Valley Forge Dev Kantesaria Moodys MCO Fair Isaac FICO Visa Intuit INTU Monster Equifax Experian TransUnion Alphabet Facebook Apple American Dairy Credit Ratings Mastercard TurboTax QuickBooks

It’s not uncommon today to hear investors say, as you do, that they want to own “the highest-quality businesses with strong organic growth, predictable earnings, capital efficiency and prudent management.” You’ve proven better than most at doing that well – elaborate on what you’re looking for and why.

Dev Kantesaria: Although many investors claim to invest in high-quality businesses, we find that very few of them actually focus on the right types of companies. We are looking for businesses with highly predictable and strongly growing earnings over the next 10-plus years, which is a very high bar.

Business quality to us incorporates many different things. First and foremost, we want an entrenched company that provides an essential service or product. That generally means it occupies the first or second position in its industry and, most importantly, it has pricing power. If you can raise your prices above the rate of inflation without affecting your unit volume, that’s a fantastic business.

We also like businesses that are scalable, have positive industry volume trends, and have margins that increase with each additional dollar of revenue. The cost structure should be flexible, without significant research and development or capital spending needed to keep the engine running. Earnings streams should be relatively predictable and not overly affected by macroeconomic or extraneous factors like commodity prices or interest rates.

Another important aspect of a high-quality business is capital efficiency. Almost all of our companies have a high return on tangible assets, which is one of Warren Buffett’s favorite metrics. We want to own businesses that don’t require the next Steve Jobs to run them, but management’s interests should be fully aligned with shareholders. Management should also have a strong and consistent record of using the free cash flow the company generates in a prudent manner, whether buying back stock, paying dividends or reinvesting in the business.

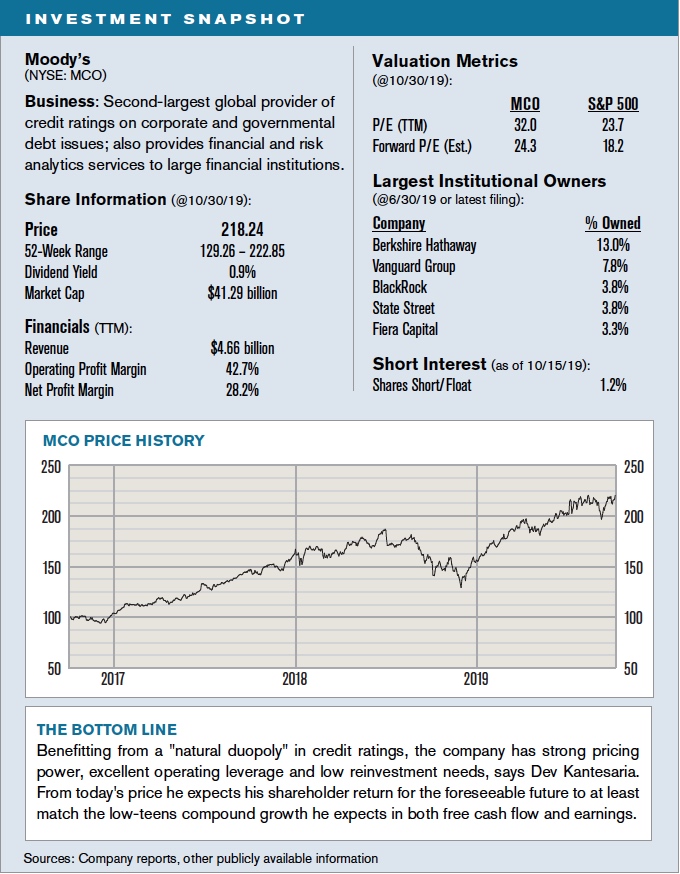

Moody’s [MCO], the credit-ratings company, is one of the best examples of the investment ideals we try to uphold. It operates in a natural duopoly with S&P Global [SPGI] in an industry with strong secular tailwinds. It has consistently strong pricing power, excellent operating leverage and low reinvestment needs, meaning most of its free cash flow is available for tuck-in acquisitions, buybacks and dividends. Moody’s is the toll collector on an increasingly busy global road.

