Value Investor Digest readers can enjoy this recent interview with Artisan Partners' Dan O'Keefe from a recent issue of Value Investor Insight. You can access more great content by registering for a free trial. There is no obligation and no payment required. The trial subscription will include the current issue of VII, as well as our regular Bonus Content e-mails. To register, click here.

---------------------------------------

Don’t expect much equivocation when you ask Artisan Partners' Dan O’Keefe for his investment views. Investing in Japan is “terrible,” he says. The auto industry is a "miserable business and getting worse." And don’t get him started on Chinese corporate governance.

O’Keefe’s direct approach has translated nicely to investment success. The global-value strategy he's run since inception in 2007 now manages close to $18 billion and over that time the Artisan Global Value Fund has earned a net annualized 6.9%, vs. 3.9% for the MSCI All Country World Index.

Looking to be greedy, as Warren Buffett has put it, when others are fearful, O’Keefe is finding what he considers unappreciated value today in such areas as semiconductors, banks, online travel and defense.

Your defined strategy – “to invest in high-quality, undervalued companies with strong balance sheets and shareholder-oriented management teams” – sounds pretty familiar these days. Why do you consider that strategy as viable as ever?

Dan O’Keefe: We anchor our approach on buying businesses at discounts to their values based on the future cash flows they produce. If the stock trades at $75 and we think it’s worth $100, our primary source of return comes from that $75 approaching $100.

We’ve learned the hard way, however, that there are pitfalls to buying undervalued securities. You can often gravitate toward crummy businesses that rather than growing intrinsic value are shrinking intrinsic value. Price and value may converge, but at a lower rather than higher level. Another key risk of buying cheaply is that it can often mean buying a highly levered business. Cheap multiples in such businesses can turn expensive in a hurry.

That’s how we end up focusing on four characteristics: We start with undervaluation. We try to buy better-quality businesses so intrinsic value can grow and provide a second source of return. We try to stick to companies with balance sheets that reduce capital risk and improve operational and strategic flexibility. Then, of course, we also want to make sure that management is working in our interest as well as theirs. With those principles guiding our way, we believe we’re traveling down an economically attractive road without big potholes that can destroy value.

What’s a classic example of the type of company and situation that attracts your interest?

DO: One good example would be Marsh & McLennan [MMC], which we’ve owned in the global strategy since 2007. It’s the world’s leading insurance and reinsurance brokerage, one of only two companies in the industry – along with Aon [AON] – that has the fully global capabilities that the best of its customers require. The business isn’t balance-sheet intensive and benefits over time from the increasing value of assets that need to be insured. All that results in the company earning operating margins in the 20s and very good returns on capital.

Our original opportunity to buy was the result of a fairly unique situation. The company had come under attack by the state of New York for using a common-at-the-time commission structure in the industry that regulators thought created inappropriate conflicts of interest. In a panic to defend itself against greater regulatory scrutiny, the board named a new CEO who happened to know a lot about compliance but very little about selling insurance. So even as the regulatory issues were addressed or otherwise went away, the underlying brokerage business was terribly mismanaged, causing profitability and the stock’s valuation to fall off a cliff.

We knew and liked the insurance-brokerage industry and Marsh & McLennan’s position in it, and we were confident they would eventually have a CEO who could return the business to its potential. That’s what happened and the company has been extremely well run since.

Are you relying on comparable “fairly unique situations” to create discounted opportunities today?

DO: Let me say a few things about the environment that help explain the stock market we live in. First, it’s basically a low-growth world. All major economies are growing less than they have historically and probably less than what's needed to maintain social peace. We’re seeing that reflected in politics, here and abroad.

The second important thing is how central banks and monetary authorities have responded to this low-growth environment. The range of easy-money manipulation employed and the resulting generationally low interest rates are, in my opinion, toxic, distorting and counterproductive. They significantly disrupt the normal pricing mechanism of capital markets, which is made worse in equities by the flood of money into passive strategies. Passive money doesn’t have a pricing mechanism.

On top of all this, investors today are having to process nothing less than a new industrial revolution. Information technology writ large is destroying old industries as fast as it’s creating new ones.

