Rajiv Jain James Anders Brian Kersmanc Sudarshan Murthy GQG CK Infrastructure Heineken HEIA KBC Infosys INFY Intercontinental Exchange ICE Vontobel HDFC HDB Mastercard Visa Tokio Marine Fortis Bankinter BBVA Rolls Royce Safran Valeant General Electric GE Facebook FB Tencent Hutchison

Like all successful investors, you hold some basic investment precepts quite dear. Please start off by summarizing a few of the most important ones.

Rajiv Jain: First of all, I don't feel I have any information edge as an investor. My track record has been built on buying large, liquid names in a relatively concentrated fashion, and I can't claim an information edge on something like Alphabet or Facebook. I have never met Mark Zuckerberg and I don't think he's waiting to meet me either.

To me it's about looking for businesses that can grow earnings at, say, 8-10% per year, with high-enough competitive barriers to entry that looking five years out we can reasonably expect the multiple to stay constant and we can harvest the underlying earnings growth and the dividend yield for our investors. I'm not trying to find some unique situation nobody has ever heard of, or a microcap that is going to be the next Microsoft. It's all about business sustainability and compounding.

I'm also very aware that everything we do is a working hypothesis and from there it's about reacting to data points. We don't have to be right in precise fashion about where the business is heading, but we do have to understand the context of the situation, make judgements that are directionally correct and – this is important – with a fully open mind continue to update our working hypothesis as the situation changes. It's human nature to anchor on prior conclusions and look for reasons to support your original thesis. I've tried to build a team and a process where that's less likely to happen.

You don't have to get it 90% right in investing. You can have a very good return with a much lower hit rate as long as you don't lose too much money when you're wrong and you make enough when you're right. Small losses along with big winners is the best way to compound over time – the reverse of that is a killer!

Does your variant perception tend to be more around the growth rates you expect or the sustainability of that growth?

RJ: It might be on the rate of growth, but most of the time it's sustainability. Most sell-side models go out a couple of years and then assume some sort of step-function down in growth or a terminal growth rate of some kind. Doing that might overly discount growth prospects that are more than a couple years out.

Let me give you an example, India's HDFC Bank [HDB]. When I first started buying the stock years ago it traded expensively for a bank, but I thought the context around its business, the sustainability of its growth potential and the quality of its management made it highly attractive.

The Indian banking system was nationalized in the early 1970s, but the government started giving out private banking licenses again in the early 1990s. HDFC got one of the early ones and went about building a modern banking franchise that we thought had clear and sustainable advantages over government-owned legacy competitors. They also set themselves apart from other new private-sector banks by specializing in key areas where they wanted to lead and expected to make excellent profits, rather than just pursuing a land-grab strategy like the others.

At the same time we thought HDFC would take market share, the market itself was massively underpenetrated and likely to grow overall at a mid- to upper-teens rate for an extended period of time. In this context paying a 20x multiple for HDFC versus 10x or so for the typical European bank was not at all expensive.

This particular thesis, by the way, is still intact. After a long run this is now a $90 billion-plus assets bank, but it has only a roughly 6.5% market share in a still significantly underpenetrated market. I've cut back and added to the position over time, but more recently have been a buyer as the competitive context has shifted more into HDFC's favor. The 70% of the banking system now controlled by the Indian government is undercapitalized and unable to lend. Many of the private-sector banks are distracted with sorting out issues created by substandard lending practices. That puts HDFC, with its strong balance sheet, in an excellent position to accelerate its own growth beyond what we believe the market is pricing in. [Note: HDFC's U.S. ADRs currently trade at $103, 20x consensus March 2020 EPS estimates.]

Your portfolios include both expected "compounder" names like Visa [V] and Mastercard [MA] as well as less-expected ones like Tokio Marine [Tokyo: 8766] and Fortis [Toronto: FTS]. Describe how those latter types of companies fit.

