Value investors are naturally drawn more to the tried and true when it comes to potential investments. Future assessments about a business may be slightly less prone to error in companies with long track records and proven business models. The conviction in the margin of safety uncovered in such companies' stocks may credibly be slightly higher.

But even hard-core value investors can't help but be interested from time to time in at least learning about companies with new products, technology or business models that might portend multi-bagger investment potential. This has so far been the province of Clifford Sosin [VII, September 29, 2017], who since founding CAS Investment Partners in 2012 has exhibited a keen ability to zero in on ideas with multi-year compounding potential before the market has fully bought in. His fund's annualized net return since inception: 35.3%, vs. 14.5% for the S&P 500.

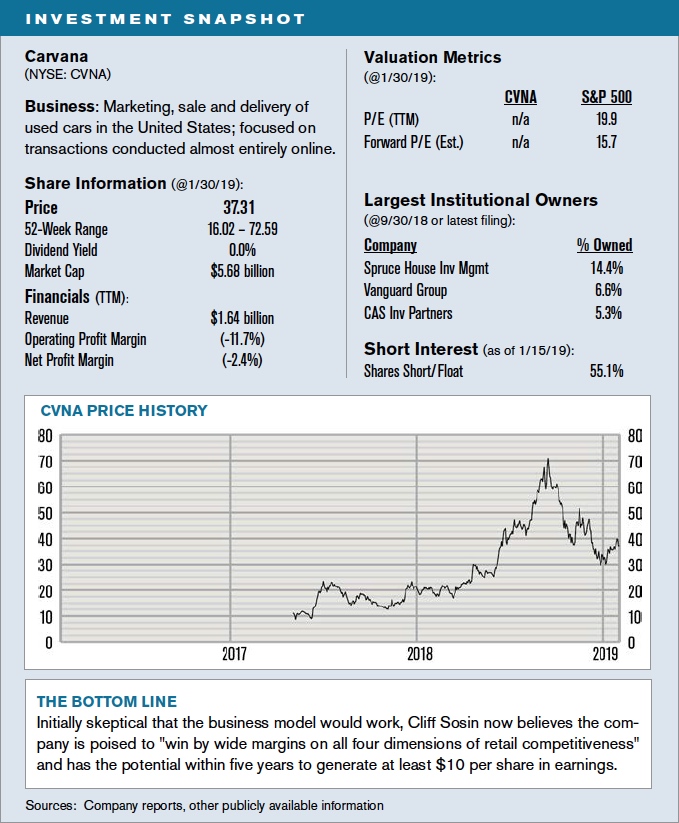

One of his more recent candidates for glory is online used-car retailer Carvana. The company sold its first car in Atlanta in 2013 and now offers more than 15,000 vehicles for sale with "as-soon-as-next-day" delivery in 86 markets across the U.S. Trailing-12-month revenues through September exceeded $1.6 billion, while profitability is still a work in progress. Having gone public in April 2017 at $15 per share, the company's stock went above $70 last September but has since retraced ground to trade recently at $37.30, giving it a current market value of $5.7 billion.

Sosin, who first bought Carvana shares early last year, was initially highly skeptical. He had spent considerable time studying the car-financing, car-retailing and logistics industries and came away thinking that selling cars online was a tough nut to crack. He expected it would be "kind of a disaster" when he first looked into Carvana's story, but instead found himself quickly intrigued. "Any time you come across something that differs significantly from your world view, you should always study it in more depth," he says.

Carvana's value proposition is relatively straightforward. Potential buyers research available vehicles in inventory online and, after making a selection, within as little as ten minutes can trade in their existing vehicle, finance the purchase of the new one and choose their preferred delivery date and time. The vehicle is delivered to the customer's home on a Carvana-branded hauler and, to compensate for the inability to test drive, the buyer then has a seven-day window during which he or she can return it for any reason and at no cost.

To deliver on this arguably superior buying process, Carvana maintains a network of large inspection and reconditioning centers [IRCs] to prep for-sale vehicles, which once sold are transported through a hub-and-spoke logistics network to the local-market "hub" it maintains nearest to the customer. From there it goes by single-car hauler to the buyer's home.

Sosin goes so far as to say that, "This is the only retail model I've seen that wins by wide margins on all four dimensions of retail competitiveness – price, selection, service and convenience." By eliminating dealer locations and associated personnel, even with higher logistics costs – which come down rapidly per unit as delivery-network density increases with the number of cars put through it – Carvana at scale should have lower operating costs per vehicle and be able to at least maintain the roughly $1,200-per-car price advantage it offers today, he says. Its 15,000-strong (and growing) inventory compares with the 50 to 150 vehicles on the typical dealer lot. Buyers interact with non-commissioned customer "advocates," there's no haggling over price, and returns are swift and efficient. As for convenience, if it all works, who wouldn't want to buy a car in ten minutes from your couch and have it delivered the next day? These advantages, he argues, should serve as high barriers to existing or new competition as well.

ON SELF-DRIVING CARS:

People think a shared fleet would be cheaper and better for most consumers. I don't think that claim is right.

The model will prove less attractive, of course, if fleets of autonomously driven vehicles cut sharply into used-car sales. Sosin isn't concerned. "People think a shared fleet would be cheaper and better for most consumers," he says. "I don't think that claim is right." He argues that after accounting for the miles introduced when autonomous vehicles drive empty and for the added costs of cleaning and maintaining shared cars, it's not clear that for the median driver a shared system would be less expensive. What would be obvious, he says, is that such a system would likely be an inferior experience for the average driver, who would now have to wait for cars to arrive, couldn't store anything in the car, and would lose the prestige value of a nice ride. "As America's primary means of travel, I'm betting car ownership will be around a lot longer," he says.

The central investment question on Carvana is whether the economics for it work over time. Sosin thinks the company within five years can be selling one million cars per year, or 2.5% of the roughly 40 million used cars sold annually in the U.S. On each car he estimates an average $3,500 in gross profit, less $1,500 in variable selling, general and administrative costs and in fixed overhead. Assuming an average selling price of $20,000, that would translate into $2 billion in annual pre-tax profit on $20 billion in revenue. Assuming a 25% tax rate, the company under his assumptions by 2024 would net $1.5 billion, or $10 in per-share earnings. While hardly a typical value investment, it's safe to say that if that reality comes close to true, the shares at today's $37 price will prove to be quite a bargain.