Dan Davidowitz Polen Glenn Welling Engaged Christopher Chris Kiper Legion Adam Schwartz Sean Huang FM First Manhattan China Anhui Gujing Central China Real Estate Gartner Hain Celestial Primo Water PRMW Rent Center RCII SVMK Survey Monkey Alphabet GOOG Facebook FB Align ALGN Del Friscos Aarons AAN BAIC

Your performance has stood out positively during the long bull market as much as any investor we’ve spoken with [VII, June 30, 2017]. Are you concerned that times are about to get tougher?

Dan Davidowitz: We certainly think about that. The S&P 500 trades at roughly 17x forward earnings, a premium to its long-term average of 15x. Our Focus Growth portfolio, which normally trades at a 30-50% premium to the S&P 500, is now at the high end of that range. If I were forced to guess I would say it probably feels more near the end than the beginning.

But there’s really nothing scientific behind that. The only logic there is that we’re 11 years into a bull market and valuations will eventually return to their historical averages. I can’t argue with that, but it doesn’t really tell us much more than that. All it really says is that this bull market has been longer than usual.

We don’t make economic or market predictions because we don’t feel we can do so accurately or consistently. But we do have a view on what valuations should be for our companies, which depends a lot on the level of interest rates. Our assumption has been that the five-year risk-free annual rate should “normally” be around 5% – using the historical average yield on five-year U.S. Treasury notes, which matches our average holding period. But over the past 20 years the yield on the five-year note has been above 5% for only one of those years, 2006. The yield now is 1.4%.

If rates below 4% turn out to be closer to the sustainable number over the next five to ten years, you can make a plausible case that valuations today should be higher than they are now. We think the market today is baking in roughly 4% rates for the coming five to ten years, which seems plausible for a number of demographic and macroeconomic reasons.

But the reality is we’re not making that call one way or the other. What we are doing is what we’ve always done: trying to identify companies that primarily through earnings growth can generate double-digit annual shareholder returns. In fact, since 1989 our portfolio’s annualized gross return has almost exactly matched the 15% annual earnings per share growth our portfolio companies have achieved on a weighted-average basis.

Are you finding good ideas harder to come by today?

DD: It feels kind of normal. Valuation is a bit more of a hindrance on the most interesting names, but we’re patient and with the volatility of late, the prices for some of those names are starting to come closer to where we’d like.

We always own a balance of higher-growth and more stable-growth companies, and I’d argue today that the safer names are relatively more expensive. The faster-growth companies have higher absolute multiples, but we sometimes don’t believe those multiples show an appreciation for how fast and how long we think they can grow.

We’d put Facebook [FB] and Alphabet [GOOG] in that category today. A key concern is the potential for increased government regulation of the big technology companies and the possibility of antitrust action. But it’s very hard for us to see anything happening that seriously damages the competitive advantage or the growth profile of either company. The secular tailwind from digital advertising still has a long way to go globally. Both companies distribute their products for free to consumers, so it strikes us as very hard to conclude that those consumers are being harmed. Judging by their behavior, both consumers and paying advertisers seem to indicate they’re being well served.

No one would argue these aren’t super-high-quality companies, but we just find the multiples on their stocks – in the low-20s on forward earnings – to be very low given their competitive advantages and the fact we think each can generate at least mid-teens earnings per share growth over the next five years. Valuations get cheap in a hurry with that kind of compounding.

What do you think the market is missing in Gartner [IT], another of your technology names?

DD: Gartner is a technology research company, with 10,000 analysts who basically know everything about every technology vendor and every software, hardware or services offering you could possibly buy. Customers are typically large corporations spending $10 million per year or more on technology, who need someone like Gartner to consult with them and give them guidance on what’s out there and what’s coming down the pike. If we’re upgrading our customer relationship management system, for example, they’ll help us with things like the best offerings for asset managers, what competitors are using, the advantages and disadvantages of different systems and approaches, and what pricing and terms should be.

It’s a highly recurring subscription business. For a standard subscription with access to research and analyst support, you’ll pay something on the order of $50,000 a year, less than 1% of your technology spend. Client retention is in the low-80% range per year, with wallet retention – spending from existing clients – at over 100%. They’re able to increase prices 3-5% per year.

The core business is growing at a low- to mid-teens annual rate and we expect that to continue for a very long time. Technology is not getting any simpler, easier to understand or less important. It’s crucial to everything, so it’s not just the IT department making choices today, it’s the chief marketing officer, the head of legal, the head of HR, even the CEO.

We also consider the market underpenetrated. Gartner now has 15,000 clients and they believe the addressable market worldwide is over 100,000. Usually the gating factor is that they can’t hire salespeople fast enough to reach all the organizations that might benefit from their services. It’s a consultative sell, so it takes time to build out the sales force and to bring on a new client. But as I mentioned, once they’re on board they tend to stay.

The competitive environment?

DD: There’s really no natural competition. IDC is a smaller, niche player, but Gartner is really the gold standard. If Nike’s Chief Technology Officer is going to the board to choose a cloud provider, Gartner’s seal of approval is what you want.

We subscribe to Gartner ourselves, because we use their analysts when we’re researching technology companies. Technology vendors sometimes criticize Gartner’s view on things because their analysts don’t mince words and they say what they really think. Of course from a client perspective that’s exactly what you want to hear. They have a reputation for not playing favorites and giving an honest assessment on all things technology. That independence makes people want to work with them.