RJ: As I said, it's all about compounding, which can happen in a broad range of companies and industries. Tokio Marine is the largest and best operator in a Japanese property/casualty insurance industry that has historically been one of the best capitalized in the world. It has operated for a long time with a 90% or so combined ratio, generates low-double-digit ROEs, pays a 3.5% dividend and has started to use excess capital to buy back stock. Even with all that, the stock trades at 10x earnings and right around book value. With the capital return, we think we can compound our money in the low double digits over a five-year horizon, almost irrespective of what happens in the world. If we can do that over and over again in the portfolio we should be able to outperform.

James Anders: The story is similar with Fortis. It's a regulated electric and gas utility company, with operations in Canada and the U.S. Over a long history it has consistently delivered earnings growth of 6-8% and paid out 60-70% of earnings as dividends. That's allowed investors in it to earn high-single-digit, low-double-digit returns with a fair degree of certainty. With all the volatility going on globally as risk is repriced and high-beta, high-multiple names take it on the chin, there's something to be said for a company like this that you think can consistently deliver solid, compound shareholder returns.

How generally do you unearth ideas?

RJ: We have developed a quantitative scoring and ranking system that we apply against a 50,000-name investable universe of globally listed, actively traded equities. While it's not possible to capture forward-looking quality in a quantitative screen, we're able to use common metrics of balance sheet strength, profitability, efficiency and sustainability to identify companies that at least in the past have exhibited the classic attributes of quality.

ON BUSINESS QUALITY:

Everyone talks about buying quality, but you have to be sure you’re not anchored to backward-looking quality.

That scoring system focuses us on a concentrated inventory of companies – across our portfolios we own maybe 100-110 names at a time – that we monitor on an ongoing basis. We're basically recycling a small group of names based on the fundamentals. That circle changes slowly.

Look at European banks. A few years ago we had 30% of the international portfolio in banks, which went to 0% for a while, and which now is back up to a much higher exposure again. We will never go in and say, "European banks look great, let's go find names to fill out a target allocation," but as the context in an industry changes we'll look closely and try to distinguish the good from the bad.

The Spanish banking sector, for example, is much healthier than it has been in a while. The economy is in better shape. The housing market is improving. The banking system is better capitalized. But in many instances, as is the case elsewhere in Europe, the banks are valued based on the last war, the financial crisis, not on what's coming next. As we dig deeper, we'll be drawn to something like Bankinter [Madrid: BKT], which we consider best-of-breed, with strong market positions and we think sustainable earnings prospects. On the other hand, we'll pass on something like BBVA [BBVA], which screens as cheap, but has significant exposure to non-Spanish markets like Mexico and Turkey, where the industry context isn't as positive.

Brian Kersmanc: I'll give another example that I think illustrates how we work. We have a devil's-advocate approach, and many times Rajiv does the initial work on names himself. He'll then come to an analyst, say he thinks something may be interesting, but then won't tell us a lot more and asks us to find the flaws in the positive thesis. A couple summers ago he had done some research on Rolls-Royce [London:RR], which makes engines for wide-body airplanes and power and propulsion systems for ships. The airplane-engine business is the crown jewel, with an annuity-like business model where you sell an engine at cost or even a loss and make it up in the aftermarket with long-term contracts for parts, maintenance and repair. The secular trends for airplane demand were also extremely strong, with order books for both narrow-body and wide-body planes going out eight-plus years. The company had had some execution issues and people didn't like the marine business, so the potential was that the stock had been unduly punished.

There were some things I didn't like. One big one was that while plane orders aren't often cancelled, they can be pushed around and delayed, and there seemed to be more risk of that in the wide-body arena, because of where we were in the cycle, who some of the biggest buyers were, and because of a trend in the airline business toward smaller planes flying more point-to-point like Southwest does in the U.S. Narrow-body planes require less capital upfront and are easier to fill.

Another important issue was that in a field where management has quite a bit of leeway in how they book revenues for upfront and aftermarket sales, it appeared Rolls was kind of consistently taking the more aggressive route, which had the effect of pushing profits forward at the expense of profits later. We believe that many times really understanding the accounting can provide a better sense of management's thought process and the culture of the company than listening to them speak. In this case, that was a concern.