Putting those three things together, investors today are desperately in search of what I call the “holy trinity”: will the business grow, will the business grow without being disrupted, and will it please provide me with some reliable income in the form of a dividend. That’s why the select number of companies meeting those criteria are extremely expensive, particularly in Europe. Heineken trades at 28x trailing earnings, Diageo at 26x, Hermes at 47x, L’Oreal at 36x, Beiersdorf at 32x. That is creating in some areas what appears to us to be a quality bubble.

We’re finding stocks to buy, usually in situations where companies have run into one-off types of headwinds. If those headwinds call into question one of the holy trinity, stocks can be very quick to fall in an environment where investors are jittery and desperate to own things that are steady and won’t get disrupted.

As an example, we were able to buy Facebook [FB] because of concerns that privacy restrictions and regulation would impair its business model. We don’t think they will. We were able to buy Dentsply Sirona [XRAY], the leading player in the dental-products industry, when growth wavered due to what we believe are fixable merger integration issues from putting Dentsply and Sirona together. Speedbumps always cause people to dump stocks, but I’d argue that’s more pronounced than ever today.

It took you until this year’s second quarter to invest in Wells Fargo [WFC], which hasn’t exactly been firing on all cylinders for some time. Why did it start to make sense then?

DO: We’ve followed Wells Fargo to greater and lesser degrees over the years. We looked closely at it last year when the stock was in the low-$50s, attracted by its leading deposit franchise, great profitability and strong balance sheet. It also had a number of company-specific problems and management upheaval that we thought were being addressed. But in the end we concluded the price wasn’t interesting enough so we moved on.

ON BANKS:

Despite the market hating them with such a passion, we still think banks are good businesses over time.

The drumbeat of bad news kind of continued. To score points with her base, Elizabeth Warren attacked Wells on a continual basis from the campaign trail. They went through another CEO. Interest rates started going down again. The market seemed to sort of throw up its hands and we ended up buying the stock at around $45 or so.

Despite the market hating them with such a passion, we still think banks are good businesses over time. Even in this interest-rate-suppression era, many of them are still nicely profitable and they are so capital-rich that they can return massive amounts of capital to shareholders. Wells also has meaningful room for improvement in its cost structure. The cost/income ratio has bloated from the mid-50s to the mid-60s, in large part because they’re throwing money at regulatory infrastructure. We don’t think that goes on forever and see no reason they can’t get back to a mid-50s cost/income ratio. That’s a huge source of potential return.

You’re not worried about lasting damage to the franchise from all the critical news?

DO: We think the reality is that most Wells Fargo clients are not closely following the latest news on Wells Fargo. Given how much attention we pay to it, I think investors can overemphasize that sort of headline stuff. Most people aren’t glued to a Bloomberg terminal all day and don’t read The New York Times and The Wall Street Journal. Another point I’d make is that there were banks in the aftermath of the financial crisis that had much worse reputational issues that have recovered.

If well managed, I’d expect Wells to similarly recover. And, by the way, if you look at the account trends and activity, there are signs of stability and improvement. The difficulties have gone on long enough now that you’d likely see some impact by now if there were going to be any. [Note: As low as $43 in August, WFC shares, somewhat buoyed by the naming of Charles Scharf as CEO on September 27, now trade at $50.75.]

Defense contractors have mostly been in favor of late. What made BAE Systems [London: BA] interesting to you earlier this year?

DO: Defense companies in general have been highly rated by the market, but when we established our position in BAE in the first quarter we were buying in at 11-12x earnings, almost half the level of many peers. Part of that reflected fear that the political upheaval in the U.K. might translate into the Labour party taking on a bigger role, and it has historically not been friendly to defense contractors. There was also specific concern over the company’s business with Saudi Arabia, which accounts for 10% or so of profits. The Saudi business is handled through a consortium of European companies and some countries, notably Germany, have called for a ban on selling military hardware to the Saudis. The situation is obviously very fluid, but our view was and is that the valuation discount on the shares was too high relative to the actual threat of lost business. [Note: At a three-year low of £4.40 in May, BAE shares currently recently traded at £5.70.]

You’ve shown no enthusiasm for low valuations in the automotive industry. Why?

DO: It’s never been a great industry, plagued by chronic overcapacity, cost structures that are difficult to align with demand because of labor and political challenges, and overdependence on easy credit. Volumes don’t grow much over time so it’s always a fight for share.

ON THE AUTO INDUSTRY:

It's never been a great industry and it's undergoing a great deal of change, which is arguably making it worse.