The company diversified somewhat at the beginning of 2017 in buying CEB Inc. (formerly Corporate Executive Board) for $3.3 billion. Has that paid off as expected?

DD: The idea behind the acquisition was to expand into providing similar best-practices types of insights in a variety of non-technology areas, including operations, finance, legal, human resources and a number of other vertical disciplines. With technology increasingly impacting everything, they saw benefit of having more direct access to other parts of the enterprise. They also thought CEB wasn’t run as well as it could be and that applying Gartner’s discipline and processes would improve the business.

While the strategic rationale made some sense, the deal also brought risk. It was a $3.3 billion acquisition when Gartner’s market value at the time was around $10 billion. That added leverage, which we don’t like, brought on incremental execution risk, and was a potential distraction from this awesome technology business growing beautifully at very high margins.

So far the improvement of CEB, now rebranded as Gartner Business Sales, has been slower and has required more investment than expected. That larger investment has been a drag on overall EPS growth. The company argues that the GBS business is at an inflection point where the customer attrition is improving and the business can soon start growing at a double-digit rate as they have moved away from enterprise licenses to a more recurring seat-subscription model. It doesn’t take heroic assumptions to see the GBS business getting back to acceptable growth in the near term, but we also don’t think it has to happen for the company overall to do well. GBS only makes up about 15% of total revenues and they won’t keep throwing money at it if it doesn’t produce. If it does, that’s great, if it doesn’t, it becomes a smaller problem every day.

From today’s price of just under $132, how are you looking at upside for Gartner's shares?

DD: The stock trades at a mid-20s multiple on the next 12 months estimated free cash flow of around $5 per share. We consider that perfectly reasonable for a company we believe can compound free cash flow at a mid-teens rate. Even if the addressable market is only half what Gartner thinks it is, it’s still 3-4x what it is today, and there isn’t much competition. We like that we don’t have to be very precise on the ultimate addressable market and can still see a very long runway for growth.

We spoke last time about Align Technology [ALGN], whose stock has been on quite a ride since. From just under $150 in mid-2017, it hit $400 in September of last year, but now trades at around $180. Can you update your view on it?

DD: This is an interesting situation because the company is essentially creating the market for clear aligners that can replace traditional braces for straightening teeth. In these cases you often get a lot of volatility as the market constantly tries to size the opportunity and evaluate the extent of the competition. We knew it wasn’t going to be a straight line along the way.

We tend not to trade our stocks too much, but with this one we’ve been a bit more active because of how large the swings have been. We first bought in at around $70 and have since bought at under $100 a couple of times and trimmed north of $300 a few times. It's currently a 2% weighting in the portfolio.

We still very much like the opportunity. Even with what are perceived as hiccups now and then, the company is still growing at a better than 20% annual rate and we don’t expect that to slow down for a long time. Our view is that if braces didn’t exist today and all of the sudden people came out with two inventions to fix crooked teeth, one of which was braces and the other of which was clear aligners, nobody would use braces. It’s an archaic, barbaric way of straightening teeth. We believe over time the entire market shifts from braces to clear aligners. We also think the number of case starts for teeth correction will at least double over the next ten years.

That means that the potential addressable market is more than 10x its current size, so you can assume plenty of competition – that Align only gets 50% of the market at maturity, from about 90% today – and still see this as a very attractive long-term growth opportunity. The volatility of the stock we think has been out of line with what will turn out to be the volatility of the business.

Your strategy has protected capital remarkably well in downturns, with a “downside capture” percentage over more than 30 years in the mid-50% range. To what do you attribute that?

DD: We try to own companies with pristine balance sheets and tons of free cash flow – so competitively advantaged and not at all dependent on capital markets – with earnings growth that’s very resilient. Our portfolio on a weighted-average basis has never had an annual earnings decline. Through the 2008 financial crisis we still had double-digit earnings growth in our holdings. If the earnings keep growing, a stock can’t go down that much for that long before it gets really cheap. It also helps that we always have a balance between higher-growth and more stable growth names. Companies like Oracle and Accenture and Dollar General that crank out 10-11% earnings growth over a long period of time with extreme consistency tend to hold up relatively well when the market is in decline.

We’ve thought a lot about whether the change in market structure we’ve seen – with the significant rise in trading by non-people – could make it harder for us to outperform in the next down market. It is possible that correlations may be a lot higher as all these momentum and passive strategies trade in the same direction.

We still believe, however, that if we own fundamentally better businesses with persistent earnings growth, we should perform better than the broader market regardless of the economic environment. Our advantage may not be as high in the immediacy of a drawdown, but if we’re true to our strategy and execute it well, over the full course of a market break we should still better than hold our own.

What’s the business case for an investing strategy like yours in today’s market?

Glenn Welling: We’d argue ours is an all-seasons type of strategy. We focus on small to mid-cap companies that because of self-inflicted missteps are underperforming their peers and have stocks that trade at a significant discount relative to their potential. We’ve found the available supply of such companies to be fairly consistent over time, and given how we invest, we only need two or three new ideas a year.

I would say, though, that we can have an advantage in markets that lack direction or are more challenged because we take it as our responsibility to manufacture our own returns. That stands out less when stocks just keep going up year in and year out as they mostly have for the past ten years.