As part of my due diligence I looked closely at the big aircraft-engine competitors, MTU Aero [Xetra: MTX] and Safran [Paris: SAF]. Safran was particularly interesting because in addition to having the positive business-model aspects of Rolls, it – in a joint venture with GE Aviation – was the dominant player in the narrow-body end of the market where I thought the order book was much safer. Management in this case had a reputation for conservatism in accounting, and for underpromising and overdelivering on performance metrics. There were issues weighing on the stock – which, by the way, Rajiv pushed back with when I brought him the idea – around the transition to a next-generation engine and over the potential acquisition of a plane-seat manufacturer called Zodiac Aerospace. In both cases, I thought management had a track record and a plan that gave me confidence the market concerns were overdone. Long story short, the original idea to look at Rolls-Royce ended up in our buying Safran.

Looking at Safran's stock chart, that's worked out nicely. Is it still interesting?

BK: We think there's still plenty of upside opportunity. They did buy Zodiac and are executing on it better than people thought. The previous-generation narrow-body engine, the CFM56, has remained popular and there's a big wave of those engines coming in for overhauls that will drive high-margin aftermarket revenues. The new-generation Leap engine has also been very successful. We think over the next five years earnings can compound at a mid-teens rate, which assuming as we do that the multiple stays fairly constant, would provide an attractive shareholder return.

You mention the signaling you can get from fully understanding a company's accounting. Talk more about that as an element in your research process.

RJ: I do believe our accounting emphasis has given us an edge. As Brian mentioned, interpreting the accounting is important in understanding the company culture and how management thinks. You typically don't get aggressive accounting by conservative management.

ON ACCOUNTING:

Accounting reflects the culture. You don't often get aggressive accounting from conservative management.

Many technology companies in the U.S. use, let's say, interesting accounting. With all the pro-forma adjustments and exclusions it can be difficult to figure out the true earnings power of the business. My general view is that if management is so focused on managing the short-term numbers, they're less likely to be as focused as they should be on the longer-term fundamentals of the company.

On the other hand, the fact that Alphabet over the past year or two has deemphasized pro-forma numbers and focused on more-conservative U.S. GAAP results is to me an important signal. They're essentially downplaying the short term, which could indicate how bullish they are on the business long term.

An emphasis on accounting also can help you avoid disasters. I keep finding new ways to lose money, but I haven't lost money from an accounting fraud so far. Valeant Pharmaceuticals was a perfect example. I made money with it very early on, but even in 2013 the accounting was very aggressive and getting progressively more so. I sold and wasn't happy at all as the stock kept marching up, but was very happy I had when everything fell apart.

On the subject of reacting to data points, as you put it, kudos for selling out of General Electric [GE] in the third quarter of 2017. What do you see then of concern?

RJ: We can only predict so much, but things generally emerge over time and we have time to react. With Valeant there was plenty of time to react to accounting-quality deterioration and the signs of hubris in management. Those aren't things you can predict, but when you see them maybe you should do something.

With GE, we knew the businesses they were in and the environment in those businesses and it just seemed as if they were making a bunch of excuses for underperformance that didn't match up with what was actually going on. At the same time, the accounting was getting both more complex and somewhat more aggressive. It was all about weighing the positives and negatives and I came down on the side that I didn't have a clear enough view on how the business could perform over the next five years. If that happens, I'll back off. You can always revisit it again.

How are you reacting to the data points today on Facebook [FB]?

RJ: The business is phenomenal. They have an amazing market position. The stock doesn't look expensive. The key issues an investor has to think about are the cultural aspects of how the company has behaved, how high the regulatory risk is, and how all that's going on will impact the company's underlying earnings power. I'll leave it at that.

How about the same question on China's Tencent Holdings [Hong Kong: 0700]?

RJ: This also is a phenomenal business and the stock has been a home run for us. But it's not the same regulatory environment for them. Certain videogames are not getting approved. There are increasing restrictions on digital advertising. There's tighter regulation in fintech. The environment has shifted to the extent that we aren't comfortable holding the 6-7% position we had, so we've reduced it. Again, we can always revisit as new data emerges.

