Alexander Roepers Rossana Ivanova Andrew Black Toni Bujas Atlantic G4S Atos Oshkosh OSK Avnet AVT CommScope DXC Owens Illinois Worldline Diebold Nixdorf

How you define your opportunity set says quite a bit about your underlying strategy. Describe where you will and won't look for ideas.

Alexander Roepers: Our universe consists of companies with $1 billion to $20 billion in market cap in the U.S., Europe, Japan and some Asia, ex-Japan. Because one of our key tenets is to concentrate on high-conviction ideas – our long portfolios have between six and maybe 20 names – we also try to avoid a number of particular idiosyncratic risks. We avoid high tech due to the risks of technological obsolescence. We avoid most financials due to the lack of transparency, and we avoid industries like utilities and cable television, which are subject to significant government intervention. We won't take on the potential for product-liability risk that comes with investing in tobacco or pharmaceutical stocks.

The market cap range reflects the fact that we would like to always be a significant minority shareholder, holding between 1% and 7% of the shares outstanding. This facilitates engaging in constructive conversations with top management about their companies and their plans to improve shareholder value over time. Our activism is liquid activism, meaning we engage in a constructive manner and won't hesitate to be increasingly vocal when the situation warrants, but we also avoid board seats and proxy battles that can make us illiquid by virtue of our activism. We want to be able, without constraint, to size positions as we see fit when we believe the risk/reward becomes more or less attractive.

ON CONCENTRATION:

Because we concentrate on high-conviction ideas we also try to avoid a number of particular idiosyncratic risks.

After we narrow the broad universe by market cap and key risk areas, we focus further by only including companies that have solid balance sheets, which we define as having annual interest expense of less than 25% of earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization (EBITDA). We want companies that are always profitable, with positive operating profit through economic cycles, and that have predictable cash flows, from the recurring nature of the business and/or diversification across customers, products or geography. Finally, we're looking for classic sustainable competitive advantages, from things like strong brands, hard-to-replace assets or high entry barriers. All told, our target universe globally is about 1,400 names.

From there is it as "simple" as zeroing in on the best bargains?

AR: We're trying to pinpoint inflection points for both material improvement in operating performance and in share-price appreciation. So, yes, that means we have a strict valuation discipline and we're often getting involved when stocks are already down substantially. But we also need to see multiple catalysts for improvement, from a change in market dynamics, the evolution of a cycle, or any number of corporate actions to improve operating results and otherwise unlock value.

An example of something we were buying last quarter is CommScope [COMM], which is an integrated manufacturer of equipment used for wired and wireless communications. In the middle of last year they issued an earnings warning that we felt wasn't that severe – primarily from giving up some pricing to large customers to add volume and lock in business under long-term contracts – but the market took the stock down 30%. Then they issued another earnings warning and in the middle of all that announced the $7.4 billion acquisition of a large competitor, Arris Corp., and the stock kept going down.

We know the company and industry well and expect the combined business to benefit from its leading position in a secular-growth market. The Arris deal should be highly accretive, expanding CommScope's product portfolio, reducing its customer concentration and producing cost synergies on the order of $150 million per year. There's operating leverage and financial leverage as they use cash flow to pay down debt, and we think earnings per share can come relatively quickly to more than $3 per share. At today's share price [of around $21], that's only a 7x forward P/E. If our expectations about earnings and the deal benefits are right, this shouldn't trade at a 7x P/E.

Does your constructive activism approach influence your research due-diligence.

AR: Most of our initial fundamental research, I imagine, is consistent with what other investors do. We generally already know the businesses very well, but the first order of business is always to review everything we can on the company, both from the company and from any number of sources outside the company, including vendors, customers and competitors. We want to meet with management early in the process, to try to build some rapport, to see how willing they are to listen to engaged shareholders, and to see with our own eyes their operations. That all makes up our first level of diligence.

