Robert Bob Robotti Builders FirstSource BLDR Atwood Oceanics ATW Westlake WLK Panhandle PHX BMC BMCH Subsea SUBCY Tidewater TDW Norbord OSB LSB LXU Schlumberger SLB Homebuilding

At the risk of over-generalizing, your investments would seem to be more bets on industry cycles improving than individual companies improving. Is that fair?

Robert Robotti: When I started my business in the early 1980s my original focus because I’m an accountant was on buying cheap stocks relative to companies’ balance sheets. So I bought a lot of cheap stocks and found out in many cases why they were so cheap: they were poor businesses that couldn’t justify their book value because they weren’t going to generate adequate returns on it. That generally made them poor investments.

What I found did work was investing in companies that were discounted but run by very smart capital allocators who knew how to grow the business, or that were in understandable, cyclical businesses that were cyclically depressed. That’s where we’ve ended up spending most of our time.

It’s not that we won’t invest in companies with their own idiosyncratic issues. We’ve spoken with you before about Skechers [VII, May 27, 2011], the shoe company that had a very hot product flame out and left it struggling with bloated inventory and litigation over intellectual property. In that case we thought the stock was discounted enough that even an unambitious recovery of earnings power could provide a lot of upside in the stock. If to justify the purchase we’d had to get too deep into making calls on the fashions and trends in shoe retailing and Skechers’ ability to come up with the next hot product, we probably wouldn’t have done it.

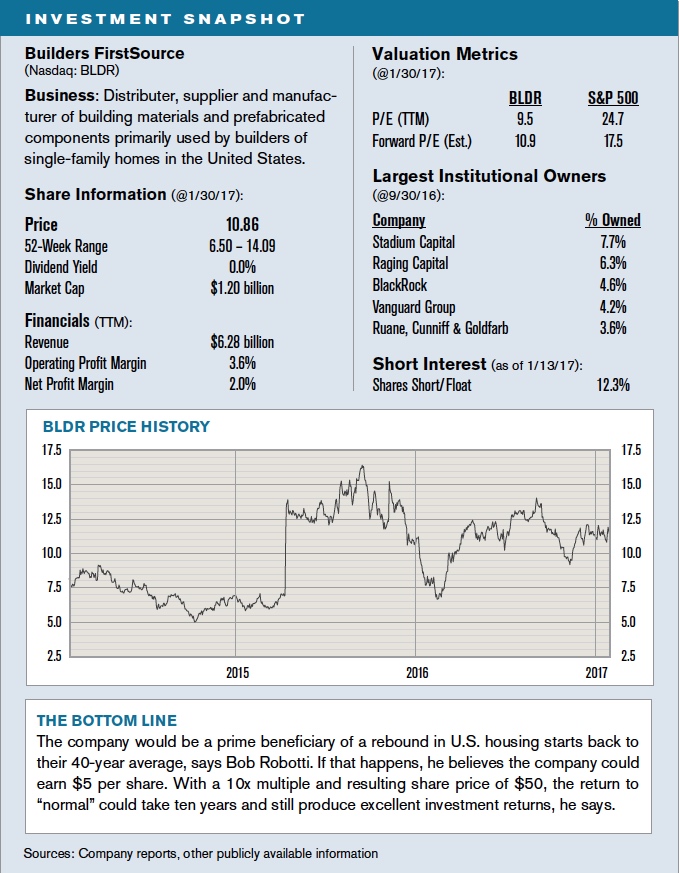

Contrast that with looking at homebuilding in 2009. Single-family housing starts in the U.S. were at around 450,000, an all-time low over a period in which the population had significantly increased. As an investor, it’s an easier starting point for me to conclude that this level of housing starts was not the new norm and then go out and look to invest in companies like Builders FirstSource [BLDR] or what is now BMC Stock Holdings [BMCH] that we thought were well positioned to benefit from a homebuilding recovery. I have more confidence in my ability to do that well than to figure out if Skechers’ product pipeline is up to the task.

ON TAKING RISKS:

I will invest in firms where the possibility the equity goes to zero has to be recognized as part of the equation.

One important skill when investing in deeply cyclical stocks is to avoid the ones that don’t make it through the cycle. Any advice on that front?

RR: I’d make a couple points on that. One is that we try to emphasize companies with some level of differentiation that allows them to grow through the cycle and substantially improve their competitive positions in the downturns.