We first bought into Moody’s during the 2008/2009 financial crisis when they couldn’t give the stock away. There was negative publicity – not undeserved – around ratings in a certain area of the debt market, mortgage-backed securities. There were regulatory threats coming from Congress and the SEC. There was significant litigation. The stock at the time traded at a single-digit P/E, which I remember was about the same multiple placed on Ford Motor. That sort of market disconnect doesn’t happen too often. That’s not to say there weren’t real issues to work through, but on balance we thought the situation provided an amazing entry point into what we expected to be a very healthy long-term business.

How do you define your opportunity set?

DK: We're agnostic to market cap, industry and geography and track a few hundred companies in industries with favorable dynamics. We have financial models built for about 100 companies at any given time, and the short list of those we’d like to buy is generally 15 to 20 names.

There are a handful of situations that can arise in a given year where a great business goes on sale. The price drop could be caused by a general market dislocation or by something specific to the company, whether it’s a bad earnings release, a heightened competitive threat, a regulatory issue, a legal issue, or sometimes just market neglect. The inefficiency in pricing can last for a day, a week or occasionally longer – which was the case with Moody’s – but usually it's relatively short-lived. Our job is to be prepared to take advantage when inefficiencies occur.

You mentioned what was happening in the case of Moody’s to make the stock mispriced. What’s another representative example?

DK: Another good one would be Monster Beverage [MNST]. We had followed the company for many years, and it had most of the characteristics we look for, including strong organic growth, high margins and pricing power. We were given the opportunity to build a position several years ago when news broke that reports were filed with the Food and Drug Administration on several deaths possibly linked to consumption of Monster Energy drinks. The news caused the stock to drop approximately 35% over just a few days.

We thought the market reaction was unwarranted. Over 10 billion cans of energy drinks had been sold over many decades, and we thought it would be unlikely for the ingredient at issue, caffeine, to become a regulated substance by the FDA. Having already done extensive work on the company, we built a roughly 10% portfolio position over just a few days. That particular inefficiency only lasted for a few weeks, until the FDA publicly expressed that it had no concerns about Monster’s products, and it’s been a very good story since then.

Do you still own it?

DK: In fact, we just sold it earlier this year. We still consider Monster an excellent business, but increased competition in the energy-drink space has reduced the company’s future pricing power and margin potential. We concluded that we had more compelling, higher-quality opportunities to invest in.

Was Equifax [EFX] another case where bad news, in this case its 2017 data breach, provided an entry point into the stock?

DK: It was. We think the credit-bureau industry, controlled by Equifax, Experian [London: EXPN] and TransUnion [TRU], has excellent growth and competitive dynamics that we don’t see changing for a very long time. As we looked at the possible legal liabilities for Equifax stemming from the breach – using comparable situations from the recent past – we thought the economic and legal issues were quite manageable relative to the earnings power and balance sheet of the company.

Do you still own this one?

DK: We sold it roughly a year ago, and as with Monster, our reason for selling was that we found a better opportunity. Our work on Equifax and the credit-bureau ecosystem led us to examine more closely Fair Isaac [FICO], which creates the models used to calculate consumer credit scores. Very few investors were paying attention to FICO’s plan to institute significant special price increases in many of its credit-score categories. At the same time, the company was restructuring its agreements with the credit bureaus in a way that would allow it to institute annual price increases in a uniform way. We thought these changes would lead to significant improvements in the profitability and sustainability of the business model, yet the market wasn’t giving them any credit for it. So, although we did well with Equifax, we decided this market neglect made Fair Isaac a better investment.

Let’s talk about some ideas that don’t make the cut, such as Alphabet [GOOG]. Where in your estimation does it fall short as a potential investment?

DK: Capital allocation, in general, is usually one of the highest hurdles for us to clear before making an investment. Google is an example of a company that has one of the best business models on the planet, but it uses a lot of its free cash flow to invest in peripheral businesses that historically haven’t had great returns on investment. Many appear to be pet projects of the founders, who because of a dual-class share structure are able to act without listening to shareholder input. They can hoard cash or make speculative investments and there’s not much their investors can do about it.

ON FAANGS:

We look for predictable and efficient uses of free cash flow – we don't see that in Google, Facebook or Apple.