Andrew Black: We're also fairly early on trying to identify the key pressure points on the specific company and stock, to better understand what's going on and judge whether we can get comfortable with the idea. We'll talk later about the investment case for it today, but when we first got interested in technology-product distributor Avnet [AVT] in 2017, two main things had happened. The company had made some significant changes in its business portfolio, selling off what it considered a lower-margin, lower-growth business called Technology Solutions, and buying what it considered a higher-margin, higher-growth business called Premier Farnell. It was also going through a terrible implementation of a new Enterprise Resource Planning [ERP] system, which had resulted in about $1 billion in lost revenue. The stock had been punished badly and we became interested.

So our research focused on proving whether or not those two events were going to end up being positive. We spent a lot of time on field research, interviewing suppliers, customers and competitors to see if the bleeding had stopped around the ERP-system transition. We also dug deeply into how the business model was evolving and whether the portfolio transition was going to enhance or destroy value. In managing our time, it's important to identify the primary hurdles and see if we can get over them before moving on. Often we can't, but in this case we could.

AR: I'd emphasize here that our interest in any investment starts with a good value story. That means that without any brilliance from management or from our involvement, we expect to be well rewarded because we're buying a company with strong fundamentals, a solid balance sheet and a good business mix, that's trading at the low end of its valuation range –5-6x EV/EBITDA or 7-8x EV/EBIT – and we're expecting with reasonable execution and sort of average performance that within one or two years the stock can trade at the higher end of its valuation range, say 8-9x EV/EBITDA or 10-12x EV/EBIT. If that happens, we'll have a very attractive return – again, it all starts with a well-timed value idea.

I should also mention that from a value perspective, we think our portfolio today is extraordinarily attractive. The entire portfolio trades at less than 7x EV/EBIT.

Do all of your ideas have to have an activist component?

AR: To the extent that we lay out in each case a corporate-action recipe focused on what management should be doing, yes. It's obviously customized to the situation, but the action plan typically involves corporate development, operational restructuring, capital allocation, improved investor relations or improved corporate governance. It includes anything we believe management should be doing to increase shareholder value over time.

ON TODAY'S OPPORTUNITY:

We think our portfolio today is extraordinarily attractive. The entire portfolio trades at less than 7x EV/EBIT.

There are times when they're doing largely what we'd prescribe and we don't feel the need to push them in a different direction. One of our more recent core positions, for example, is DXC Technology [DXC], which was formed in April 2017 when Computer Sciences Corp. merged with the enterprise-services arm of Hewlett Packard Enterprise. The CEO, Mike Lawrie, has an excellent track record with a proven shareholder orientation and we believe at the moment that he's doing the right things from an operational perspective and that he has significant flexibility to pivot the company now to growth, which is something the market appears quite worried about.

In a case like this – again, at the moment – we don't believe we need to be vocal with management. At today's share price [$64.20], the stock trades at around a 13% free-cash-flow yield based on our 2020 numbers. With good execution and basic blocking and tackling, we see plenty of upside over the next 12 to 24 months.

Why have you decided it's time to be vocal with management at glass-container manufacturer Owens-Illinois [OI]?

AR: We have a good rapport with management and they execute well. They bought back shares, initiated a dividend and have laid out a credible road map for higher earnings. But with the valuation-compression situation we see hitting global industrials – while investors flock to technology and perceived high growth – the stock has gotten so beaten down that we think the company is vulnerable to private equity stepping in and trying to buy it on the cheap. That would likely steal the upside that patient, and frustrated, public shareholders have been waiting for.

What one does then is to roll up their sleeves to look at creative ways to enhance shareholder value. Here we've concluded that the company should pursue the sale of its entire European operation, which is roughly 40% of the company. Acquisitions in the space, including those made by Owens-Illinois, all go for 7.5x to 8.0x EV/EBITDA, while the company's stock has been trading at 5.5x to 6.0x. We have pointed out that instead of buying, maybe they should be selling.