I also believe a case can be made for an activist strategy depending on where you think we are on the growth versus value spectrum. Growth investing has been beating value investing for years now and that’s been a headwind for activism, which is without a doubt a value or even a deep-value strategy. If you think, as I do, that we may be close to a reversion point where growth steps aside and value ascends, activism is arguably a good place for your money.

You’ve described investing in more opportunistic shorter-term ideas as well as longer-term turnarounds. What’s the mix in your portfolio today?

GW: We always try to have roughly 20% of the portfolio in opportunistic ideas where we see a shorter-term catalyst, often involving some sort of M&A. A good example that recently worked out was our investment in Del Frisco’s Restaurant Group, which over the summer was bought out by the private equity firm L Catterton. Done well, those generate good returns in shorter periods of time and free up capital to invest in new ideas or to add to existing ones.

The vast majority of our holdings are longer-term turnarounds that typically take two to four years to play out. At this point in the market cycle to get the discounts to intrinsic value we’re looking for we probably focus a bit more on longer-term, somewhat hairier turnarounds. That said, we love our existing portfolio, which is where we’re spending most of our time and which we think has as much or more inherent upside than at any time in years past. Given our conviction in our top names, we’re more concentrated as a fund than we’ve ever been.

Let’s talk in more detail about your two top holdings, starting with consumer-foods company Hain Celestial [HAIN].

GW: Hain was one of the pioneers in the natural and organic food industry, building through acquisition over the last 20 years a large portfolio of some 55 brands across numerous categories. It was a roll-up strategy, which to be successful requires buying the right assets at the right price, integrating them well to get all the benefits of having them under one roof, and then leveraging that scale to innovate and organically grow.

Hain’s focus was on acquiring relevant businesses at the right price, but it fell awfully short on the integration and innovation fronts. As the natural and organic foods business became more mainstream and competition picked up, the company wasn’t able to maintain its competitive advantage from being early. That’s when we identified it as an opportunity. It was right down the middle of the fairway of what we look for: a good business with industry tailwinds, trading at a significant discount to its potential, where we thought we could be the catalyst to drive the strategic, operational, organizational and financial changes that were needed. We stepped in starting in the third quarter of 2017.

What are the basic elements of the turnaround strategy?

GW: We early on settled with the company to change a majority of the board. It’s kind of hard to believe, but no outside directors had any experience in consumer products or the food industry. In addition to bringing in new directors with relevant experience, last November the founder and long-time CEO was replaced by Mark Schiller, who had most recently been the chief commercial officer at Pinnacle Foods. Pinnacle had gone through a very similar turnaround prior to a successful sale to Conagra.

The company at an investor day in February laid out its new strategy, with four key pillars. The first is to simplify the business, focusing only on the categories and brands that are growing and where they believe they have a right to win. The focus of attention and dollars will now primarily be on five categories – snacks, tea, personal care, yogurt and baby products – and a dozen key brands.

The second pillar is to strengthen capabilities. This is an operational turnaround, so operators with track records of success in the food industry need to be in the key positions. Mark has replaced all but two of his 10 or so direct reports in the past nine months.

The third focus is on expanding margins and cash flow. A lot of this is blocking and tackling, like making the supply chain more efficient, integrating functions that never really were integrated, and improving working-capital management. Some of all this is starting to show – adjusted EBITDA margins have increased sequentially for the past three quarters and are up over 400 basis points this year, from 6% to over 10% in the most recent quarter. We expect margins to continue to improve – management’s target is for 13-16% EBITDA margins, with the “get bigger” brands doing even better than that.

Finally, the company is focused on reinvigorating profitable top-line growth in the core brands. The get-bigger brands receiving the most attention and investment are Terra Chips and Sensible Portions in snacks, Celestial Seasonings in tea, Alba Botanica, Avalon Organics and Jason in personal care, The Greek Gods in yogurt and Earth’s Best in baby food. These brands are expected to form the foundation of the future Hain.

The market doesn’t seem to have totally bought in yet. What upside do you see from today’s $19 share price?

GW: A good guidepoint to that question is to look at the longer-term targets in the new executive compensation plan. One of the most important things we can do in any potential turnaround is to align management’s pay with what drives shareholder value. That was a lesson learned very early in my career, that people do what they get paid to do.

We created a private equity type comp plan for the management team, in which all senior executives received a front-loaded grant of three years’ worth of equity when they arrived. Unless the team delivers a 15% annual total shareholder return from the CEO’s start date, none of that equity pays out. The threshold for management to receive the long-term equity awards at the end of 2021 is $39.74. That’s a pretty good indicator of what we believe is possible if the business grows on the top line at the 3-6% annual target, EBITDA margins continue to expand, and the market starts to believe in the turnaround.

ON INCENTIVES:

One of the most important things we can do is align management's pay with what drives shareholder value.

One big issue today for management is having to overcome a significant credibility gap with investors because of prior management. You do that by being transparent, setting expectations and then meeting or beating those expectations consistently. We’re confident that’s exactly what’s going to happen. Our conviction is extremely high – we nearly doubled our investment earlier this year and we now own just over 20% of the company.