We’ve also spoken [VII, March 31, 2015] about Subsea 7 [SUBCY], the largest global service provider in the engineering, design and implementation of complicated deepwater drilling projects. We believe its expertise provides it with a differentiated and sustainable advantage in an area of the market, deepwater, that continues to grow as a percentage of energy-majors’ total exploration and production budgets. The company’s scale and balance sheet allow it to opportunistically invest through low points in the cycle when others struggle. The result is that it’s a growth business with cyclical earnings, which allows us to buy in cheaply at various points in the cycle without the same level of risk we’d have in a less-differentiated commoditized business.

The second point I’d make is that in certain situations I will invest in companies where the possibility the equity goes to zero has to be recognized as part of the equation – and my record on that front is not spotless. Charlie Munger has talked about how depending on the probabilities you assign to the up and down case, it may be a perfectly reasonable bet to accept the possibility of a zero if your upside is 5x or more. I agree.

When I first invested in it in 2009, Builders FirstSource was troubled, losing $50 million a year. I thought the business and the balance sheet were strong enough that it would make it through the worst of the cycle, but there was some chance of a zero. But as is the case with many of our ideas, our base-case upside was many multiples of what we were paying. If things got really bad we expected a capital raise that would dilute our stake, but the margin of safety was big enough that even if that happened we thought we’d come out fine. That’s exactly what happened – shares outstanding have more than doubled – but our returns so far have been very good and we still believe there’s a considerable amount of upside from here.

A more recent example?

RR: We own a significant stake in Tidewater [TDW], which operates a fleet of marine service vessels for offshore energy projects. With the potential for a zero as part of the equation, why did we invest? It’s the asymmetrical nature of the investment. Based on normalized earnings power – even assuming sizable equity-dilution risk – we think the shares can trade at 4-5x where they are now, maybe more. If we can buy something like that at 4% of book value, with assets that are relatively new and competitive in their markets, that’s a risk/reward we’re willing to take with a limited portion of our capital.

Given what you’re looking for, how do you tend to generate ideas?

RR: We often find new ideas in industries in which we’re already active. Our stake in Builders FirstSource led us to invest in BMC, where we owned 15% of the equity and I was on the board from 2012 to 2015. From owning both of those companies we learned a lot about all kinds of homebuilding products, one of which that caught our eye was oriented strand board [OSB], a substitute for plywood in framing out a house. The market for OSB had gotten way oversupplied, depressing supplier prices and margins, but we expected that to correct as demand from builders improved and new capacity was unlikely to come online. We then went looking for the prime beneficiaries of OSB pricing coming back and ended up investing in Norbord [OSB], whose stock was extremely cheap, which had a savvy 50% owner in Brookfield Asset Management, and which had significantly improved its market position in 2015 by merging with a large competitor.

As somewhat of an aside, I would argue that the stocks of many suppliers to homebuilders are interesting today even though their share prices have recovered dramatically from their lows. Single-family housing starts should increase sharply from current levels and many of the supply businesses – as is the case with oriented strand board – would not have to add any capacity. So contrary to the general perception, for at least the next few years a lot of these supply businesses should be less susceptible to negative cyclicality, given how low we are today in the cycle, and should be much less capital intensive, given the slack capacity available. Maybe that impacts how they’re valued, but even without a re-rating that means they have the potential to generate a considerable amount of free cash flow.