As a bit of an aside, are there any secular issues around glass containers you might be underestimating?

AR: The narrative against glass containers is that there's no growth. But Owens-Illinois's volume in North America grew 20% from 2012 to 2018, partly from taking share and partly from a mix shift in the business away from mass-market beers and toward imported and/or premium beers and spirits, which tend to come in glass bottles.

There's also an environmental angle. Plastic is getting hit hard on that front, while glass stands up well against packaging competition when it comes to sustainability and ability to recycle. We'd argue, in fact, that there are secular tailwinds.

How have management, and the market, responded to your latest proposal?

AR: The company has pushed back on the idea, and so far nothing new has happened. The stock reacted reasonably well, maybe somewhat from our efforts, but also because the company is performing. There's a convincing road map in place with 10% compound annual earnings growth from the $3 in EPS they've guided to for 2019. A company like that shouldn't trade where it trades today. [Note: Owens-Illinois shares closed recently at around $19.75.]

You trade considerably around positions. What's the rationale for that?

AR: Our longest-running fund usually holds six stocks. Given our typical holding period of 18 to 24 months, the name turnover is about 50% per year. The total turnover, though, is closer to 100%, which comes from actively sizing positions, sometimes almost every day.

The basic premise is that as a stock moves up or down, we'll trim it back or add to it to keep the position size at the percentage of the portfolio we consider appropriate for the risk/reward at that moment. Say something goes from $30 to $38. Even if we have a $50 target, at $38 the risk/reward is less attractive than it was at $30, right? If it's a core 15% holding, we might be trimming every day as it moves from $30 to $38, and by the time it gets to $38 the position size is down to 12%. If there's some bad news and the stock falls back to $32, maybe making up 9% of the portfolio, if appropriate we'll be buying to build it back up to a 15% position. It's like an accordion.

We do it in order to generate alpha. In our U.S. strategy we've determined that about 20% of our gross returns have come from this type of dynamic trading around core positions. It's an important part of what we do.

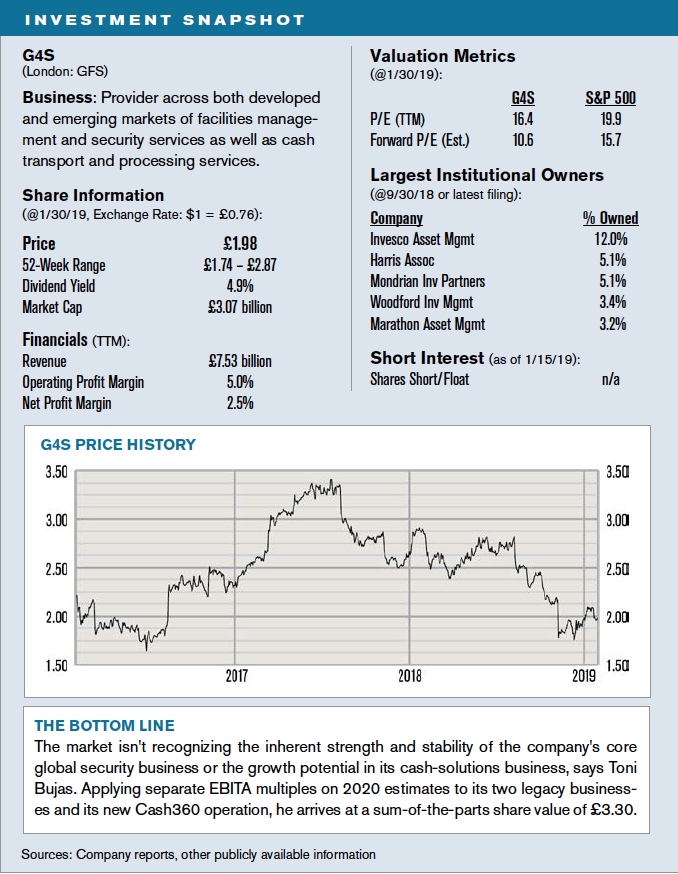

Europe has been a fertile source of ideas for you of late. Describe your investment case for U.K.-based security firm G4S [London: GFS].

