You started your career as an investor in Japan in the waning stages of a boom time, followed pretty much by 23 years of bear market ending in 2012. You probably would have been forgiven had you switched your market focus at some point.

Mark Pearson: Japan is obviously associated with many structural problems. The country’s population is aging and is on course to significantly decline. Plagued by chronic deflation, nominal GDP from 1997 to 2012 contracted by about 15%. The banking system almost collapsed several times, requiring government bailouts and semi-nationalization. Weak nominal GDP caused tax revenues to fall and the national debt to balloon.

My wife is Japanese and I committed to building my career here, but beyond that I also say that we are investors in the equities of companies, not in the country as a whole. It’s rather remarkable what many companies have done to adapt to a very difficult macroeconomic environment. We as investors have had to do the same thing.

We’ll talk more about companies, but before leaving the subject, would you call yourself optimistic about the macroeconomic situation today?

MP: We’ve seen a significant recovery in equities, but the expression “climbing a wall of worry” very much applies. Prime Minister Abe’s policies have been a catalyst for an economic recovery, although I’d argue it was probably coming anyway. But the negative structural issues largely remain. In my opinion, what Abenomics promised but hasn’t yet delivered is a more expansionary fiscal policy. When interest rates are at zero and you have deflation, you should not be concerned about the level of government debt. I believe the tight fiscal stance of the last 20-plus years needs to change for the country to turn the corner from deflation to inflation.

What makes me optimistic? The quality and health of the Japanese corporate sector is better than it’s ever been. The hubris and over-confidence that characterized the inflationary boom of the 1980s has been replaced by more realistic and prudent corporate stewardship. In the mid-1990s, the Japanese corporate sector had total net debt of about ¥350 trillion. That’s now gone and the collective net cash balance is at least ¥50 trillion. In the entire decade of the 1990s, total profits in the Japanese corporate sector were essentially zero. Now returns on equity and profit margins are approaching European levels, if not yet those of the U.S.

Another reason for optimism as an investor today is valuation levels that are exceedingly low. Once a decade it seems cheap stocks in Japan get very cheap and expensive stocks get very expensive, and that valuation spread today is as wide as I’ve ever seen it. With ultra-low interest rates it makes sense that the market prices long-term earnings growth higher than more volatile, cyclical earnings, but the extremes now – at a point when I don’t believe interest rates can go much lower – are remarkable. The market overall trades at 90% of book value and less than 11x estimated forward earnings. That’s certainly not expensive, but our Japan funds are trading at 45% to 65% of book value – which is mostly tangible book value – and from 5x to 7x forward earnings.

Think about that. Even if valuation spreads stay wide, a company you buy into at 5x earnings is adding 20% to its market value every year. Even if the multiple remains where it is – and history suggests it won’t stay that low – value is appreciating at 20% per year. That’s a compelling argument today for value stocks in Japan.

I’ll give you one quick example. Asanuma [Tokyo: 1852] is a mid-sized construction company that because of under-investment in public and private infrastructure saw its revenue base fall from ¥250 billion to ¥120 billion between 1998 and 2013. Since then market conditions have improved considerably, normalized margins are higher, the balance sheet has gone from net debt to net cash, and the company spends a much greater share of its earnings on dividends and buybacks.

Asanuma’s share price is ¥3,500, there’s roughly ¥1,500 per share in net cash on the balance sheet, and annual earnings per share is at a current run rate of over ¥500 per year. So for a company that’s not capital intensive, with strong free cash flow and that isn’t at all at peak earnings levels, you’re paying a 4x P/E net to cash. The yield on the dividend expected in fiscal 2021 is over 8%. They’re looking to buy back 6-7% of the shares outstanding this fiscal year. Should the stock re-rate? We think so. All that eventually should line up pretty well for us as investors.