ON INVESTING IN TOBACCO:

We don't think many of the tobacco stocks reflect that the future looks a lot worse than history suggests.

I'd make a broader point: Quality is forward looking. Today everyone talks about buying quality at sensible prices, but you have to be sure you're not overly anchored to backward-looking quality. Ten years ago maybe you could buy tobacco stocks at cheap multiples and count on the historical sustainability of the business to work its magic. That's gotten harder to do. For investors today there's a higher premium on understanding the current environment and how the sustainability of the business might be shifting going forward.

Are we to take that to mean you don't like tobacco anymore?

RJ: We used to have a lot of exposure to tobacco but now we have none. The market has changed. Emerging-market volumes are declining and contraband products are taking more share. In the U.S. there's the e-cigarette, which has lowered competitive barriers dramatically. When a company like Juul can come out of nowhere and generate the market share it has, that tells you the business has fundamentally changed. That's left legacy players having to spend more on capital spending and R&D to catch up. Why is that business as usual? We don't think many of the stocks adequately reflect that the future looks a lot worse than history suggests.

How generally do you go about valuation?

JA: We're business analysts first and foremost, so valuation is usually the last thing we look at. We'll do an earnings model out five years and apply what we consider a multiple representative of the opportunity from there. We then discount the resulting price back to the present at a 6% rate – which builds in kind of a worst-case return if we're directionally right – and then want to buy at a discount to that intrinsic value so we can, with dividends, compound at least at a 10% or so rate. We generally don't expect to be helped or hurt by any multiple change.

Within the past year Intuitive Surgical [ISRG], which you own, has been listed as the most-expensive stock in the S&P 500. Is the upside you see in the business just so high that it doesn't matter?

BK: The price you pay always matters, but this is a company with a lot of headroom for growth. It is the dominant competitor in robotic surgery, with an installed base of 4,500 machines, versus the next closest competitor's 10. It's a razor/razor blade business model, with 70% of revenues in high-margin recurring instrument sales, but the "razor" itself costs between $500,000 and $2.5 million and also generates excellent margins. The market overall is still in its infancy on a global basis.

If we look out five years, if anything there's a good chance the growth headroom is increasing. If that means the multiple doesn't shrink, we'll benefit from annual earnings growth that without stretching could be 15%, 20%, or more. We're aware, especially in today's market, that we shouldn't overpay for growth. In this case, we don't believe we are. [Note: At a recent $471, ISRG shares trade at 37x consensus 2019 EPS estimates.]

Turning to a few of your portfolio-management guidelines, why do you limit yourself to a maximum 20% overweight by country relative to the index?

RV: We generally think it's a good idea to have country diversity in a global portfolio, due to geopolitical and currency risks. We also don't think our investors want to worry about our taking on outsized country exposures. It's consistent with what I said about compounding. We're not trying to hit home runs, which in this case could mean taking on excessive country risk.

We have other guidelines that are similar. We generally want to own at least five industry sectors in an individual portfolio. We limit our maximum position sizes to 7%. There's nothing magical about any of that. My whole investing premise is sort of that you only know so much in this business. These types of things acknowledge that unknowability.

I don't want to give the impression we're managing to the index, plus or minus. In a global portfolio we have tremendous flexibility by country and by company. Our active share is typically 90%-plus.