AR: G4S is one of the two largest global providers, along with Securitas, of manned security for buildings, airports, retailers, financial institutions and government agencies. We're attracted to both the broad geographic and end-market diversity of the business, as well as the underlying secular growth in demand for security services. It's also a cash-generative business, with multiple touchpoints that increase the stickiness of relationships and result in 90% client-retention rates. As just one example, they may provide office security for a large corporate client in addition to regular risk-assessment analysis for executive travel.

The company also has a cash-solutions business that transports cash and operates networks of ATM machines. In our view, part of the mispricing in the shares is due to investor skepticism of this business because of growth in electronic payments. In reality, cash in circulation and ATM usage have been very stable in developed markets and are actually growing in emerging markets.

Toni Bujas: Another misperception in the market has to do with their Cash360 business, which we consider a hidden gem. The Cash360 machines were co-developed with Walmart and provide a creative solution to a common problem for many retailers. Store employees take cash from the register to the back office, count it, and put it in a safe, often multiple times per day. The cash is then usually transported to a local Brink's or Loomis office, and ultimately to the retailer's local bank. This is a 19th century solution that is laborious and creates up to a three-day lag between when the cash goes in the register and when it is credited to the retailer's account. By comparison, a Cash360 machine automatically counts the till, acts as a safe, and credits the retailer's bank account the same day.

Having implemented these machines in all U.S. Walmart and Sam's Club stores, Walmart has reduced back-of-store cash-management headcount by 7,000, working-capital efficiency has improved, and cash theft has declined. Target has signed on as the second-largest Cash360 client, and is currently onboarding about one-quarter of its stores, with plans to roll out across all stores in the next 12 to 24 months. The number of pilot programs for Cash360 has doubled to 25 retailers in the past year, and we expect many of those to convert to revenue throughout this year and next. The names of the retailers haven't been disclosed, but we believe one is Home Depot.

The shares, now at just under £2, are down 30% in the past year. How are you looking at upside from here?

TB: The general stock-market weakness in Europe has obviously been an issue, but we also think there's a further misperception about the Cash360 business. Revenue growth for it looked bad in 2018 because of how the massive Walmart installation was accounted for in the prior year, but we don't believe that reflects the excellent growth potential of the business.

Our sum-of-the-parts valuation assigns multiples of earnings before interest, taxes and amortization [EBITA] on our 2020 estimates. We use 12x EBITA for the core security business and 11x for the legacy cash-solutions operation, both well within historical ranges for comparable companies. For Cash360 we use 14x EBITA, which is likely conservative given its 30% growth rate. That all sums to £3.30 per share, implying nearly 70% upside from the current price.

We consider the downside limited, given that the shares trade at only 10.5x estimated 2019 earnings, the dividend yield is nearly 5%, and that management announced in December it was exploring options to potentially break up the company to unlock shareholder value. G4S was actually offered more than £1.5 billion for its cash-solutions business five years ago, pre-Cash360. Considering that cash solutions accounts for about 25% of group operating income and the current market cap is just £3.1 billion, it's clear to us that there's plenty of value to unlock. As an asset-light, stable business, we'd argue the whole of G4S would make an ideal leveraged-buyout candidate.