The industry is undergoing a great deal of change, which is arguably making it even worse. The transition to more hybrid cars, to more all-electric cars and to autonomous driving requires enormous capital spending and it’s difficult for us to see any of those as being positive for the industry. What Volkswagen has committed to invest over the next several years relative to its market cap is simply mind-boggling. And it’s all with uncertain return. As one auto-industry CEO explained to me, if he were launching a new diesel or gasoline model, he’d have a fairly good ability to forecast the demand for that model. With a hybrid or electric car, which might be highly dependent on governmental subsidies, forecasting is just much more difficult. It’s hard to get very excited about any of that.

The list of other things you aren’t particularly excited about would appear to include emerging markets, Japan and energy stocks. Can you briefly explain why in each case?

DO: There are exceptions like Samsung Electronics [Seoul: 005930], which we’ll discuss later, but we just struggle in emerging markets to find high enough quality businesses with sufficiently shareholder-oriented management teams. I don’t think emerging markets are ever going to have a starring role in this portfolio.

Japan is just terrible all around. The economy is terrible and most of the companies are terrible. They don’t care about shareholders. They aren’t transparent and disclosure is inadequate. You can sit in a meeting for an hour talking to the CEO through a translator, scraping for good information. At the end of the meeting he’ll say goodbye to you in perfect English and you really just want to bang your head against the wall. We recently had a failed investment there – Yahoo Japan – and it was a good reminder why we are so cautious about getting involved in Japan. Because of the disclosure barriers, we misunderstood the margin structure and a number of their re-investment requirements and it bit us pretty hard in the end.

With energy, I’ll tell you about another unsuccessful investment that explains quite well why I don’t generally invest in the sector. We still own a position in Imperial Oil [IMO], which is Exxon Mobil’s Canadian operation. We bought it because the company was supposedly coming to the end of a heavy tar-sands investment cycle, which offered the prospect of significant, long-lived and cash-generative production coming online.

Expectations, however, ran into the reality of the energy business. They’ve had never-ending production problems that have required additional capital to fix. The production there is has been less efficient than expected. There are transportation bottlenecks in Canada, and there are political issues in resolving those. It’s just a difficult environment in which to invest.

Turning to environments that you're finding more amenable, describe your investment case for online travel agency Booking Holdings [BKNG].

DO: What often happens in our research process is that we will do some work on a company and though we may fundamentally like the business, we think the valuation is unattractive. We’ll keep watching it and if the stock price goes down enough to make the valuation interesting, we’re ready to act.

That’s basically what happened with Booking. We did a considerable amount of research on the online travel agent (OTA) industry, focused on Booking and Expedia [EXPE], and while we concluded Booking was the better business, we ended up only buying into Expedia at the time. But as Booking’s share price continued to lag behind, we were able to buy at what we considered an attractive price in the second quarter.

The online travel agent industry is an attractive one. Travel generally grows faster than GDP and because more people are booking their hotels and airlines online, OTAs will grow faster than the travel market. Operating margins are high, free-cash-flow generation is high, and the business should produce high-single-digit to low-double-digit revenue growth for a long period of time.

So why were we able to buy the stock at 13x unlevered earnings, net of cash? The simple answer is that the business slowed down, primarily due to a relatively weak travel market in Europe, where Booking is very well established. In addition, the company has been investing in brand marketing to drive more direct traffic to its sites and save on some of the expense of buying Google keywords to generate traffic. That has dampened operating margins slightly, but we ultimately think it’s the right strategy and direct traffic is starting to grow faster than that generated through Google. In any event, evidence of even a little pressure on revenue growth and operating margins seemed to shake out a lot of the momentum and growth investors, which ended up giving us the opportunity.

In what ways is Booking a better business than Expedia?

DO: Again, we like both of them, but the main difference is that Expedia is more of a U.S. business and Booking is more an international one. The hotel industry in the U.S. is far more consolidated than it is outside the U.S., with the result that non-U.S. hotels rely more heavily on online travel agents because smaller players have fewer resources and less name recognition to drive direct business. That translates to commission structures, which are more attractive outside the U.S. than inside, which incrementally benefits Booking. Also, Booking has frankly so far been a better-run company, which has shown up in higher growth and profitability relative to Expedia.

How do you assess the risk of hotels overall trying to wean themselves off OTAs?

