also look for companies with discounted shares because of credit issues that we think can be resolved. Opus Bank falls in the latter category. It was founded in 2010 when Elliott Management, Fortress Investment and Starwood Capital provided funding to recapitalize what was then called Bay Cities National Bank. Now named Opus Bank, the company has about $7 billion of assets funded by $6 billion of deposits and operates primarily through offices in southern California and Seattle. These are high-tech, high-growth areas that provide a nice demand backdrop for a bank focused on commercial lending and also providing advisory services for capital financings and mergers and acquisitions.

Opus's share price has halved in the last three years following large loan charge-offs in an otherwise benign industry credit environment. Adding to the pain, net interest margin has contracted as management has pivoted away from higher-risk, higher-rate loans.

What's behind the credit problems?

RK: The trouble mostly stems from what they refer to as enterprise-value loans made to technology companies that weren't start-ups, but weren't fully established businesses either. These were companies taking advantage of low rates on loans rather than additional rounds of venture capital, but cash burn caught up to some of them in the bank's loan book.

After making significant initial progress in working through the enterprise-loan problems, the market has become concerned that charge-offs on such loans for Opus have ticked up again in 2018. While that's not ideal, we think the market has overreacted to this latest round of issues. The company's level of non-performing loans is more than fully reserved by its allowance for loan losses. By our calculations, even if the entire portfolio of enterprise loans was charged off, the stock would still trade at a discount to peers on tangible book value.

How are you looking at valuation today with the shares trading at around $19.50?

RK: Compared to an average of 1.6x tangible book and a forward earnings multiple of 13x for the small-cap bank universe, Opus trades for around 1x tangible book and 12.7x forward earnings. More importantly, given that there are three large investors who still collectively own around 35% of the outstanding shares and are likely to want to exit through a sale, small-bank acquisition multiples have lately been averaging about 2x tangible book. Depending on the amount of charge-offs ultimately required to clean up the balance sheet, we think a sale of the company could happen at a 50% or higher premium over the current share price.

Turning to another small-cap bank, why are you high on the prospects for Virginia's Union Bankshares [UBSH]?

DE: The company has $13 billion in assets and about 150 offices mostly in Virginia, but also reaching markets to the south in North Carolina and to the north in Maryland. We like these markets because there are a lot of small businesses and, owing to a relatively conservative culture, swings in the values of residential and commercial real estate tend to be relatively muted. The traditional nature also carries over to consumer preferences for keeping deposits at branches, which helps insulate Union from Internet-banking competitors and helps keep its funding costs low. These are important considerations for us; we look at the end markets as much as we look at the company when determining which banks to own. One advantage of having followed the industry for so long is that I've seen over time the markets that are prone to insanity and those that aren't.

The company has been fairly acquisitive over the past five years. We take it you see that as a positive.

RK: We do in this case. Union just over a year ago acquired Xenith Bankshares, with $4 billion of assets, and in October it announced a deal to buy Access National Corp., with $3 billion in assets. Buying Xenith we think substantially completes the company's Virginia franchise, while the Access National deal gives it a much stronger footprint in the Washington, D.C. metropolitan area. They paid 17x earnings for Xenith and 20x earnings for Access National, both discounts to the 24x average acquisition multiple paid in the industry in 2018.

The ultimate value of consolidation is from more market control translating into better pricing on loans and from higher deposit density translating into lower funding costs. Scale, of course, also improves expense ratios. All of this leads to a more predictable stream of earnings. As Union has successfully integrated acquisitions, its operating results have improved. Its net interest margin of 3.8%, for example, is significantly better than peers.

How do you assess Union's credit quality?

DE: Acquisitions can make the asset side of the balance sheet look messy. Union has roughly $330 million of criticized loans – generally those classified as doubtful or otherwise substandard – out of a $9.3 billion loan portfolio. That's relatively high compared to peers, but we think much of that discrepancy is due to conservative accounting on acquired loans. The marks negate the need for reserves, so while we believe the company's loan-loss allowance is appropriate, it can optically appear inadequate. In digging through the growth in loans, the mix and size of loans and the nature and risk profile of the loans, we're quite comfortable with the quality of Union's loan portfolio.

How cheap do you consider the shares at today's price of around $28?

RK: The shares trade for 10x forward earnings, excluding the acquisition of Access National that we expect to be as much as 5% accretive. That's a fairly steep discount to the 13x peer-group average. Our premise is that as they successfully integrate the recent acquisitions in coming quarters and as the loan quality proves better than what seems to be expected, the shares should eventually command – maybe even as a result of Union itself being acquired –a multiple at least in line with the current peer average. Were that to happen, we'd have a very satisfactory return.

Many value investors in the difficult market of late seem energized by seeing increased opportunities. We don't sense that from you to any great degree. Why not?

DE: Fundamentally, the companies we follow are doing quite well, and valuations in a number of cases have gotten extremely low. But I wouldn't say I'm having fun yet. I always say that you make money as an investor in this industry when fundamentals go from ugly to OK, from OK to good, and from good to great.

At the moment the fundamentals are pretty great, so I find myself wanting for something to actually go wrong that companies and stocks can come back from. Or maybe the environment in the sector just slowly deteriorates for a period of time and then we can expect things to get better from there. Honestly, the sooner something really goes wrong the better it will be for us in terms of looking for investment opportunities.

This year has been like a football game that started when it was 60 degrees and sunny and now in the fourth quarter it's 30 degrees and snowing. As my sister likes to say, "Deal with it." That's what we're trying to do.