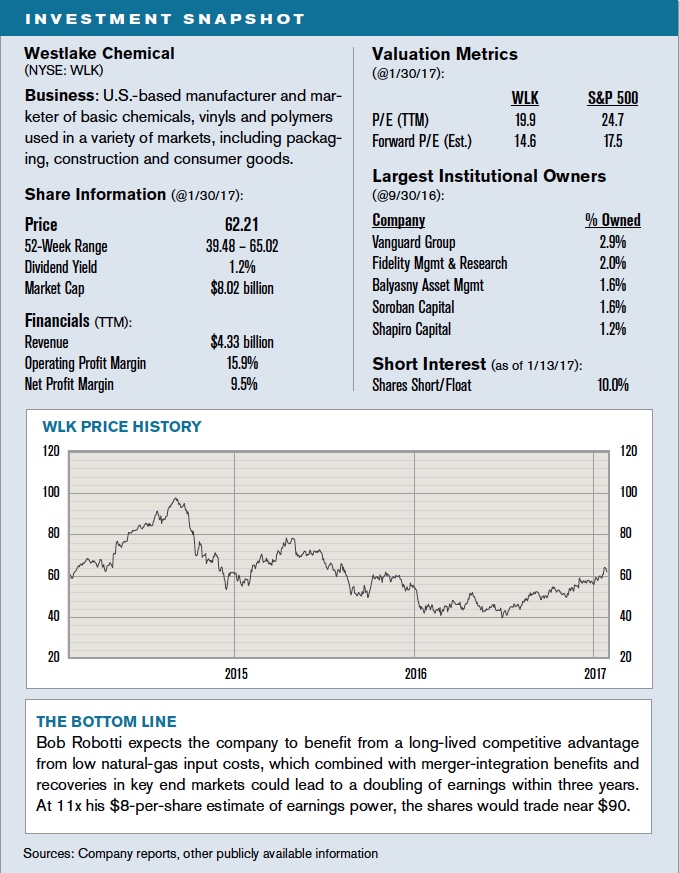

A related source of ideas for us is following industry-related themes. For example, given the vast amounts of low-cost developable natural gas in North America and the difficulty in exporting it, we believe natural gas prices here will remain low and disconnected from world energy prices for maybe the next ten years. Who are the beneficiaries of that? One we’ll talk about later is Westlake Chemical [WLK], which is 70% insider-owned, generates considerable free cash flow that it reinvests intelligently, and has a competitive advantage against global players whose input costs are significantly higher.

ON TIME HORIZON:

We look out two to three years but require enough margin of safety that we’ll be fine if our timing is wrong.

LSB Industries [LXU] is another beneficiary of low natural-gas input costs, in this case for its main fertilizer business. The shares have been beaten down by where we are in the global agriculture cycle and by disastrous cost overruns at a large new ammonia plant that has finally been completed in Arkansas. This one has been a bit painful so far, but we still believe the thesis is intact and that with the capital spending done, an upturn in the agricultural cycle, and the ongoing benefit of low gas prices, the normal earnings power on the business can justify a share price that is a multiple of the $8.50 at which it trades today.

Do you have a cap-size sweet spot?

RR: I would say we’re cap-size agnostic, but we’re typically starting out in a company when it’s not that well-known or appreciated on Wall Street. Something like Schlumberger [SLB], the leading oil-services firm, has over the past 30 years shown that it’s a well-run company in a cyclical business that has been a good stock to own. We’re looking for companies like Schlumberger, but because they haven’t demonstrated how good they are for as long as Schlumberger has don’t yet get the same type of appreciation – and valuation – from investors. Of course we hope they all get there, and that we’re smart enough to hold on to them as that happens.

With what time horizon do you typically invest?

RR: When making a new investment we’re usually looking out two to three years, but we require enough of a margin of safety that we’ll be fine if we get the timing wrong – which we often do. When I invested in Builders FirstSource I thought U.S. single-family housing starts would get back to the 40-year average level of more than one million by 2014. I still believe that will happen, but it’s 2017 and it hasn’t happened yet.

We’ve owned many stocks for a very long time. SubSea 7, for example, I’ve owned in greater or lesser amounts for 20 years. The shares are up 50% from last March, but when we look at it today we see the potential, in U.S.-dollar terms, for the company within the next three years as activity levels come back to earn as much as $3 per share. That’s better than the 2014 peak of around $2.40 – since then they have reduced the cost structure of the business, finished a large cap-spending cycle, formed differentiating alliances, and seen some key competitors go away. They have access to plenty of capital for growth. If we’re right on earnings power and the stock earns even a 10x multiple, we’re at a $30 price. That can take longer than we expect and we would still have an attractive IRR from the current price. [Note: Subsea 7’s U.S. ADRs currently trade at $13.65.]

Time horizon is an edge we can have. We’re intensely focused on maintaining perspective as new information arrives, but frequently our additional analysis confirms the need to remain patient. Very often throughout our history our long-term conviction has led us to double up when a position initially works against us.

All this is difficult, especially when you’re managing other people’s money and inactivity can imply ignorance or indecision. We think a decision to remain patient is an active decision, no less important than buying or selling. Fortunately our client capital aligns well with this view. You can’t have a patient, long-term view with actively impatient client capital.

Is it fair to say your valuation efforts revolve primarily around estimated normal earnings power and applying a normal multiple?

RR: We are very much focused in our analysis and valuation on the earnings power of the business when the broader industry cycle or trends play out the way we expect. I wouldn’t say, though, that we count on a “normal” multiple. We want to be able to justify any investment using below what we might consider normal multiples. We do usually expect the multiple to go higher than that, but we don’t need that to find the opportunity attractive.