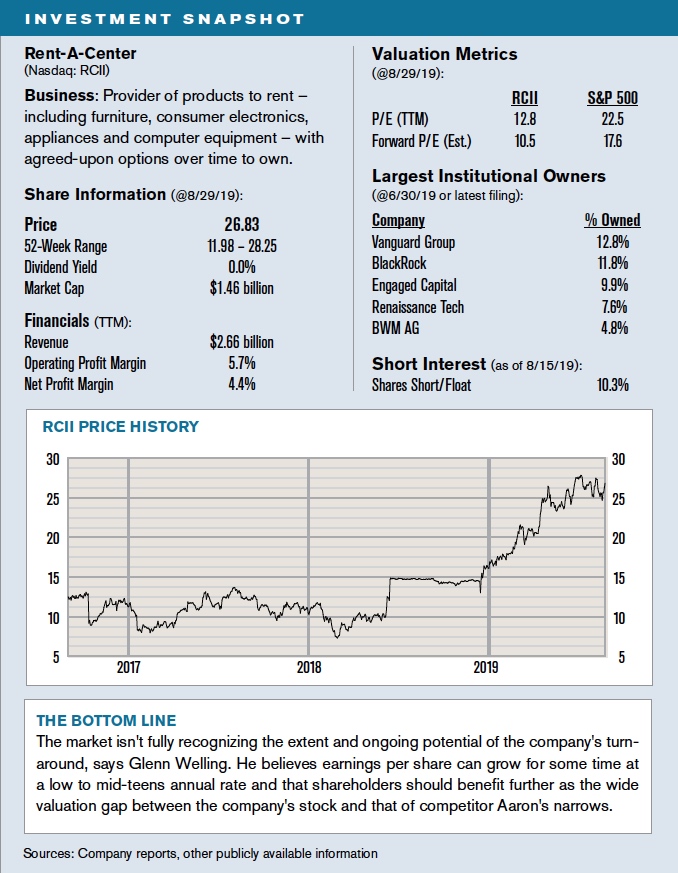

Rent-A-Center [RCII] would seem to be further along in its rejuvenation. Describe the potential you see for it from here.

GW: This is a rent-to-own business, providing primarily furniture, appliances and electronics to customers with sub-550 credit scores. They have their own brick-and-mortar retail stores, they have franchised stores, and they’re building out a very interesting line offering a rental option at third-party retailers like Ashley HomeStores.

We think this is a good, if somewhat misunderstood, business. There are only two national competitors – Rent-A-Center and Aaron’s [AAN] – and we don’t believe they face either the disruption risks of a traditional retailer or the credit risks of a traditional subprime lender. Their target customer has bad credit and in most cases doesn’t have a credit card, so often needs a rent-to-own payment option to get access to the household items they want. Rent-A-Center maintains ownership of the assets and takes them back if customers fall behind on their payments. The company has been doing this for a long time and has both the logistics systems and the collections operations in place – neither of which are easy to replicate – to handle the unique needs of the business. We think the competitive barriers are high.

Are there secular tailwinds behind this business?

GW: One thing we like in general is that it’s counter cyclical. When credit is easy and cheap, the core Rent-A-Center customer is better able to get credit and doesn’t need as much the rent-to-own option. As credit tightens and becomes more expensive – which is happening in auto lending already – those customers come back to rent-to-own rather rapidly. We think it’s a pretty good time to own a business that is a hedge against tightening credit.

The growth driver is in partnering with third-party retailers to offer a rent-to-own option. This is in its early days, but we believe it has the potential to significantly broaden Rent-A-Center’s addressable market. Their biggest partnership today is with Ashley for furniture. Aaron’s has a deal with Best Buy for electronics and appliances. Brick-and-mortar retailers are increasingly open to new ways of selling with a variety of new partners. We think this particular option has a long growth runway and there are only two self-funding national players to support it.

One initiative of the company’s board after Engaged got involved was to pursue “strategic alternatives.” Last June the company announced it was being sold to Vintage Capital for $15 per share, but the deal fell apart in December. What happened there?

GW: The simple answer is that Mitchell Fadel – who had been at the company, left to take another job, and then we brought back as CEO at the beginning of last year – had done a phenomenal job in turning the business around. In this case there was a heavy emphasis on cutting a bloated cost structure and streamlining decision-making. With the sale transaction bogged down in the regulatory approval process, the board had an opportunity to terminate the transaction, which they did given their belief that the offer price no longer compensated shareholders for the improved performance of the business. It became pretty clear that shareholders felt the same way, as the stock has increased in value from around $14 at the time to the high-$20s today.

Do you think the market is still missing something?

GW: This has been a very impressive turnaround that is still ongoing. In 2017 the company generated $71 million in EBITDA, but this year that will be north of $250 million. At the end of 2017 the balance sheet was 8.5x levered, but at the end of 2019 it will be less than 1x levered. Despite the company firing on all cylinders and the risk profile being significantly reduced, the stock still trades at big multiple discount to Aaron’s. On 2019 numbers, Rent-A-Center’s shares trade at slightly above 6x EV/EBITDA, while Aaron’s is trading at above 10x. On P/E, Rent-A-Center on this year’s numbers is at 11.5x, while Aaron’s is over 16x. Each multiple turn is roughly worth about $5 per share, so just from a more reasonable valuation we think there’s well over 50% appreciation potential in the stock. On top of that, as same-store-sales improve, margins improve and the growth in third-party partnerships kicks in, we think earnings per share can grow for some time at least at a low to mid-teens annual rate.

We’ve also added to this position as our experience with the company has gone on. Our initial purchases in late 2016 and early 2017 were at around $10 per share. We were happy the deal didn’t get consummated at $15, and ended up tripling our investment at $18. And we still think the share price grossly undervalues the asset.