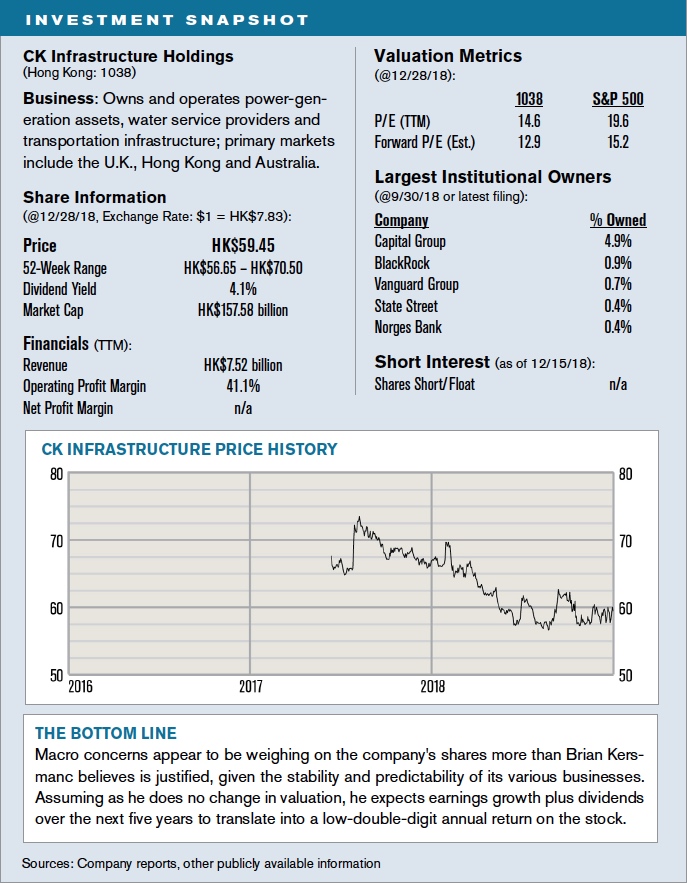

Does your holding in CK Infrastructure [Hong Kong: 1038] reflect its status as a durable, if unsexy, compounder?

BK: The company is the infrastructure business of Li Ka-Shing's CK Hutchison, which still owns a roughly 70% stake. It started out with a large power-utility business in Hong Kong and has expanded beyond that by adding power-generation, energy distribution, rail infrastructure and water and wastewater services in multiple countries. The U.K. now accounts for more than 40% of total revenues and is the largest market for them, with Hong Kong the second largest at about 25% of sales. They're solid operators who have built a portfolio of toll-taker, nicely cash-flow-generative businesses.

Although the businesses themselves are asset-intensive, CK's strategy is typically to buy large chunks of independent companies, sometimes consolidating them on the balance sheet and sometimes not. As the different units grow and develop, CK may sell down part of a stake and reinvest the proceeds elsewhere to further diversify and augment growth. They're like a portfolio manager of infrastructure assets. The leverage can be fairly high – net debt to EBITDA today is at 6.7x – but that has been much lower at times depending on asset selling and buying. For example, they're currently talking about selling down a portion of the U.K. assets to raise money for further investment.

Li Ka-shing, one of the world's richest people, turned over the reins to CK Hutchison in May to his son. Any concerns over that for CK Infrastructure?

BK: The CK Infrastructure management team is intact and very capable. At the parent-company level, it's a large company with a number of talented, long-tenured executives, and the CEO transition has been in the works for a very long time. We don't see execution risk around the change.

Given the U.K. exposure, is Brexit a risk?

BK: There might be some currency risk and some utilization risk with rail assets, but by and large the businesses they're in – in the U.K. and elsewhere – are incredibly stable, with very long-dated contracts and mostly guaranteed regulatory returns.

If I were to highlight a risk it would be around increasing tension over trade with China. As a Hong Kong-based company, it's conceivable CK will find it somewhat harder to invest in European and North American assets because of the Chinese connection. The company has always operated independently of the government, but some stigma attached to China could be a worry down the road.

How are you looking at upside from today's share price of HK$59.50?

BK: With just the assets they currently have, we believe the company with a fairly high degree of certainty can compound earnings per share at 6-7%. The dividend yield is better than 4%. If we assume a constant multiple of around 13x forward earnings – we see no reason for it to be lower in five years – that would translate into a low-double-digit annual return on the stock.

RJ: I spoke earlier about recycling ideas with some regularity. This was a top-ten position of mine two and a half years ago but I sold out primarily due to valuation. The stock has now fallen quite a bit since then, in large part because of concerns about rising interest rates, and the multiple is down from 16-17x forward earnings to less than 13x today. Now it's become interesting again.