Do discounted-cash-flow models add value for the types of situations in which you’re investing?

RR: Very often not. In most DCF models you estimate cash flows a certain number of years out and then assume some terminal growth rates for revenues and costs. That’s not so relevant in highly-cyclical businesses. Changing around your assumptions on the timing of the cyclicality has a dramatic impact on the present values you calculate. It’s just not an approach we’ve found very helpful. In many cases it’s nothing more than what I call a “Deliberate Certainty Fabricating” model.

Describe in fuller detail your investment case for Builders FirstSource.

RR: As I’ve mentioned, our view is that the current depressed level of single-family housing starts in the U.S. doesn’t come close to reflecting the normalized level of homes that are going to get built. After bottoming in 2009 at an annual rate of 450,000, single-family starts today are around 800,000, but we believe the normalized number is at least 1.1 million, which is the 40-year average. That assumption is likely conservative given how much higher the U.S. population is today relative to the average over those 40 years and given the increasing need and demand to replace a large number of homes built in the 1950s and 1960s. We believe there’s a long runway of growth ahead.

Builders FirstSource is a national distributor of home-construction materials including lumber, oriented strand board, doors, windows and siding. It also manufactures and distributes value-add products such as roof trusses, floor trusses, wall panels and its own windows, doors and moldings. These prefabricated products, which account for more than one-third of revenues, have higher margins for the company and help builders reduce waste, labor costs and cycle times.

In investing here, I don’t need to analyze all the individual markets and make judgements on what’s going on in Salt Lake City or Dallas. Builders is in almost every important U.S. market and is well positioned to benefit as homebuilding overall recovers. Its scale provides it with cost and product advantages, which will likely only increase as the still-fragmented industry continues to consolidate.

The company took on quite a bit of leverage to acquire competitor ProBuild in 2015. Is that a concern if the recovery in building you’re counting on stalls out?

RR: We thought the acquisition was strategically smart, forming the only company in the industry with a real national presence. As for the risks of a downturn, proforma trailing-12-month EBITDA is $373 million, versus net debt of $2 billion. The bulk of the debt is due in 2022 or later, with the only earlier maturity a $150 million credit facility due in 2020. We generally think the nature of the debt is benign – all they need to do is make the interest payments, which we consider quite manageable even in a slowdown. I’d also add that any slowdown from today’s low volume levels would be modest relative to past down cycles.

How are you looking at upside from today’s share price of around $10.90?

RR: The company’s financials are highly sensitive to housing-start activity levels. With the first 50% increase in housing starts off the bottom in 2009, prices also rose 30% and industry revenues doubled. If we got to 1.1 to 1.2 million starts a year from today’s levels we’d expect revenues to double again on similar price and volume increases.

Management says EBITDA margins on incremental sales are around 15%, so we assume margins get to 10% on a doubling of revenues. That would result in $1.2 billion of EBITDA, which translates into $5 per share of earnings if we assume debt is reduced to $1 billion using free cash flow. Put a reasonable 10x multiple on that and the shares would trade at $50.

Even if it took ten years to get there, that’s a 15% annualized return from the current price. We don’t expect it to take that long, but that’s a nice margin of safety in case things don’t happen exactly as we expect them to.

Before turning to a couple energy-related ideas, can you give a general overview on how you’re thinking about oil prices?

RR: As we’ve all read, OPEC and certain non-OPEC oil-producing countries have tentatively agreed to scale back production. Markets in the commodity and in the shares of companies perceived to benefit reacted favorably right away. While that development consumes the headlines, only time will tell if these production cuts actually happen.

My view is that this news of cuts is more the “tail” rather than the “dog.” The dog is the demand for oil over the next few years versus its supply. Here we believe demand will continue its slow growth while supply from existing, completed wellbores continues its inexorable decline. That supply is not being replaced as capital investment in drilling and completing new wells continues at a fraction of where it was for many years. That pushes us closer to tight global supply. If certain producers actually cut back current production, prices will continue to increase. Over time we believe the incremental production necessary to keep oil-market supply and demand in balance requires a $70 to $80 per-barrel price.

Why do you consider the current cycle favorable for Atwood Oceanics [ATW]?

RR: Atwood has been around for 50 years and currently owns ten offshore drilling rigs, split evenly between jackups and deepwater rigs. This is a classic cyclical business which found itself with way too much capacity as oil prices declined. The current environment is triggering a reduction in supply, primarily from the attrition of a substantial number of outdated rigs. We think the supply side is now about halfway through its correction.