Does whether we’re at a late or early stage in a market cycle have much impact on your ability to find good activist investment ideas?

Chris Kiper: It really doesn’t. There never seems to be a lack of companies that are underperforming for one reason or another and could benefit from activist intervention. A typical situation for us would be a company with a market cap between $250 million and $5 billion that has seen its stock decline by 50% or more over the prior 12 months for reasons we believe are fixable and where we believe our involvement can help. That’s been as likely to occur when the market is high as when the market is low.

Our opportunities typically involve companies going through a transition. Everyone can screen for stocks that are cheap on headline numbers, but what’s less visible to the algorithms is when a traditional business is just starting to give way to a new one, or a business model is changing for the better, or an acquisition is finally starting to pay off. You have to read the 10-Ks and proxy statements, dig through the investor presentations, and talk to management, competitors and experts in the industry to really understand what’s happening. That continues to be our prime fishing ground and, again, it seems as well-stocked with ideas as ever.

It should be a positive for our business if investors increasingly conclude that equity markets are poised to not go up very much over the next several years. One family office we spoke with recently told us they were expecting no better than 5% average annual equity gains over the next five years. A strategy like ours where we act as our own catalyst – assuming of course that the catalysts we pursue are the right answers for the business – should be able to unlock a lot more value than that.

Do you find the trade conflicts today opening or closing potential opportunities?

CK: We are seeing in general what seem to be more dramatic short-term reactions to companies with bad news and that miss numbers. That’s particularly true of companies sourcing their products from China. We’ve been looking at a lot of consumer-goods companies in that situation and think in many cases the near-term reaction is quite a bit overdone relative to the long-term impact. If the trade war with China gets worse, while it will take some time, companies will adjust their supply chains. If the trade war with China gets better, things will return more to normal. When the market reaction seems to price in negative news unreasonably far into the future, we think that’s opening up a number of potential opportunities.

Why do you see prospects turning up for portfolio holding Primo Water [PRMW]?

CK: The company has dominant market shares in its three businesses. The first is a water vending business, where customers pay roughly 35 cents a gallon to refill their own containers with purified water from large Primo-owned vending machines. They have 90% market share in this business, with 23,000 of these machines mostly stationed in front of convenience stores and supermarkets across the U.S., but more prevalent in southern and western states.

The next big unit is an exchange water business, where people bring their empty five-gallon containers to one of nearly 13,000 locations in the U.S. – also typically at high-traffic retail locations – and exchange them for already-filled containers to take home. The cost for this is about $1.25 per gallon and Primo controls about 90% of the market.

The final business is selling water dispensers that run the gamut from $10 basic pumps to $300 dispensers with hot and cold water, coffee makers and maybe even a pet drinking bowl at the bottom. Key retail partners in this business are Home Depot, Walmart and Lowe’s, and while selling dispensers at the moment doesn’t make a lot of money, Primo dispensers are in 8,700 locations and have about a 70% market share.

One important aspect of our thesis is that the company is on the right side of current consumer preferences. The demand for clean, purified water is still growing. Only recently in the United States has consumption of water on a per-capita basis overtaken consumption of carbonated soft drinks. At the same time, people are increasingly concerned about the environmental impact of individual-use plastic water bottles and are looking for the types of alternatives Primo provides. We don’t see either the health-related or environmental drivers of the business letting up any time soon.

We also see significant room for operating improvement. The company today is the result of a merger at the end of 2016 that combined Primo’s core exchange water business with the refill business of Glacier Water. At the time, management played up the potential to cross-sell locations. There wasn’t much overlap in the location footprint, and there was perceived to be a lot of opportunity to generate incremental revenue and make the distribution operation more efficient. They’ve executed on precious little of that so far, which is something we’re pushing them hard on to rectify.

On top of that we think there’s considerable potential to expand the number of locations and to institute price increases. The company’s products and services today are sold in 45,000 total locations, and management his said they think the addressable market is ultimately closer to 250,000. On pricing, as demand for purified water increases and single-use bottles fall further out of favor, Primo should have some ability to charge higher prices – especially on the refill side of the business – while still remaining quite cost competitive with alternatives.

How do you see all this translating to upside for the stock from today’s price of around $12.20?

CK: The company's latest projections for the current year are $315 million in revenue and $57 million of EBITDA. Net debt is just under $190 million, which results in an enterprise value today of $650 million. That values the stock at around 11.5x EV/EBITDA.

With healthy end-user demand, better pricing and expanded distribution, we think the company can increase its top line at 6-9% per year. EBITDA margins, around 18% today, we believe within five years can be 22-23%. Three to four years out the company can be debt free through the use of cash flows shielded by a substantial tax-loss balance. All that would translate into something on the order of $100 million in EBITDA five years out. Put a peer 14x EV/EBITDA multiple on that and we think over that time this could be a $40 stock.

We recently filed that we’d taken our ownership in the company to 9.1% of the shares outstanding. We believe this should be a multi-year compounder and expect to be very active with the board and the management team to deliver on that promise.

Describe the positive transition you believe is underway at SVMK Inc. [SVMK], the parent company of SurveyMonkey.

Sagar Gupta: This is an online-survey company that provides what it calls “experience management solutions” that help organizations engage with and solicit feedback from their customers and employees. The idea is that in addition to seeing what people are doing, SurveyMonkey provides the tools to help you understand why they’re doing it as well.