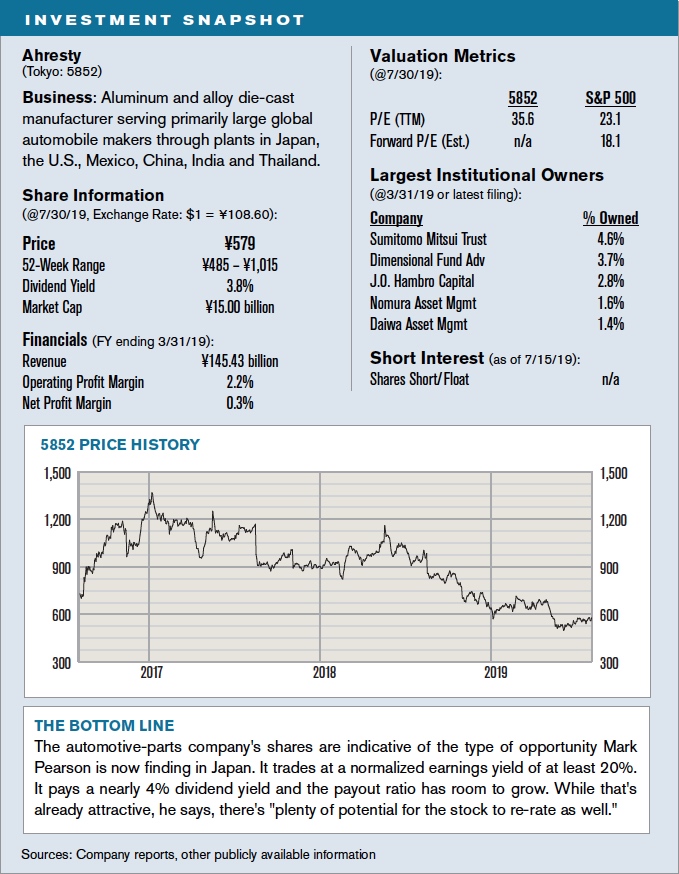

Auto-related stocks are optically cheap inside and outside of Japan. Describe the potential you see in one of your holdings in the sector, aluminum-parts manufacturer Ahresty [Tokyo: 5852].

MP: Parts companies like Ahresty have followed the big Japanese automobile manufacturers overseas as they’ve successfully established global footprints. There was always sort of a bargain struck, that if the parts makers came along they would be allowed to sell to others, and Ahresty has built a good business selling to companies such as General Motors and Volkswagen as well. It supplies customers from its production bases in Japan, China, Thailand, India, Mexico and the U.S.

Despite their higher cost, strong and lightweight aluminum parts have taken share because they support the ongoing quest by manufacturers for more fuel-efficiency. That and the company’s international expansion has driven steady sales growth over time – revenues were ¥63 billion in 1994 and are projected to hit ¥148 billion in the current fiscal year. Given that increasing fuel efficiency will remain critical regardless of the fuel source, we think Ahresty’s expertise in aluminum will be a long-term secular advantage.

That said, profits have been depressed in the past couple of years by factors that we believe should prove temporary. Model cycles can impact short-term results, and the way the cycles have hit in North America in particular have negatively impacted Ahresty's profitability. They’ve recently increased Mexican production capacity to supply North America, and that ramp up has had a negative effect on margins. In addition, a revamp of production processes for alloys in Japan has dampened efficiency as the new processes bed down. In the latest fiscal year operating margins – which have been as high at 6.4% but are usually in the 3-4% range – just barely made 2%.

How susceptible is the company to increasing trade conflict?

MP: Global Japanese companies are no strangers to trade pressures, and as a result have long located their production bases as close as possible to end markets. Restrictions on global trade would not be good for most global manufacturers, but Ahresty’s diversified production base should reduce the risk quite a bit. They did invest in Mexico based on expectations of the free-trade agreement between it and the U.S., so that remains a risk given the current political environment.

How susceptible is the company to competing alternatives to aluminum?

MP: It will always be important that they develop new and improved alloys required by customers, but for the most part, their products are used in a more structural capacity, involved with load bearing and heat. These don’t tend to be applications that are as suitable for potential alternatives like resins and plastics. Carbon fiber is also often not suitable as a replacement, as it’s much more expensive.

How inexpensive do you consider Ahresty's shares at today’s price of ¥580?