We’re looking for predictable and efficient uses of free cash flow, and we just don’t see that in Google – or in Facebook or Apple for that matter. The arms race in capital expenditures and R&D spending by these companies has only intensified in recent years.

You spent a number of years as a healthcare venture capitalist. Why don’t you own any healthcare stocks?

DK: The short answer is that we simply don’t find the business models of hospitals, medical-device companies, biotech companies and pharma companies to be predictable enough over a 10-plus year time frame. That lack of long-term visibility makes the risk/reward proposition uninvestable for us.

You don’t appear to invest much outside the U.S. Why?

DK: We have invested in non-U.S. stocks, but I would say the capitalist ideals, reporting standards and capital-allocation decision making of U.S. companies are the best in the world. Foreign investments also have corporate-governance and political risks that are very difficult to factor into the price you’re willing to pay. We much prefer to get our international exposure through U.S. multinationals rather than buying foreign companies directly.

Has your view on the subject been informed by hard-earned experience?

DK: The most impactful loss in our fund’s history was in 2010, when we invested in a Chinese infant-formula company, American Dairy, that traded in the U.S. China is the largest infant-formula market in the world and we thought the company had a tremendous opportunity when a number of local competitors came under fire for using substandard and even dangerous substitute ingredients in their formulas. American Dairy’s stock got hit like the rest and traded down to a single-digit P/E multiple, but it actually had great sourcing from high-quality dairy farms, and we thought it would prosper in a growing, oligopolistic market alongside big foreign brands like Enfamil, Similac and Nestle.

Unfortunately, we got a number of things wrong. First, we entered the battle too early. Although the company had strong shares in second- and third-tier cities in China, the product landscape was still quite fragmented and it was difficult to pick the ultimate winners. Furthermore, we misjudged the extent to which mothers would switch to foreign brands and avoid all Chinese-branded infant formula. Finally, while we knew the company had to execute well, we underestimated the growing pains it would have in managing its production, inventory and distribution.

Describe how you approach valuation.

DK: As shorthand, we look at the current free-cash-flow yields of a company based on our estimates for this year and next year. We then calculate what we believe those yields should be based on the quality and growth of the future cash flows. Our expected yields will also depend on the risk-free rate, using the 10-year Treasury as a proxy. We want to buy businesses at at least 30% discounts to our expected free-cash-flow yields. This gives us a margin of safety in case our investment thesis doesn’t play out according to plan.

You target having a concentrated portfolio of eight to twelve positions. Describe your rationale for that.

DK: We want to build a portfolio of our very best ideas. By the time we get out to our 15th-best idea, we’re not really happy with the risk/reward proposition. In our minds, a portfolio with a limited number of carefully-selected names is the only way to significantly outperform benchmarks over the long term.

The fear, of course, in running a concentrated portfolio is that a large underperforming position can hurt overall performance. Over the past 12 years we’ve had 43 positions with gains or losses above $10,000. Of those, only six were losers, and three of those were very close to breakeven. The biggest loss, American Dairy, resulted in less than a 5% hit to the fund’s performance. Avoiding big losers has certainly helped our performance since inception.

To touch briefly on risk management, we don’t employ any of the complicated and usually ineffective financial engineering you often see used by our hedge-fund peers. We think the best way to mitigate risk is to own high-quality companies with durable competitive advantages, superior business models and clean balance sheets, and to add them to the portfolio only when we have that wide margin of safety. People are surprised to learn that with such a concentrated portfolio we were down only about half of what the S&P 500 was in 2008. We attribute that to the types of companies we own. Companies that generate predictable and growing free cash flow usually have a natural floor to their share prices.

With a long time horizon and such a concentrated portfolio, do you trade much?

DV: Once we build a position, if there are large dips that we believe are unjustified we generally look to buy more. This happens with some regularity, as in September when there was a sharp rotation from high-quality businesses to lower-quality cyclicals, banks and energy stocks. We added to some of our positions at that time, but we hadn’t bought or sold anything prior to that since April.

I would mention that when it comes to selling, we exit a position in its entirety when it reaches our estimate of intrinsic value. We don’t understand the reasoning behind selling some and holding some – we buy it when it’s attractive and sell out completely once it reaches full value. Or, as in the cases I described earlier, if we have better ideas that we want to take advantage of.

Do you often hold cash?