DO: Hotels definitely prefer if you book directly rather than booking through an OTA, where they have to pay a 10%-plus commission. That said, that’s only realistic for the very largest hotel companies in the world with strong brand recognition and for when people have a strong preference for where they want to stay. Most people don’t travel that much and don’t know the hotel they want. They want to see choices, which an OTA gives them. We think that will keep OTAs highly relevant.

Do you worry about Google getting more directly involved in selling travel?

DO: We do. It is a risk and something we watch and think about. But being an OTA is very different from what Google is. You have to have people calling on hotels and airlines. You have to negotiate capacity allocations. You have to negotiate commissions. It’s a sales-intensive business rather than a purely digital one. Which isn’t to say Google can’t skim some off the top, but we think the OTAs have a different business model and have a competitive advantage.

How are you looking at upside in the stock from today’s $1,945 price?

DO: This is one where we don’t think we need to build a 40,000-page spreadsheet to make a judgement. We think revenue can grow sustainably at 5-10% per year. The margin structure is positive and the company is using its prodigious free cash flow to buy back up to 25% of the outstanding shares. That should produce low-teens or better annual growth in earnings per share. You also have a net cash balance sheet.

We look at that and believe the business should be worth at least 20-22x unlevered earnings, which is a pretty steep discount to where it’s traded in the past. If we put that multiple on our earnings estimates a couple years out and discount it back to today, we think the fair share value now is in the $2,500 range. As is typically the case, we would expect to benefit both from the discount to value closing and the value continuing to grow nicely over time.

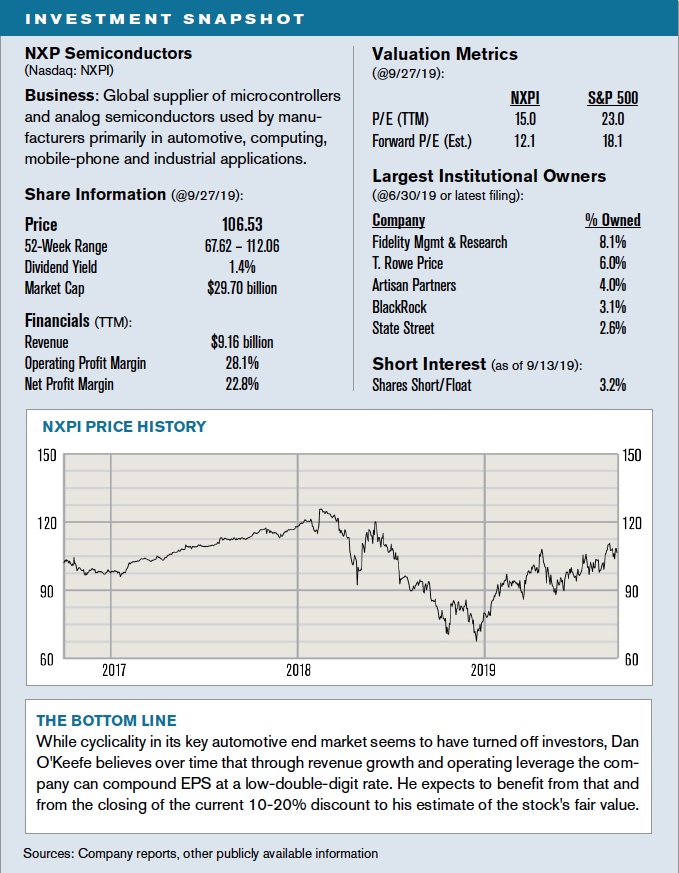

NXP Semiconductors [NXPI] would be another high flyer that in the past year came somewhat back to earth. Why are you bullish on its prospects?

DO: We bought the stock a year ago after the merger deal with Qualcomm fell apart. The deal had valued NXP at $120 per share and the stock price fell into the low-$90s, which is around where we first bought in. The shares fell further from there as concern over a cyclical slowdown in the global auto industry – where NXP is the leading semiconductor and microcontroller supplier – started to intensify. Back to the holy trinity I spoke about earlier: Oh my God, are you telling me this is subject to cyclicality and may not grow no matter what?

Automotive end markets account for about half of the overall business, with much of the rest consisting of selling industrial microcontrollers for a variety of applications and selling semiconductor components that go into mobile phones. All of the end markets have attractive growth prospects, but the auto business will be the biggest driver. Given the ongoing electronification of cars – which only intensifies as more autonomous-driving functionality rolls out – auto semiconductors will grow at a rate significantly higher than auto production. We expect NXP’s automotive business to grow at something close to a 10% annual rate.