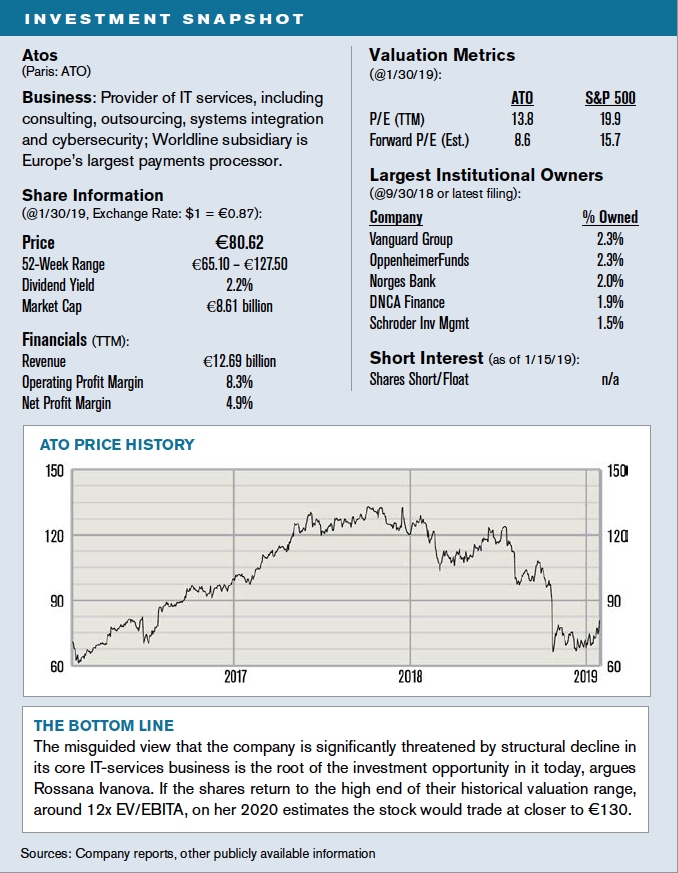

The shares of French IT-services company Atos [Paris: ATO] also appear quite unloved. What do you think the market is missing?

AR: The company provides a range of information-technology services, including infrastructure management, software integration and cloud migration. We first became involved with it in 2010, attracted to its growth strategy and its high-margin payment-processing business called Worldline. At our first meeting with management we suggested they borrow money on their debt-free balance sheet, repurchase stock that was cheap at the time, and IPO a portion of Worldline to unlock value. They could then use the IPO proceeds to pay down the debt for the buyback.

Instead, the company acquired Siemens' internal IT business in exchange for 15% of the shares in Atos. That made Siemens an important shareholder and an important client, signing a €5.5 billion, seven-year contract for services that has since been renewed. That worked well and we as shareholders benefitted from the company's resulting growth on the top and bottom lines. We also dusted off our letter recommending the partial spinoff of Worldline, which the company did in 2014. By 2017 the shares approached our estimate of fair value and we sold.

We started again accumulating shares early in 2018 after a cold reception by investors to the company's acquisition of Syntel, a U.S. information technology company. The $3.4 billion price to acquire $1 billion of revenue wasn't cheap, but Syntel's margins are triple those of Atos, it adds a highly complementary customer base in North America, and it strengthens the company's exposure to growth markets such as the cloud, data analytics and the Internet of Things. In October, the shares took another hit, which we considered a massive overreaction, when management somewhat reduced its revenue-growth guidance for 2018 and 2019.

How is the company navigating the growth in cloud computing, which could arguably dampen the demand for traditional IT services?

Rossana Ivanova: The on-premise portion of their business is being cannibalized by the move to cloud computing, but the exposure is manageable as it only represents about 10% of total company revenues. This business is about evolving with technological changes, which the company has done very well over three decades of operation. New technologies give rise to new opportunities, such as providing cloud-migration services in partnership with major cloud providers like Amazon Web Services and Microsoft's Azure, or selling add-on services around enhanced data analytics. According to management, Atos has not lost a client as a result of cloud computing because they still need a service provider for customization and to manage applications and run upgrades.

The view that the company is threatened by structural decline is the root of the investment opportunity. Atos' market valuation today is lower than it was in 2009 when it was a completely different animal with leverage and no free cash flow. Its 51% stake in Worldline [Paris: WLN] is currently worth roughly €4.4 billion, representing over half of Atos's €8.6 billion market cap. Excluding the market value of Worldline, the rest of Atos is trading at less than 6x estimated 2019 earnings and at a 13% free-cash-flow yield.