Explain why you're optimistic about the future prospects for beer-maker Heineken [Amsterdam: HEIA].

JA: Heineken is the world's second-largest brewer and its flagship brand is the top premium lager globally. That premium positioning is a key differentiator. If you think about the major issues in the beer world, where Anheuser-Busch InBev is cutting its dividend and the market is very worried about its debt load, the mass market is where the primary competitive and pricing difficulty is. Heineken with its positioning has avoided much of that and is still showing volume and revenue growth that mass-market beer makers haven't.

While the company is based in Europe, we see the biggest opportunities for it in key emerging markets such as Mexico, Vietnam, Brazil and China. Both Mexico and Vietnam have highly attractive demographics for beer consumption, and the company continues to successfully expand its distribution and market position in each country. In Brazil, we see significant upside following the 2017 purchase of Kirin Holdings' operation there. Kirin had built out valuable distribution capability, but the business earned no money. Heineken expects the country within five years to be generating operating margins close to its group average of 17%.

In China the company announced in August a strategic partnership with China Resources Beer, the market leader with a roughly 25% share. As part of the deal Heineken acquired 40% of CR Beer Limited, which sells Snow, the top mass-market brand in the country. There is some skepticism about the deal because SABMiller had tried something similar in the past that didn't work out, but Heineken's product portfolio is far more complementary and the upside for it in tapping CR's excess production and distribution capacity in the largest beer market in the world is pretty dramatic.

I'd mention that not every emerging market is firing on all cylinders. In Nigeria, for example, beer taxation has become more onerous and, more importantly, A-B InBev is aggressively going after market share on price. While that is hurting Heineken's business there, we don't believe trying to win only on price is going to be a lasting solution for Anheuser-Busch. This is an area to monitor, but we don't see it as a long-term negative.

Are some of the less-than-positive trends in beer consumption in developed markets a concern?

JA: In the markets we see as the growth drivers for the company, you're not seeing the impact of beer substitution you may be seeing in more developed countries. At the same time, the shift to craft beer has been more of a U.S. phenomenon, which Heineken because of its more premium positioning has not been as impacted by. In fact, the trend toward premiumization, in both developed and emerging markets, should continue to be a tailwind for them, not a headwind.

In general, the company's track record of innovation in response to changing consumer preferences has been quite good. They've successfully extended the Heineken brand with things like extra-cold and non-alcoholic versions, for example, and they have a leading alcoholic-cider business in Europe. We're also positive on the expanding tavern business in the U.K., which has proven successful in its own right and also keeps them very close to what the beer-drinking consumer is doing.

The shares, trading recently at €76.50, aren't much higher than they were four years ago. How are you looking at valuation today?

JA: The valuation story here is similar to what you've heard already. We think the upside in emerging markets can drive earnings growth in the range of 10% per year over the next five years. There's a 2% dividend yield. We'd expect the earnings multiple, now about 17.5x forward estimates, to be at least static. If that all works out, we'd get to the type of double-digit compounding return we're trying to deliver to our investors.

From beer to banks, describe your interest in Belgian bank holding company KBC Group [Brussels: KBC].

JA: The company was formed twenty years ago by the merger of two banks and an insurance company, and it now offers traditional commercial-banking, retail-banking and insurance services in a number of Western and Eastern European countries. Belgium accounts for roughly 55% of the net results, but they also have successful franchises in the Czech Republic, Hungary, Ireland, Bulgaria and Slovakia.

KBC had an excessive derivatives exposure going into the financial crisis and ended up having to be bailed out by the Belgian government. The positive result of that – as with a number of European banks – has been that since that time they've been focused solely on their traditional banking and insurance businesses and on rebuilding the capital base. KBC is now one of the best-capitalized banks in Europe, with a core Tier 1 capital ratio of 16%, well above requirements and peer levels.

There are a number of hotbed countries now Europe. Italy's fiscal situation is difficult. France is trying to institute the types of labor and economic reforms Germany did 15 to 20 years ago, which is causing unrest. In contrast, KBC is in markets that have been relatively immune to a lot of the problems. While a number of other big European banks are still struggling with poor loan growth and limited net-interest-margin expansion, KBC is by and large bucking those trends.