MP: If operating margins get back even to the low end of normal, or 3%, on run-rate revenues the company should produce over ¥3 billion in net income. The P/E on that at the current market capitalization of ¥15 billion is just 5x.

This is again indicative of the types of opportunities we’re finding. With no valuation re-rating, equity is compounding at 20% per year on market value. The dividend yield is around 4% and the payout ratio has room to grow. That’s already pretty attractive, and there’s plenty of potential for the stock to re-rate as well.

What’s behind your interest in credit-card company Credit Saison [Tokyo: 8253]?

MP: Credit Saison is a leading credit card issuer in Japan, #1 in terms of the number of cards issued and vying with Sumitomo Visa to be #1 by transaction value. This idea is similar to Ahresty in that we believe there’s a positive secular growth story that has been obscured by factors that have diminished in importance.

Credit-card usage in Japan still lags most other developed countries. In the U.S., for example, close to 60% of payment settlements are made using credit and debit cards, while the comparable number in Japan is less than 20%. The numbers are growing in both countries, but the gap is gradually narrowing, which is likely to continue as Japanese consumers slowly heal from the difficult economic environment over much of the past 30 years. The credit-card industry in Japan has been growing organically at more than 5% per year and we think is poised for solid growth for the foreseeable future.

The company’s profit has been constrained by a number of factors. Ultra-low interest rates have squeezed lending spreads and dampened revenues. An ill-advised foray into real estate development, which has since been written down and written off, resulted in unexpectedly large and drawn-out losses. Maybe most importantly, a significant update to the company’s information technology systems – which is now complete – was costly and took far too long. The biggest problem that caused was hindering the ability to engage new major partners on joint card-marketing programs. That pipeline is very important for companies like this and it’s been pretty dry for the past five years.

So our basic thesis is that the company is getting its act together and is well positioned to capitalize on the increasing penetration of credit and debit cards in Japan. People talk about new forms of payment emerging to disintermediate credit cards, but we think from a much lower base the traditional card business in Japan has significant room in increase share independent of whether new forms of payment do or don't take hold.

With the shares trading at a recent ¥1,320, how do you see all this translating into upside for shareholders?

MP: The stock trades at 7x consensus earnings estimates for the current fiscal year and 6x the ¥220 per share estimated for the fiscal year ending in March 2021. The current price to book value is 0.4x. This for a company in a secular growth market that we believe because of its position and its new capabilities can grow profits well ahead of the 5% or so organic growth in the market.

Again, there’s considerable prospective value accretion with a 17% earnings yield on fiscal 2021 numbers. There’s a 3.4% dividend yield. And there’s ultimately potential for multiple expansion, either because the market finally better understands the story or an acquirer tries to capitalize on the current depressed valuation.

Looking on the bright side of the market dynamics in Japan since you started investing, are you finding less competition out there for good ideas?

MP: We do definitely have fewer peers as the years have gone by. While you’ve seen some of this in other markets, there has also been quite a pronounced decline in the number of analysts and in the volume and quality of equity research in Japan. After 1989, for more than 20 years the securities companies went from being very profitable to struggling to survive as the market fell 80%. Very few deals were being done and it just wasn’t a market that supported deep analytical research coverage, especially reaching down to small and medium-size companies. In our small-cap fund 45% of our assets are in stocks that have no sell-side research coverage and another 25% have only one, two or three analysts covering them.

We haven’t asked about interest rates. Do they ever go up again in Japan?

MP: I don’t really make bets on this one way or the other, but we’ve seen a 35-year decline in interest rates and I have to believe we’re very close to if not at the end of that. Financial markets are broadly self-correcting over long periods of time – the seeds of the next cycle are sown in the extremes of the last cycle. The seeds of the current deflation were sown in the inflation of the 1970s and 1980s. The seeds of future inflation are very likely being sown in the deflation and ultra-loose monetary conditions of the current cycle. Trying to time that more precisely hasn’t been productive, though, so I try to avoid it.

All I can do as a humble value investor is try to appreciate companies that are survivors and perform essential functions, and take advantage when their stock prices seem as depressed as they are today.