Short-term, we estimate overall revenue will decline 5-6% this year as a result of the automotive market taking a cyclical hit. Going into the downturn inventories are depleted as automakers scale back production, but that will snap back as production picks up and inventories in the factories are replenished. But long-term, again, it’s hard to imagine autos not having far more semiconductor content than they do right now.

Did the company get off track at all through the drawn-out Qualcomm deal process?

DO: There was that concern and it probably contributed to the stock getting as cheap as it did, but we have not seen any evidence of it. Operating margins are in the mid-20s and the business produces prodigious free cash flow, 100% of which the company has committed to returning to shareholders through buybacks and dividends. It was and is a very well-run company.

Now at $106.50, what do you believe the shares are more reasonably worth?

DO: We factor in the cyclical downturn in 2019 and then gradually normalize revenue growth and earnings over the next couple of years. We assume high-single-digit revenue growth coming out of the trough and margins scaling with the revenues to come in higher than they were in 2018. Applying what we consider to be a conservative 16-17x unlevered earnings multiple to our estimates two to three years out, and then discounting that back to today gives us a share price in the $120 to $130 range.

With the revenue growth and operating leverage we estimate, EPS would compound at a low-double-digit rate over time. We’d expect value to compound commensurately.

You mentioned earlier the potential you see in banks. Why is Citigroup [C] a good way to play that?

DO: Citi very much fits the profile of what we’re finding attractive in the sector. It’s roughly half a consumer bank and roughly half a corporate bank. The consumer bank is focused on credit cards, where it’s the #1 global card issuer by loan balances, with the rest broadly diversified in retail banking across a number of geographies, primarily the U.S., Latin America and Asia Pacific.

The corporate side of the bank, called the Institutional Clients Group, is primarily involved in things like treasury, trade finance, security services and foreign exchange. These tend to be flow businesses that are pretty deeply integrated into the day-to-day activities of their corporate clients. I won’t say they’re recession-proof, but they are recurring and ingrained activities which make them somewhat more stable and valuable.

Overall, a bit less than half of the business is in North America, with 15% or so each coming from Europe, Latin America and Asia. We think the diversification of the business mix by geography and otherwise is quite attractive.

How would you characterize Citi's sensitivity to interest-rate levels?

DO: The business is not that interest-rate sensitive. Credit-card books of business are far less sensitive to interest rates than are other commercial or retail loans. On the institutional side, as I mentioned, much of the revenue is flow related rather than balance-sheet related. A 25-basis-point cut in the federal funds rate translates overall into about a $50 million quarterly revenue decline. That’s basically irrelevant on a revenue base of $19 billion.

Describe the capital-return part of the thesis here.

DO: Over three years ending in mid-2020, Citigroup will have returned more than $60 billion in capital to shareholders, primarily in the form of stock buybacks, but also dividends. That’s on a market cap of about $160 billion. Other banks are returning similar levels of capital relative to market cap. We can’t think of a similar example in our careers of an industry or company returning this much capital relative to market value. And that won’t be the end of it. We expect Citi to continue with attractive capital returns through the next Comprehensive Capital Analysis and Review.

How cheap do you consider the shares at today’s $69.50 price?

DO: For a diversified global consumer and corporate bank you’re today paying roughly 9x current-year earnings. That’s assuming a 12% return on tangible equity. The company’s cost/income ratio has fallen for 11 quarters in a row and management is targeting a 13.5% return on tangible equity by 2020. If they hit that, and we think they can, the P/E at today’s stock price is around 7.5x.

Our view is that this business is worth closer to 12x earnings. If they hit their return-on-equity targets and the market recognizes it, on top of the dividends earned the stock would be roughly 50% higher than it is today.

Returning to another global technology business, what’s behind your interest in Samsung?

DO: Samsung is a leader in smartphones, semiconductors and other electronic components, with global scale and vertical integration in key businesses that provide it with competitive advantage.

While people know the company maybe more for its cellphones, our interest revolves around its memory-semiconductor business. Samsung is the leading global manufacturer of DRAM semiconductors with a roughly 50% share, in a consolidated industry where two competitors, SK Hynix [Seoul: 000660] and Micron Technology [MU], split most of the rest of the market. Samsung is the technology and cost leader and by far the best operator.