What potential do you see in the stock from its recent price of around €80.50?

AR: We believe management has a well-thought-out and credible three-year plan for integrating recent acquisitions, accelerating growth in the core business, improving margins and repurchasing shares. We expect operating income by 2020 to increase 40% to nearly €1.5 billion, primarily from synergies related to the Syntel acquisition. On an EV/EBITA basis, the shares have traded in the past five years between 8x and 12x. On our 2020 numbers, at the high end of that range, the stock would trade at closer to €130.

Returning to this side of the Atlantic, the shares of Oshkosh Corp. [OSK] seem to periodically fall into and out of favor with investors. What are the latest concerns?

AR: Oshkosh manufactures a variety of specialized vehicles and equipment, including military trucks, fire and emergency vehicles, waste haulers, snowplows, cement mixers and aerial work platforms. They have nice end-market diversity, and as the North American leader in nearly every category of vehicle they manufacture, the business has proven quite stable.

That said, certain idiosyncrasies have presented opportunities over time to invest in Oshkosh at discounts to intrinsic value. One came from investors overreacting to a big drop in its defense business in the wind-down of the Iraq war. Another was after the company levered up on the eve of the financial crisis in 2007 to make a smart, but terribly timed acquisition of a leading manufacturer of aerial platforms. As end markets dried up during the recession, the shares sold off sharply and we invested as the company worked through that and repaired its balance sheet.

Last year we established a new position yet again as the shares declined by one-third because of concerns about the impact of rising interest rates on construction spending. That's a very un-nuanced view, in our opinion.

Andrew Black: To elaborate on that, private and public non-residential construction spending has been growing in the 4% to 7% range in recent years. Many of the leading indicators, such as the Architecture Billings Index and the Dodge Momentum Index of non-residential projects, suggest low- to mid-single-digit growth in 2019, much better than we believe is being reflected in commercial construction stocks. We also believe the market is ignoring an emerging wave of replacement demand in the aerial-platform business, which should support production rates even in the event of slower demand for new equipment. In addition, any incremental progress on infrastructure spending or the release of pent-up demand for housing would provide additional growth for Oshkosh.

Is the defense business threatened by President Trump's decisions to pull troops out of both Syria and Afghanistan?

AB: That's another popular misconception. Defense is Oshkosh's second-largest operating segment and is actually poised for significant growth. In 2015, the company beat out BAE Systems, Lockheed Martin, and AM General to win a $6.7 billion sole-source contract to supply the U.S. Army with 17,000 Joint Light Tactical Vehicles (JLTV). That program will reach full production in 2019, and over time the ultimate contract value is expected to increase substantially as the Army looks to replace its aging Humvee fleet of over 240,000 vehicles. With an average age approaching 12 years, Humvees are going to need to be replaced regardless of whether the government is pulling out troops in certain areas of the world.

How do you see all this translating into earnings and share-price growth?

AR: We think EBITA quite reasonably can grow by 10% per year over the next two years. We also assume modest debt reduction on an already under-levered balance sheet, and execution of management's stated goal to allocate most of the free cash flow the company generates to the repurchase of 6-7% of the shares outstanding in the next year or so. At even 10x EV/EBITA – well within the historical multiple range of 6-12x since 2013 – the shares on our 2020 estimates would be worth $107. That's close to 50% upside to the current price [of around $72.75].

The shares of Avnet have been dead money for the past five years. Why is that, and what makes it change?

AB: The last few years have been a noisy period for the company as it suffered through the failed ERP implementation and the portfolio transformation I mentioned under the direction of new CEO Bill Amelio, who was previously the CEO of Lenovo. Part of the stabilization process involved over-investing in inventory to improve service levels, which we believed was the right thing to do but it didn't help the operating performance.