You wouldn't know that from the share price, which at a recent €56.40 is down nearly 30% from earlier this year.

JA: That's at the root of what makes this interesting. It's being painted with the same broad brush as its banking peers, so we'd argue is receiving less credit than it should for its solid balance sheet, good operating execution, capital generation and, ultimately, capacity for capital return.

We think the company can continue to generate high-teens, low-20s types of ROEs, which translates at their high capital ratios to earnings growth of maybe 6-7%. But they're also generating roughly 2% per year in excess capital, which gives them significant capacity for capital return through either dividends or share buybacks. With the earnings growth and capital return, this is another of those ideas we think can compound returns for shareholders in the low-double-digit range.

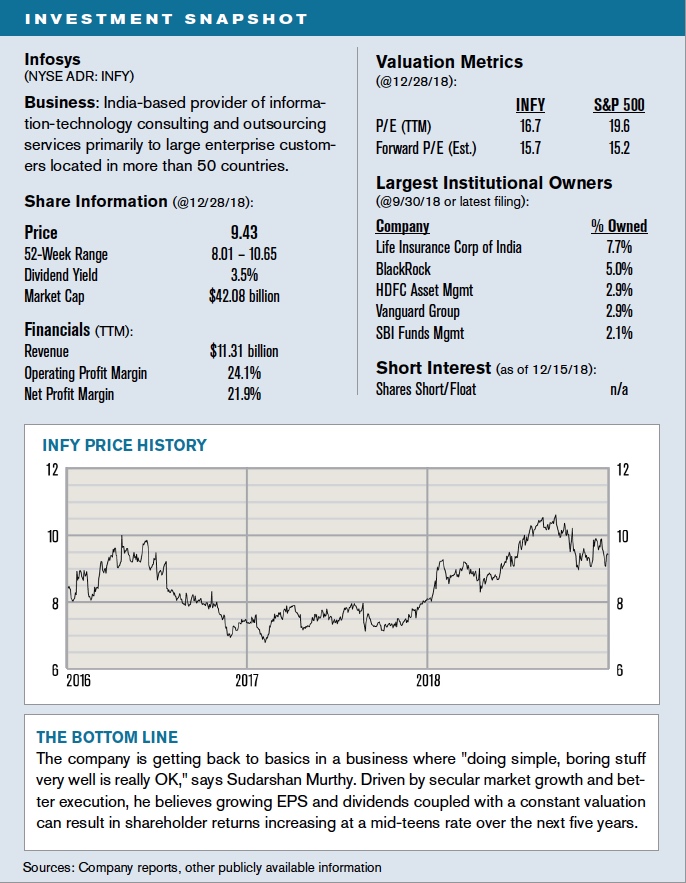

Is Infosys [INFY] more of a turnaround story for you than usual?

Sudarshan Murthy: The company started in the early 1980s with a relatively simple premise. As information technology proliferated and demand for IT processing and services grew, the company was built to take advantage of labor-cost savings from using Indian engineers to help handle companies' growing IT-related workloads at lower cost. Firms like Infosys, Accenture and Cognizant grew rapidly as they developed much broader capabilities and geographic reach. Infosys today has more than 200,000 employees, operates in more than 50 countries and serves more than 20 different industry sectors.

In 2014 the company brought in a new CEO, Vishal Sikka, who tried to change the DNA somewhat. He had spent many years at Germany's SAP and wanted to shift Infosys away from more traditional outsourcing services toward a greater focus on the development of proprietary software. Some of the basic ideas made sense – such as accelerating the build out of capabilities around things like cloud computing, data mining and the Internet of Things – but the execution overall caused a great deal of consternation both among employees and the customer base. Sikka resigned 18 months ago.

Fast forward to today and the company, now run by a CEO with an IT-services background, is basically making a back-to-basics push. We see that very much as a positive. Infosys works with large, sophisticated clients who have a good sense of what they want their technology to be and call on companies like Infosys to help them implement it efficiently and effectively. They don't have to wow everybody with the latest new product – doing relatively simple, boring stuff very well is really OK.