The long-term demand picture for the company’s semiconductors is very good. Demand – in key areas such as data centers, mobile technology, personal computers and a variety of automotive and industrial applications – is driven by increasing need for memory in all kinds of products.

What’s made the stock interesting is the market’s reaction to the memory- semiconductor cycle. The business is less cyclical than it used to be as the industry has consolidated and become more rational, but it’s still prone to ups and downs. This year we’ve seen a big price drop in DRAM, a function of some slowdown in mobile demand and of the aftermath of significant buying for inventory in the datacenter market in 2018. Though volumes this year are still up nicely, pricing is down a lot and Samsung’s semiconductor EBIT is likely to be more than cut in half. Semiconductors will still account for 50% of overall EBIT, but are typically closer to 75% of the total on a normalized basis.

So you have a cyclical downturn, but an attractive long-term demand outlook. It’s in a highly consolidated industry. We don’t see any major threats of technology disintermediation. Even at the trough of the cycle the company is nicely profitable and generating cash. Combine that with a low multiple on current earnings and a very low multiple on a reasonable estimate of more normalized earnings, and we think that lines up in our favor.

You’re generally not a fan of corporate governance in emerging markets. How do rate Samsung on that front?

DO: Poorly. There’s a complex cross-holding structure that allows the family to control the company with a small economic stake. J.Y. Lee, the vice chairman and the son of the founder, has spent time in jail for bribing South Korea’s president and recent headlines indicate he may have to go back again. They should also return far more capital to shareholders, given that net cash and investments on the balance sheet are 30% of the company’s current ₩315 trillion market cap.

On the other hand, we’ve owned the stock since late 2013 and governance has actually improved a bit. At least it’s moving in the right direction, albeit more slowly than it should. And importantly, the company is very well run. We discount the valuation because of the governance issues, but they don’t keep us from owning the stock.

How attractive are the shares at today’s price of ₩48,500?

DO: The enterprise value today is roughly ₩235 trillion, which is about 8x our current-year estimate of EBIT and about 5x our estimate of normalized EBIT two years out. At a 9x EV/EBIT multiple on our 2021 numbers, discounted to today, the stock would trade at ₩70,000. That works out to about 11x normal unlevered earnings. That’s a pretty cheap multiple for a business like this.

Speaking broadly again, what impacts do you see from the continued rise of passive and algorithmic investing?

DO: It’s made the market much more momentum-oriented. People pile into ETFs and indexes that have been working and that money just chases the winners, or vice versa. A few weeks ago when the market panicked about falling interest rates, all of my U.S. financials were at one point trading down 2.49%. All of them. This is not price discovery. This is a wave of money flushing out of some financials ETF.

We're just going to do what we we’ve always done. We’re looking for businesses that meet certain quality criteria when they’re trading at attractive prices. Over time we believe that will work as it historically has.

You have an undergraduate degree in philosophy from Northwestern. With the benefit of hindsight, are you a strong advocate for a liberal arts education?

DO: I am a very strong advocate for a liberal arts education. In almost any profession – especially a competitive, analytically driven and communication-driven business like this one – your primary competitive advantage is how well you can think, how well you can analyze, how well you can organize information, and how well you can communicate that information. The way you get proficient at all those things is by reading and writing, and reading and writing, and reading and writing. You study a number of different things and learn how to look at them from different angles. All of that traces back to education in the liberal arts.

ON INVESTOR TRAINING:

The way you get proficient at what's important in this industry is by reading and writing and reading and writing.

That’s not an excuse for not learning about business, economics, accounting and finance. If I were to fashion an ideal candidate, it would be someone who double-majored in something like History and something like Economics, with enough practical exposure to the world of business and markets to know that they love all that stuff.

I was a 50% failure with respect to my ideal model. I took only one Economics class and didn’t have that much exposure to the world of business. But I stumbled into a job at Morningstar as a mutual-fund analyst and just fell in love with it all. I look back on it and can’t imagine a 24-year-old me interviewing me today – what a joke! But that’s how I caught the bug – it turned out to be a perfect way to get started.

---------------------------------------

If you enjoyed this article, we invite you to register for a free trial so that you can further evaluate the many ways a subscription to Value Investor Insight can benefit you. There is no obligation and no payment required. To register, click here.