Because the average age of its fleet is relatively low Atwood has not had to scrap any rigs, and after taking delivery of two new rigs in the next three years it will have one of the more modern fleets in the industry. The flip side of having a modern fleet, of course, is that it must somehow be financed. Atwood successfully pushed out a sizable debt maturity to 2019, but it’s important to the company that at least some pricing power returns to the market before then.

We think that will happen because we don’t believe in the consensus view that onshore shale produces the incremental barrel that will replace offshore production. Offshore drilling has gotten much cheaper – Atwood’s deepwater day rates have declined from $600,000 to below $200,000 in the last two years – and at those rates there are many offshore developments with $40-per-barrel or lower breakeven costs. As that triggers a restart of demand, day rates should begin to recover. With a fleet that before long will require minimal capital, Atwood’s free cash flow should allow it to pay down debt to the benefit of the equity.

Has rig demand picked up yet?

RR: There hasn’t been any pickup to date. Most E&P companies still aren’t spending on new projects due to tight capital and/or the prioritization of dividend payments. But that can’t go on forever. If they continue to defer new well investments they’ll be faced with material production declines in three or four years.

There are some signs in the last few months of a resurrection of offshore activity. BP just committed to spend $1 billion on a field in West Africa. France’s Total announced a similar investment in Kenya. We think the industry will continue to commit new capital as long as oil prices remain relatively stable, even without a much higher price. As continued commitments eventually tighten the rig market, pricing power will shift back to companies like Atwood.

ON OFFSHORE DRILLING:

Deepwater offshore drilling is a favorite hedge-fund short. We think the obituary for it is extremely premature.

At today’s $12.20, how inexpensive do you consider Atwood’s shares?

RR: The company’s earnings peaked at $6 per share in the last cycle. The fleet is now newer and will be 20% larger with the two new builds coming in 2019 and 2020. Offsetting that increase in potential earnings power is that Atwood recently issued equity to help fund the construction of the new rigs. With all that, assuming day rates recover to around $500,000 per day – below the last peak – we estimate earnings power within the next few years of $5 per share. At what would be a reasonable 10x multiple that would translate into a $50 share price.

Given the 35% short interest in the stock, many investors would appear to disagree.

RR: Hedge funds are all over energy. They are long the best onshore shale companies so they need to short something to hedge their energy exposure and deepwater offshore drilling is their favorite target. As I mentioned, we think the obituary for offshore drilling is extremely premature.

There may be some groupthink at play here as well. Atwood’s stock trades at 33% of book value, while the subordinated debt is considered good money, trading at something like 92 cents on the dollar. I’d argue that both of those securities are mispriced.

The stock of Panhandle Oil & Gas [PHX], on whose board you sit, has weathered the energy cycle better than most. Why do you consider it attractive?

RR: Panhandle’s risk profile is different than that of traditional E&P companies. It has perpetual ownership of all the subsurface minerals on 250,000 net acres in the U.S., across a number of oil-and-gas basins including the Woodford, Fayetteville and much of western Oklahoma. Rather than funding geological surveys or land leases or drilling, Panhandle leases its land to E&P companies for an upfront payment plus a percentage of production. If it chooses, it also participates with partners in well development on its mineral holdings. It’s a low-risk, capital-efficient model for participating in oil and gas production and its returns on capital are much higher than those of the actual producers. This model is relatively unique in the public markets – mineral ownership like this is very fragmented and has tended to be passed down through generations.

How would you characterize the quality of the company’s acreage?

RR: Some of it is the best-located land you could hope for and some of it is goat pasture that through serendipity could turn out to be very valuable in ten or twenty years. I mention that because some of the company’s most valuable land was acquired long ago from a seller who wasn’t willing to segment his land, throwing in property in Arkansas that the company then didn’t want. It turns out that land is now in the middle of the Fayetteville shale, one of the more prolific natural-gas plays.

If the model is resilient, why do Panhandle’s latest reported earnings look so bad?

RR: Unlike the few other mineral holding companies that are public, Panhandle pays a modest dividend and reinvests the bulk of its cash flows to participate in development alongside successful exploration and production partners. Lower commodity prices do negatively impact short-term profitability and can result in some significant non-cash asset-impairment charges when prices implode. Unlike many E&P companies, however, Panhandle has continued to generate positive free cash flow through the downturn.