DK: Since 2007 we have averaged around 19% cash, not because we’re market timers but because we only put cash to work when great ideas present themselves. Our cash level today is under 5%, which reflects our enthusiasm for the return potential of our current portfolio.

Flesh out in more detail the bright prospects you see for Moody’s.

DK: Moody’s and S&P rate more than 90% of all bonds receiving credit ratings worldwide. The natural duopoly exists because if a large debt issuer, let’s say IBM, wants to issue $5 billion of debt, it’s not worth their time to deal with smaller ratings competitors who may be offering cut-rate pricing. Not having a rating from S&P or Moody’s brands the offering as inferior, requiring the issuer, all else being equal, to pay a higher interest rate of 30-50 basis points on the debt. That added expense dwarfs any potential savings on the ratings fee.

There are a number of positive trends in favor of debt issuance. With interest rates low, it’s an attractive time to raise debt. Entities in emerging economies like China and India are increasingly looking to access worldwide debt markets, and they see the ratings agencies as important partners for gaining such access. You also see trends like bank disintermediation in Europe, where commercial lenders have reduced lending to retain more capital on their balance sheets. As they pull back, more European companies are going directly to the marketplace for debt financing. The anticipated debt that will need to be issued and refinanced over the next five years is a staggering number.

In part to leverage data generated from the ratings business, Moody's has been building out its analytics business in recent years, including a large European acquisition of a company called Bureau van Dijk in 2017. Is that effort important to your thesis?

DK: I would have to say no. We like areas where the analytics business can easily leverage ratings data to generate incremental revenue and profits. But we’re not supportive of acquiring unrelated businesses to bolster the analytics franchise. We see the ratings business, which accounts for roughly three-quarters of operating profits today, as the main driver of intrinsic value growth going forward. Bureau van Dijk was an expensive acquisition that was intended to offset the more volatile earnings of the ratings business, which I couldn’t care less about. Management would have created far more intrinsic value by using the purchase amount to instead buy back their own stock.

How high do you consider the regulatory risk around the company today?

DK: Moody’s is a relatively easy punching bag for politicians and it clearly made some faulty assumptions with respect to mortgage debt during the financial crisis. But its ratings overall have generally been quite good predictors of default risk, and we’d argue that additional regulations put in place by the Dodd-Frank reforms after the financial crisis have actually solidified the ratings duopoly. Meeting the added regulatory standards is quite expensive and time consuming, making it more difficult for smaller players to compete.

There is also always the threat of litigation by purchasers of debt who claim that reliance on the company’s ratings led to a loss. But since the financial crisis Moody’s has more clearly separated itself from the debt-underwriting process and is no longer formally part of offering prospectuses. We believe that approach provides protection on the litigation front.

The shares at a recent $218 are within 2% of their all-time high. How are you looking at potential upside from here?

DK: On our 2021 estimates of free cash flow, the stock trades at a free-cash-flow yield in the low-4% range on today’s enterprise value. Against a risk-free rate of 1.7% – which we think is more likely to go down than up – that to us is a highly compelling yield. This is especially true given our view that the company can grow EPS and free cash flow at least at a low-teens rate for the foreseeable future. We have owned Moody’s for over ten years and can see ourselves owning it for at least another decade.

What’s behind your continued enthusiasm for Fair Isaac?

DK: We want to invest in companies that sit at the top of their industry food chains, and Fair Isaac occupies that spot within the consumer-credit ecosystem. The company has long been a steady generator of free cash flow and a great capital allocator – it retired over 40% of its outstanding shares in the ten years prior to our purchase – but the problem was that it wasn’t really a strong organic grower. This changed with its recent shift in pricing strategy and we think the runway for pricing power is extremely long.

Why?

DK: Any consumer-credit decision made by a lender generally requires a credit score, and the cost of the FICO input into that decision is miniscule relative to the overall expense. On a $400,000 mortgage, the FICO score may cost the lender less than $1. We don’t think it’s unreasonable to assume FICO could charge a multiple of that without impacting demand.

The company in 2018 raised prices more than 30% on its mortgage scores, and earlier this year they instituted a similar special increase for auto-loan scores. They plan to continue rolling out these increases from one category to the next, and we believe they will also be able to institute regular annual price increases at above inflation for years to come.