Are you still bullish on the IT-outsourcing business in general?

SM: The nice thing about this business is that any time there is a disruption in technology –which happens with regular frequency – companies have to upgrade themselves and service providers like Infosys are clear beneficiaries of that. Once you're established with a client, the business tends to be extremely sticky. Switching vendors can be a risky proposition that CIOs who care about keeping the trains running on time don't at all take on easily.

Infosys' organic growth seems to be coming back. They added more people in the first half of this year than they had collectively in the previous two years. They're winning a sizable number of contracts – the contract value of large deals won last quarter came in at the highest level ever recorded. Overall, from industry growth and better execution in the market, we're counting on the company growing its top line at a 10-12% annual rate.

How are you looking at valuation with the U.S.-listed ADRs trading at $9.40?

SM: The multiple today is 15.7x March 2020 estimated EPS of around 60 cents. Compared to the company's historical range that's somewhat average. If the multiple stays constant, even assuming no operating leverage and no share buybacks, the combination of earnings growth and the 3.5% dividend yield would get us to a mid-teens annual return on the stock.

The big thing to watch is how successfully the company addresses employee-attrition issues that worsened under the prior CEO. Management is working to better align incentives and get attrition under control. It's something to monitor – difficulty in holding on to people will make it harder to grow at the rate we expect.

Describe your investment case for New York Stock Exchange-parent Intercontinental Exchange [ICE].

JA: Exchanges are interesting to us as steady-Eddie compounders. You might think the business is very dependent on trading volumes, but roughly half of ICE's revenues and operating profits now come from its data and listings business, which sells – often for recurring fees – a wide variety of critically important equity and fixed-income market and pricing data. Overall, there's a toll-taking aspect of the business we find quite attractive.

Including the NYSE, the company operates 12 exchanges for trading equities, fixed-income securities, futures, options, oil contracts and a number of other financial instruments. Customers pay ICE to execute and clear trades, but also for real-time pricing, historical pricing and an increasing amount of data analytics that help them make decisions, manage risks or even administer their own products like ETFs. Both sides of ICE's business are high margin: operating profits for trading and clearing run in the mid-60% range, and for data and listings they're above 50%.

Are you counting on increasing market volatility to drive trading demand?

JA: That would be a positive, but the growth drivers we're counting on are more around higher trading volumes due to passive and algorithmic trading, greater data and analytics demand due to increased compliance and regulatory requirements, increasing institutional demand for customized data to better manage financial risks, the proliferation of ETFs needing pricing and listings data, and increasing concerns over financial data security.

As these trends play out, we don't think it's unreasonable to expect the company to generate earnings and cash-flow growth at a mid-teens rate over the next five years. For perspective, ICE's EPS compounded at 18% per year from 2006 through 2017.

The shares, now $74.50, trade at 19x consensus 2019 earnings estimates. Are you expecting as a shareholder to at least capture the prospective earnings growth?

JA: Yes. We're not counting on a change in valuation, but exchange companies often trade in the 20-22x multiple range, due to their consistent growth, strong profitability and generally solid earnings outlook. There's no reason to expect that to change.

Rajiv, in the past you've been labeled, even with the same fund, as both a growth and a value manager. Is the argument for one style or another sometimes a distinction without a difference?

RJ: Every investment decision has to be predicated somehow on buying things at a discount. But you have to adapt and evolve because exactly the same mousetrap isn't going to work forever. Just buying low-price-to-book or low-P/E stocks maybe doesn't work the way it did 12 to 13 years ago. Maybe there's more importance now on the sustainability of the business. Maybe growth adds to value and means you don't need a catalyst other than that.

I've always been a stock junkie, reading anything and everything I could get my hands on from successful investors. But I've never really had a mentor. Investing is nothing but a journey of learning from mistakes and getting better at it. If you're not willing or able to do that – however you define yourself as an investor – you won't survive over the long term.