What do you consider fair value for the shares, recently trading at around $21.50?

RR: Relative to 2014 when Panhandle’s shares got into the low-$30s, more of its acreage is productive today, implying to us that as natural gas prices stabilize – which we believe is happening – there’s no reason the stock couldn’t get back into the low-$30s. There are also many free call options in the company’s portfolio. Because they are currently uneconomic, a material amount of the minerals owned are characterized as “resource” rather than “reserves.” As extraction technology evolves and new discoveries are made, over time some of that resource will be converted to reserves and then to cash flow. That doesn’t show up on the balance sheet and it’s difficult to quantify, but we think there’s potentially a tremendous amount of value there.

From oil and gas to chemicals, explain your bull case for Westlake Chemical.

RR: Westlake produces chemicals used in a variety of consumer and industrial markets, including packaging, automotive and construction. The basic building block for its production is ethylene, which can either be produced from oil feedstocks, such as naphtha, or from natural-gas feedstocks, such as ethane. On a global basis more than 50% of industry ethylene capacity is naphtha-based, but domestic producers like Westlake because of the cost differential between oil and gas in the U.S. will continue to use primarily ethane. That’s a big competitive advantage. Even at current oil prices the cost of using ethane is a fraction of the cost of using naphtha. If oil prices increase as we expect and natural gas prices stabilize, that differential will increase – and persist at increased levels for many years – and Westlake’s margins will significantly improve.

That alone wouldn’t have us this excited about Westlake. Another key part of our thesis is the confidence we have in the Chao family, which manages the company and owns 70% of the shares. They have a long history of smart capital deployment, which recently has been mostly directed back into the business – including the acquisition last year of a large competitor, Axiall, for $3.8 billion. Axiall was capital constrained and poorly run, with margins half those of Westlake, so we believe management has significant opportunity to cut costs and otherwise improve margins on the acquired business. In addition, the merger increases Westlake’s exposure to construction-related businesses, such as PVC building products, that are in the earlier stages of what we see as a significant recovery.

What upside do you see in the shares from today’s price of just over $62?

RR: We think the earnings power of the business is quite a bit higher than current levels. As the acquisition is integrated, oil prices rise and residential construction normalizes, we think earnings power over the next three years can come in closer to $8 per share, more than double the current level. At what we’d consider a reasonable 11x multiple, that would translate into a share price pushing $90.

You mentioned holding positions for a long time. What’s a recent example where you changed your mind and just got out?

RR: Two years ago we took a position in GameStop [GME], the videogame retailer, at a very low multiple of free cash flow. The questions about the business were well known, primarily around how fast online distribution of games would hurt them. Given the discount we thought we were paying, we thought it was an interesting opportunity if the ice took longer to melt than expected. As things went on the company made some acquisitions we weren’t so keen on and the movement online kept growing, with the result that we were losing conviction rather than gaining it. In this case we thought patience was a mistake, so we ended up selling maybe a year later.

When we spoke more than five years ago [VII, August 31, 2011] you talked about stepping up your efforts to invest outside the U.S., particularly in emerging markets in Asia. How’s that going?

RR: Especially when I speak quickly you’ll hear my Queens accent come out, so I’m at heart a very local guy. That made me kind of skeptical about doing anything overseas, but now that we’ve been at it awhile I think it’s made me a better investor. There will be bumps along the way, but the world has flattened and will continue to flatten. So understanding how business is done in China and Thailand and Indonesia is increasingly part of the equation in assessing a business in North America. My understanding of world business and finance is stronger today and I believe that results in better investment decisions.

Like a lot of the things we’ve been talking about, I don’t know if we’re at the bottom of the cycle for emerging markets, but I would suggest we’re at a low point. Many markets are out of favor and very discounted, which of course to our way of thinking makes them interesting.

Does the start of the new administration in the U.S. enthuse or concern you at all as an investor?

RR: I worry that further crackdowns on immigration could exacerbate the risks that we have too few workers in certain sectors of the economy. Homebuilders, for example, are already facing labor shortages in some markets, which drives up labor costs and would have the effect of hindering the cyclical comeback. Especially if that happens across multiple industries, it would have a negative impact on the economy.

Given our view that energy-intensive businesses in the U.S. are competitively advantaged, I also worry about any restrictions on trade that might limit those businesses’ ability to capitalize on the advantage. I fear there’s not enough recognition that we don’t need higher trade barriers in many industries.