Can anything else drive potential growth?

DK: Not unlike Moody’s with its analytics business, FICO has invested in building a software business that seeks to leverage the data generated from the scores group. The return on investment for this effort is not yet clear, but in the latest quarter this business accounted for roughly 30% of the company’s overall operating profit before unallocated corporate expenses. As in the case of Moody’s with analytics, the software business here is not critical to our long-term investment thesis.

On the scores side, the company is starting to look more outside the U.S. Consumer credit scores are not nearly as widely used today for credit decisions in foreign markets, but the company is partnering with banks in places like Brazil, China and India to create footholds that we think can ultimately translate into significant opportunity around the world.

The stock at around $302 is off its highs of last September but is still up more than 60% year to date. How are you looking at valuation from here?

DK: The stock is not that well followed by analysts, and we don’t think the current valuation properly reflects the future power of the business model. Today’s free cash flow yield on our 2021 estimates is around 3.5%, which makes it more expensive than Moody’s but is still twice the yield of the 10-year U.S. Treasury. On top of that we believe the potential for EPS and free cash flow growth is greater than it is for Moody’s; this could be a mid-teens compounder for many years.

If you looked back on this in a couple years and turned out to be wrong, why do you think that would be?

DK: Based on what we know, we believe the software business is at an inflection point and can become a lot more profitable. If we were to be wrong on valuation, it would most likely be because that business came in below expectations. That said, we think we’re being conservative enough in modeling the scores business that it could more than offset any weakness in software.

Visa [V] shares for years have seemed expensive and the story behind them known, but the stock price keeps compounding at a high rate. How does that happen?

DK: I’d actually argue that Visa’s large market cap and the familiarity people have with the name generally makes it an uninteresting choice for the typical value investor. But the fact remains that there are few businesses of this size with a comparable market position and as-attractive secular growth drivers. That story hasn’t really changed, and we expect it to continue for many years to come.

Taking a step back, Visa and Mastercard [MA] facilitate the vast majority of non-cash payment transactions in the world. They take a very small piece of each debit and credit card transaction, and such transactions continue to account for an increasingly greater share of payments worldwide. The two companies generally compete rationally and consistently exercise their pricing power.

There have been and will likely continue to be concerns about new technologies and/or competitors disrupting the companies’ powerful business models. But I would argue Visa and Mastercard have actually solidified their roles in the ecosystem, and we’re much less worried about disruption today than we were three or four years ago. PayPal was going to circumvent their networks but now happily works in concert with them. Stripe now takes Visa and Mastercard. We also don’t view cryptocurrencies as a credible threat.

Another concern is that very large merchants like Amazon, Walmart or Costco could try to take advantage of their scale and eliminate Visa from their payments ecosystems. That hasn’t happened yet and I tend to think it’s not worth it for even the biggest merchants to risk losing customers over how people want to pay. In general, Visa and Mastercard have their hands in every type of payment system that works around the world and when people have tried to circumvent them it has not been fruitful.

Are there important global gaps in the secular growth story?

DK: The biggest issue has been China, which has favored local payment providers, in part due to sensitivity around who controls and has access to credit-card data. We don’t know when China will fully open its payments marketplace, but there are clear advantages for it to embrace electronic payments and work with Visa and Mastercard in that process. Our investment thesis assumes very little contribution from China and any significant uptake there would be additional upside to our valuation.

How attractive do you consider Visa shares at today’s $179 price?

DK: The free-cash-flow yield on our 2021 numbers is about 4%, for a company that we believe can consistently increase free cash flow per share in the mid-teens over the next decade. To my point earlier about this being a mundane choice, we view Visa as an exciting technology company but don’t think it’s being valued as such.

Another important element here is capital allocation. Given its level of free cash flow and its relatively low reinvestment needs, the company has regularly retired 2% to 3% of its stock on an annual basis. That adds up over time and is a real positive for a long-term investor.

Do you see material differences in the outlooks for Visa and Mastercard?

DK: There are slightly different stories to tell. Visa has been more U.S.-centric but bought Visa Europe in 2015 and continues to remove costs and integrate that business. Mastercard has been somewhat more entrepreneurial in making acquisitions to expand into different parts of the payments food chain. Mastercard has consistently generated lower margins and is working hard to narrow that gap. All in all, we think both companies are worth owning at today’s prices.