The transition involves the company’s recent investment in building out a suite of enterprise-grade solutions and the expansion of its sales force to cultivate the top 10% of the heaviest users. The platform has been naturally viral in that people get exposed to quick surveys and then some percentage go on to use them in their own work. That’s driven significant organic growth – there are now more than 17 million registered users on the platform – at very low cost. Most upgrades to paid services, which generate run-rate annual revenues today of $300 million, have been user initiated and done online. The sales force is meant to engage the biggest users now and upgrade them to even more valuable offerings.

We think the secular tailwinds behind experience management solutions are quite significant. Given the choices customers have to find and buy almost anything, there’s a higher premium than ever on understanding what people want and getting the customer experience right. We’ve seen research from PwC that says that 32% of all customers will walk away from a brand they love after just one bad experience.

We actually as a firm have an annual subscription plan with SurveyMonkey that we use for market research. It has built a consumer panel of two million people that subscribers can access on a per-usage basis. For example, we did a survey of 650 Bed Bath & Beyond customers when we were doing due diligence on the company. We ended up getting a lot of valuable insight at a cost of a few thousand bucks. Had we hired a consultant or traditional research firm to do pretty much the same thing it probably would have cost $50,000.

On the employee-engagement side, the cost of employee turnover is a long-standing and increasing problem. One representative example the company cites for how their products can help address that is a program they did with Celadon, a truckload shipper based in Indianapolis. Celadon had an issue with drivers leaving within the first 90 days of employment. Working with SurveyMonkey, they automated driver feedback collection as new drivers came on board and following up at 30, 60 and 90 day intervals. Problems were heard and actively followed up on right away. The company credits the program with helping improve driver retention by nearly 70% in the first year, with a significant positive impact on profitability.

What’s your activist agenda here?

SG: We’d like to see the company improve its financial disclosure – in particular on the economics of the user base as it transitions from free to low-tier to enterprise – and be more proactive in general with its investor base. We also want them to think more about developing strategic relationships with the other large tech platforms. They do some of that today, but as an example we could imagine that a broader partnership with a social network like LinkedIn and its over 500 million users would generate significant mutual benefit. As is often the case, there are also some governance and compensation changes we recommend. One would be that they do away with staggered board membership and elect all directors annually.

With the shares at a recent $17.10, how are you looking at valuation?

SG: If enterprise sales continue to ramp up as we expect, we think this goes from a relatively low-growth company to one that can generate 25% or so annual top-line growth for some time. We estimate free cash flow margins by next year will be roughly 20%, and there should be operating leverage in the model from there as average ticket sizes increase. To give a sense of the potential upside, SurveyMonkey’s current average annual revenue per enterprise user today is around $9,000. For direct competitor Qualtrics – which SAP within the past year acquired for $8 billion in cash – that number is closer to $40,000.

What’s a business with this growth profile worth? The stock today trades for around 6.5x forward consensus revenues. Recent IPOs like Slack Technologies and Zoom Video go for 20-30x forward revenues, and while those companies may be growing somewhat faster than SVMK, they’re following the same basic go-to-market strategy in upselling organic and viral in-bound customers to more lucrative paid plans. This “self-serve” dynamic within the SaaS has enabled high growth at enviable profit margins, hence the high multiples. SAP paid 14x revenues for Qualtrics. Even if we use 10x revenue on our estimate of 2020 sales for SVMK, this would be a $30 stock.

Do you think the company is likely to eventually be sold?

SG: Salesforce bought shares in SVMK at the IPO and recently increased its stake. We can’t imagine Oracle didn’t take notice of SAP’s purchase of Qualtrics. And Microsoft is a close partner today. We certainly believe the company has a viable strategy to go it alone, but we also think it has a tremendous amount of strategic value and would therefore make a very attractive sale candidate.

The macro environment around investing in China has changed a bit since we last spoke [VII, February 29, 2016]. Have you changed anything in your approach as a result?

The macro environment around investing in China has changed a bit since we last spoke [VII, February 29, 2016]. Have you changed anything in your approach as a result?

Sean Huang: We can’t ignore the big macro headline issues, but we try very hard to do so. The biggest growth engine for China and the biggest opportunity for the fund has always been the growing Chinese middle class, which now numbers around 300 million and we think can continue to grow for a long time. Our portfolio today has no exporters, and consists entirely of domestic Chinese companies that offer products and services for Chinese consumers. We understand that trade relations with the U.S. are very important and can impact at times Chinese consumers ability to consume, but the long-term dynamics we’re focused on haven’t changed in any material way.

The macroeconomic environment has weighed on valuations in Chinese markets. Hong Kong’s Hang Seng Index companies trade at a trailing price/earnings ratio of around 10x today, versus the ten-year average of 12x. The weighted average P/E ratio on 2019 estimates for our portfolio is now only 6.5x, for companies that average a return on equity of nearly 20%. We believe we are investing today on attractive terms.

Adam Schwartz: What we saw as an opportunity when we started the fund in China 10 years ago was that doing the detailed, labor-intensive research we’d done for 45 years in the U.S. had a good chance of paying off in a market that’s less efficient for structural reasons like strict capital controls, the difficulty in getting information and the lack of professional investors. Our going-in thesis for local, research-driven value investing hasn’t changed at all and we think it’s the reason we’ve had the success we have.