One key issue today for the stock is that investors seem to be lumping Avnet with semiconductor manufacturers like Micron Technology and Applied Materials, whose stocks have fallen sharply in recent months due to exposure to saturated smartphone and personal-computer markets. When Apple sneezes and the semiconductor supply chain catches a cold, very often Avnet's stock price is collateral damage. That's despite its much broader end-market exposure and role in providing a critical supply-chain function for more than two million customers across 140 countries.

Looking forward, we think the company is primed to benefit from secular global growth driven by the Internet of Things, factory automation and the proliferation of mobile technologies. With the Internet of Things, for example, semiconductors will be increasingly used across a very broad range of products, whether it's dishwashers, coffee machines, automobiles or traffic lights. Gartner has forecasted that the number of connected devices will nearly quintuple, to 50 billion, by 2025. Regardless of exactly which products win or lose, Avnet benefits from that.

With the shares trading at around $41, how are you looking at valuation?

AB: The core technology-distribution business tends to follow the low- to mid-single-digit growth profile of global GDP, while the Premier Farnell business, which focuses more on earlier-stage technologies, should grow somewhat faster than that. At the same time, we're assuming that the improved business mix and the execution of a detailed cost-cutting plan can expand operating margins from 3.5% to at least 4.5%, and possibly higher. On estimated 4% or so top-line annual growth, if we're right on margins the operating earnings can increase about 50% over the next three years.

The company is also highly focused on improving working capital management and has earmarked $1 billion of cash to repurchase nearly 20% of the shares, generating an estimated $1 per share of incremental earnings. In total, we expect all these initiatives to result in a near doubling of per-share earnings, to $6.50, by the end of the June 2021 fiscal year. At 10x earnings – the shares have historically traded in a range of 8-12x – the stock would trade at $65. Given that the business is of higher quality today, we think assuming just the midpoint of the historical P/E is quite conservative.

You've described Diebold Nixdorf [DBD], the global manufacturer of automated teller machines, as "the worst investment Atlantic has had in its 30 years." What went wrong?

AR: This is an example where we thought an acquisition – Diebold buying Wincor Nixdorf in a deal that closed in mid-2016 – was going to provide substantial opportunity as two similar-sized companies in the same business combined. The prevailing bear thesis on the ATM business is that it is in inexorable decline, and while that may well turn out to be correct over time, as I referred to earlier when discussing G4S, total cash in circulation, total ATM transactions, and the size of the global ATM fleet have all been stable. The issue with Diebold Nixdorf has just been miserable execution. Integration milestones have been missed left and right. Costs have been far in excess of what was expected. That all led to a liquidity crisis last August and the company had to scramble for new financing at high cost.

ON 2018:

We owned companies at 10x P/Es that normally trade at 10-15x, which then ended the year trading at only 7x.

We saw a number of red flags, most having to do with earnings and cash-flow shortfalls exacerbating an already somewhat dicey leverage situation. Another issue was a minority interest in Wincor Nixdorf that suddenly became a short-term liability when the company's financial situation worsened. The biggest lesson? Debt leverage here right after the acquisition was right up against our limit. But the position size we held didn't reflect that the margin of safety was already smaller. We're learning from this and being more cognizant of position size when debt leverage is near the edge.

You mentioned your portfolio is trading at very attractive valuation levels. Are you seeing any early signs of the mean starting to revert?

AR: In 2018 we owned companies at 10x P/Es that normally trade at 10-15x, which then ended the year trading at only 7x. A lot of that seems to be the market dynamic, where the fascination with large-cap tech and growth companies has been sucking the wind out of the types of value stocks we favor.

We've seen this before, and we've seen a rotation that follows that works very much to our advantage. Hope is not a strategy, of course, but we're quite comfortable owning the names we do at the valuations at which they trade. Our opportunity set is cheaper today than it was in early 2000, the last time we saw a massive rotation out of growth and into value. I've learned not to speak or think in absolutes, but I believe something like that is likely to occur at some point, ideally sooner rather than later.