Describe why Intuit [INTU] fits your profile of an attractive investment.

DK: Intuit doesn’t get the same type of publicity many of its software peers do, but it has been an excellent company for a long time. It has two market-leading franchises, QuickBooks accounting software for small- and medium-sized businesses and TurboTax tax software for those same businesses and for individuals.

The driving mission behind the company’s products is to make the financial lives of business owners and consumers easier. Small businesses can keep their books on Excel spreadsheets and handle things like payroll and tax preparation separately, but QuickBooks helps them streamline all that in a way that saves time and money. The product’s ease of use continues to improve, which not only helps keep retention rates of existing customers high, but it also continues to grow the overall pie by attracting new users. The same is true with TurboTax, which has become so user friendly that people continue to come to it rather than do their taxes by hand, while also offering a less-expensive alternative to hiring a tax advisor. Once users get on these platforms, the transfer of information from year to year makes both products inherently sticky.

Is this one of your ten-plus year holdings?

DK: We built the majority of our current position a few years ago when it began transitioning its business model from selling pieces of software that you buy once every four or five years to selling annual subscriptions. That greatly increased the efficiency of how the products were delivered and, with lower upfront costs, improved pricing power as well.

While the business-model change was attractive, we would not have invested if we didn’t believe the company was also becoming more disciplined in its capital allocation. It had made a number of acquisitions meant to add bells and whistles to the core products, but they turned out to be mostly busts. Management appeared to have learned from those mistakes and began refocusing on the company’s core strengths, which made it investable for us.

After 11 years as CEO, Brad Smith retired early this year and was replaced by long-time company veteran Sasan Goodarzi. Has that transition gone smoothly?

DK: Whenever management changes we worry primarily about whether there’s going to be a fundamental shift in capital allocation. Is the new CEO an empire builder who is going to make a lot of acquisitions? Is he or she committed to returning capital to shareholders? We generally think the transition has gone smoothly, but we do wish the company were steadier in its repurchases of shares. We don’t think management should try to time the market quite as much as it does in buying back stock.

There’s been some controversy on the TurboTax side with respect to free-filing offers for customers. Is that a big issue?

DK: The IRS requires that for the very simplest returns people be allowed to file electronically for free. Intuit is willing to serve that customer in order to get them into the ecosystem and then potentially build the relationship over time, but there were some complaints that the company wasn’t making the free option as clear as it should have. We don’t agree that was necessarily the case, but the issue hasn’t been a difficult one to resolve and it doesn’t affect our view of the long-term health of the business.

The shares at a recent $260 don’t appear particularly cheap. How are you looking at the potential from here?

DK: Investors are very focused on steady, predictable earnings, and Intuit very much fits that bill. But it actually doesn’t trade as richly as some of the more traditional consumer-products stocks. On our 2021 estimates, it trades at a 4.2% free-cash-flow yield. We think that’s quite attractive given that we believe free cash flow can grow steadily at a mid-teens rate. Growth like that can make a stock less expensive relatively quickly.

Do any particular macro views inform what you own or how you’re managing your portfolio today?

DK: I mentioned earlier that we generally want to own companies for which the macroeconomic outlook is not a primary driver of performance one way or another. However, one thing we do have an opinion on today and that we consider a critical determinant of equity-price levels going forward is interest rates. We think a legitimate case can be made – having to do with demographics, political imperatives and employment trends impacted by automation and artificial intelligence – that while interest rates are in a low range today, they very well may stay in this range for a long time or even go lower.

ON VALUATION:

If we have the prolonged period of low interest rates that we expect, equity multiples from today should expand.

If we have the prolonged period of low interest rates that we expect, people are going to be willing to pay higher prices for equities and equity multiples should expand. This will, in our view, be particularly true for companies that have predictable and growing earnings, which makes us even more excited about our current portfolio company valuations.

You’ve done a number of different things already in a varied and successful career. Do you see any other career changes in the offing?

DK: Investing in stocks has been a passion of mine since I was eight years old, and it still gets me excited every day. So, I expect Valley Forge Capital Management to be the final chapter of my investment career and hope to be running the firm for at least another 25 years.