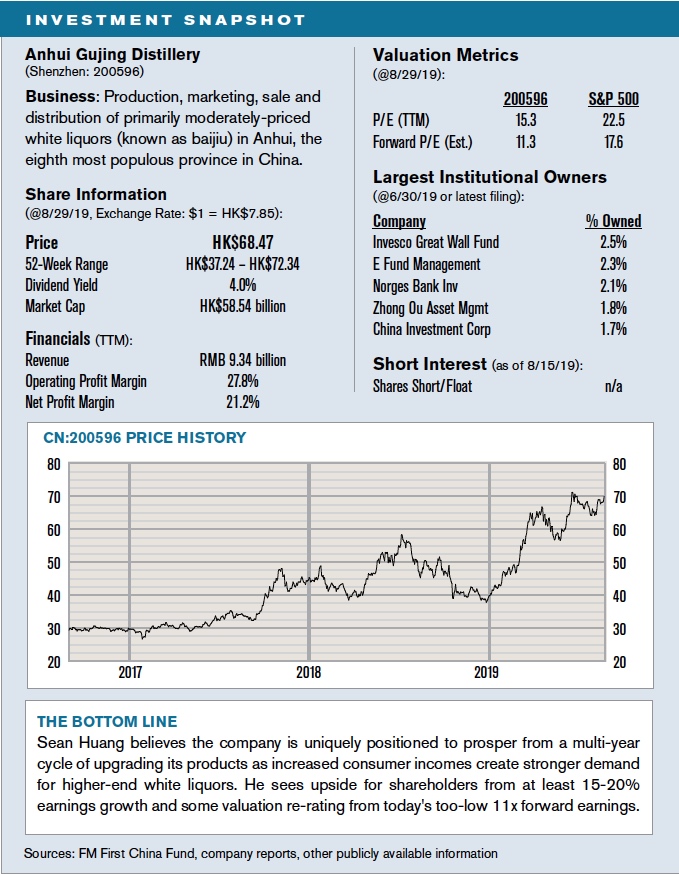

In what ways is Anhui Gujing Distillery [Shenzhen: 200596] representative of the type of opportunity that attracts you?

SH: Anhui Gujing is one of many publicly traded makers of so-called white liquor in China, with the most popular brand in the central inland province of Anhui, where the company generates roughly 90% of its revenues. The brand’s origins go back something like 1,800 years, and the company benefits from a uniquely broad and deep sales and distribution effort in the province.

The basic story here is that this is a well-established brand that is in a multi-year cycle of upgrading its products as increased consumer disposable incomes create strong demand for higher-end white liquors. The significant majority of the company’s revenues today come from products priced below 200 renminbi per 500 milliliters, but that mix is shifting as it rolls out new products like Vintage 8, which costs essentially the same to make but sells for 2-3x the price of the traditional products. (For comparison, big-name competing brands like Maotai sell for closer to 2,000 RMB.) As volumes and average selling prices go up, we think it’s reasonable to expect the company to compound earnings at a 15-20% annual rate for at least the next few years.

One unusual aspect of investing in this company is the difference in valuation between the A shares and the B shares, which is what we own. B shares were originally created for foreign investors who wanted to invest in China but were prohibited from owning A shares. Some of those prohibitions no longer exist, so B shares have faded somewhat in investor interest. But they still have the same voting and economic rights as A shares, so can be quite interesting when they trade at a significant discount just for liquidity reasons. Anhui’s B shares, for example, currently trade at just 14x estimated 2019 earnings, versus 26x for the A shares. Discounts that big usually don’t last, and there is a possibility the company could convert B shares to A shares, which would eliminate the discount altogether.

With the B shares currently at HK$68.50, how are you looking at upside?

SH: Peer white-liquor companies typically trade at 25x-plus P/Es, so we think there’s plenty of opportunity for valuation improvement from today’s 15.5x multiple on 2019 estimates and 11x P/E on 2020 estimates. But we don’t need the multiple to expand to do well with a company we think can grow earnings at 15-20% per year. On top of that the company pays approximately 40% of its profits out in cash dividends and the stock currently has a 4% yield.

AS: This is pretty representative of the type of company we focus on. The market cap is between $5 and $10 billion. We believe it operates in a good industry that is fairly easy to understand. We’re also not going for the biggest-name player like Kweichow Moutai [Shanghai: 600519], which makes Maotai and has a market capitalization of over $175 billion and trades at a P/E multiple of 25x next year’s earnings. We’re playing in a company that is much smaller, growing faster, and trading at less than half the valuation multiple. We think it’s a much better and safer long-term bet.

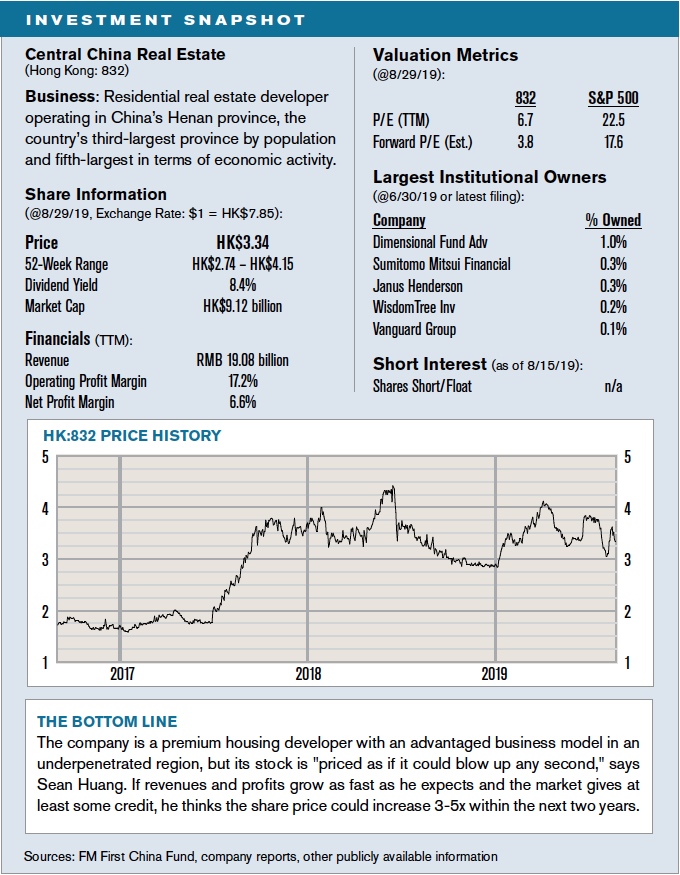

From white liquor to residential property development, describe your investment case for Central China Real Estate [Hong Kong: 832].

AS: Western investors are aware of a number of pretty well-known consumption-upgrade stories in China, usually having to do with what people eat and what they wear. But one of the biggest upgrade stories that we believe gets much less attention is the movement from sub-standard housing to middle-class housing. That’s the trend behind our interest in Central China Real Estate.

SH: The company focuses almost exclusively on developing homes in Henan province, which is China’s third most populous province and is located within a three-hour train ride to 60% of the country’s population. It’s one of the few home developers we’ve come across with a strong enough brand to command a 10-15% pricing premium versus other local or national players. That should be valuable as it looks to build market share in a so-far underpenetrated market, where the 48% urbanization rate is 10 percentage points lower than the national average.

In addition to expecting the company to incrementally benefit as more people with greater spending power look to upgrade their housing in Henan, we also like that management has been shifting to more of an asset-light business model. They increasingly partner with local investors who come up with the capital and take the financial risk of a development, while Central China is paid to license its brand name, build out the property, and then often manage and maintain it going forward. Both the traditional and asset-light sides of the business are growing nicely, but the mix has shifted to where now close to one-third of the business follows this asset-light model, which is very profitable and should continue to grow as a percentage of the total.

Hearing the words “China” and “real estate” together might give a U.S. investor some pause. How do you handicap any bubble-like risks here?

SH: The key for us is the urbanization rate. If you study real estate markets around the world, crises don’t tend to happen until urbanization rates go above 70%. Henan’s levels are far from that and housing prices in the region have stayed much lower overall than in the coastal cities. Central China projects on a price per square meter basis are only one-third as high as in first-tier cities like Beijing and Shanghai.

How cheap do you consider the shares at a recent 3.35 Hong Kong dollars?

SH: Consensus earnings estimates for 2020 are 84 cents a share, resulting in a forward P/E today of 4x. Using our estimate of cash earnings – the company takes in cash faster than they report it according to International Financial Reporting Standards – the P/E is more like 2x.

We think the company can increase earnings by 50% per year for the next three years. For a premium developer in an attractive province with an advantaged business model, that should eventually deserve a historical industry-average P/E of 5-7x. The stock today is priced as if the company could blow up any second. We just don’t agree with that at all. We really believe the share price could appreciate at least 3-5x over the next year or two.

One other thing worth pointing out is that the company’s chairman, Po Sum Wu, in July spent on the order of HK$2.8 billion to purchase an additional 23% stake in the company at HK$4.30 per share. We think that investors are able to buy shares at 20% less than the price a knowledgeable insider paid only two months ago is an indication of how inexpensive the stock is.

You wrote recently about closing out your position in automaker BAIC Motors [Hong Kong: 1958]. What prompted that?

AS: We've gotten better in multi-year investments at recognizing and admitting when the data and facts indicate the situation has fundamentally changed. With BAIC, the company’s joint ventures in China with Mercedes-Benz and Hyundai have lived up to our expectations, but what we didn’t accurately handicap was management’s inability and unwillingness to address its money-losing domestic-brand business. This is a partly state-owned enterprise and we concluded that the leadership just wasn’t sufficiently profit oriented. A private owner would have moved more aggressively to stem losses in that business. With a concentrated portfolio – our top ten positions are close to 90% of total assets – we have to be diligent to make sure what we own is the highest and best use of capital. As we gained experience with BAIC, we concluded its stock wasn’t.

Would you like to take a stab at how the trade conflict works out?

AS: It’s healthy to recognize that it’s actually quite natural historically to have trade conflict between a rising global economic power and the stagnant-in-relative-terms incumbent. There’s going to be increasing friction and the relationship is going to have to be redefined. We want to believe, and do believe, that eventually the two sides will recognize that everyone benefits from global free trade, and that the sensitive issues relating to things like intellectual property and government interference with markets will get worked out over time. We just don’t know when or how.

SH: I would just add that this conflict is likely to be long and turbulent. It seems unlikely to me that one big agreement will solve everything, so we need to get accustomed to progress coming in fits and starts. To the extent that offers up investment opportunities, it’s up to us to take advantage.